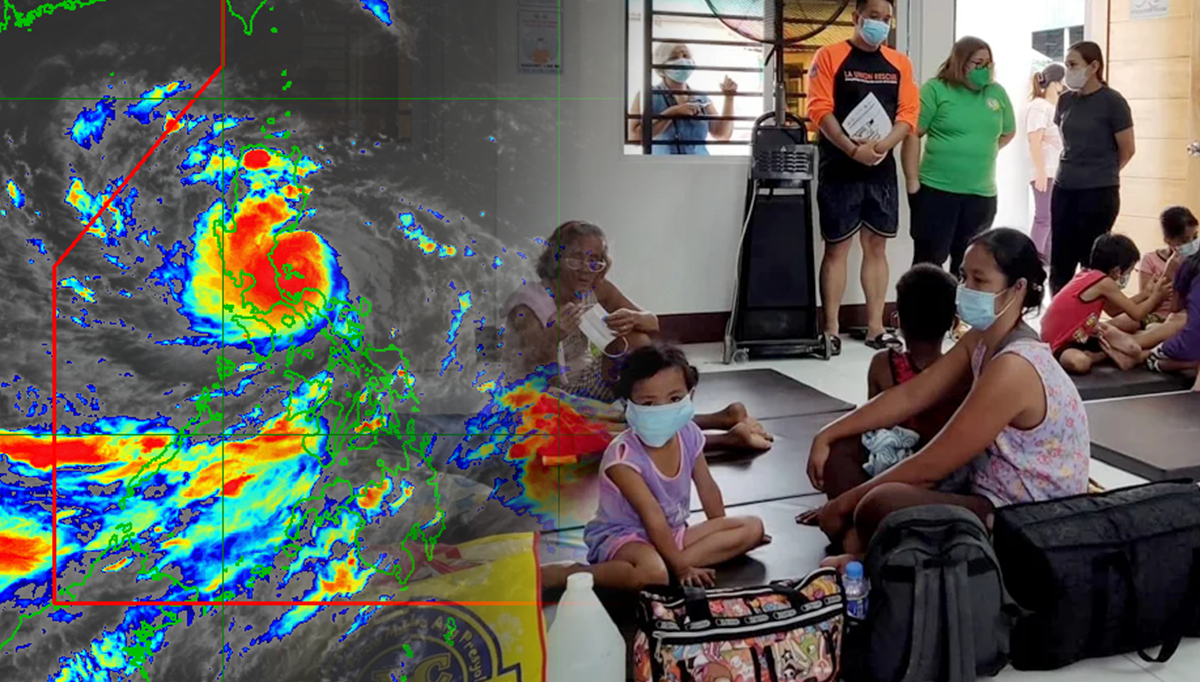

PHOTO LA UNION PROVINCIAL GOV’T/DOST-PAGASA

MANILA, Philippines—Over a million individuals were on the path of Super Typhoon Karding as it ravaged Luzon last month. Among those who suffered most were children who are being exposed to far more dangerous situations.

According to estimates by the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), a total of 1,072,282 individuals—or 299,127 families—felt the impact of Karding (international name: Noru), which wreaked havoc in Luzon.

According to the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA), which monitored the impact of Karding on poor communities in the Philippines, out of the total 689,000 people in vulnerable populations hit by Karding, 223,236 were children below age 15.

READ: Karding batters 600,000 people living below poverty line

The United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) said the typhoon exposed Filipino children to various dangers involving their health and wellbeing. It also halted many students’ progress in catching up with learning losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Children’s health at risk

According to Unicef, “damaged health, water, and sanitation facilities and disrupted services increase the risk of getting sick from many diseases.”

Last week, acting Health Secretary Maria Rosario Vergeire reported that at least 21 health facilities had been damaged at the height of Karding.

READ: DOH reports damage to some health facilities in Nueva Ecija due to Karding

However, she emphasized that the damage was minimal and no COVID vaccine had been destroyed as many feared.

READ: No COVID vaccine wastage due to Karding — DOH

Data from NDRRMC showed that 58,944 houses were damaged.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

In 2021, after Typhoon Odette slammed into parts of Bohol and Cebu, some Unicef Philippines staffers who traveled in the areas noted that among the major concerns that needed to be addressed in the aftermath of the typhoon was access to safe water supply.

“Lack of safe drinking water can lead to dehydration, and inadequate sanitation and hygiene can lead to the spread of water-borne diseases like diarrhea, a leading cause of death among children under five years of age,” said Sol Balane, Unicef WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) consultant.

Unicef also pointed out that the lack of safe water and nutritious food can lead to malnutrition and even death.

Latest data from the Department of Agriculture (DA) showed that agricultural losses due to Karding rose to P3.12 billion as of Oct. 3. This included 158,117 metric tons (MT) of products on 170,762 hectares (ha) of cropland in the Cordillera Administrative Region, Ilocos Region, Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon, Calabarzon (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon), Bicol Region, and Western Visayas.

The DA said rice, corn, cassava, abaca, high-value crops, livestock, poultry, and fisheries products had been destroyed. Agricultural infrastructure also took a hit, the DA added.

READ: Karding’s damage to PH agriculture tops P3 billion

The NDRRMC noted in its situation report that as of Oct. 3, a total of 24,312 family food packs had already been distributed in areas hit by Karding.

Learning interrupted

The Department of Education (DepEd) earlier said that 12,174,549 students in 21,509 schools were displaced by Karding for mainly two reasons—their classrooms were damaged or used as evacuation centers.

As of Sept. 30, the DepEd said the cost of repair and reconstruction of 165 schools damaged or destroyed by the typhoon—including 386 classrooms—was already pegged at P1.17 billion.

The schools which suffered infrastructure damage were located in the Cordillera, Ilocos Region, Cagayan Valley, Central Luzon, Bicol Region, and the National Capital Region.

READ: DepEd needs P 1.17B to fix schools hit by Karding

Out of the 561 schools converted into shelters, 92 still housed evacuees as of Oct. 1.

“Schools are often used as evacuation centers before, during, and after emergencies, preventing children from attending their classes and catching up on lost learning during the pandemic,” Unicef said.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

According to DepEd spokesperson Michael Poa, the usual protocol for schools that suffered damage was for them to switch to either distance or blended learning.

“If this is not possible, what we are doing now is coordinating with various local governments to see if they have temporary spaces like covered courts and other rooms, which they can lend to us to hold classes for our learners,” he said.

Disasters and children’s mental health

Disasters, like super typhoons, have an impact on children’s mental health.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), children may experience anxiety, fear, sadness, sleep disruption, distressing dreams, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and anger outbursts following a disaster.

Children under the age of 8, the US CDC said, are at particular risk for mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after a disaster.

One study published in the peer-reviewed journal Pediatric Medicine titled “Children’smental health at times of disasters: a narrative review” found that disasters often lead to the most traumatic events among children.

The death of a parent or another family member, the loss of home and belongings, and various abuse to children due to uncertainty about basic needs and the future were among the traumatic impacts of disasters on children.

“Intolerance of the uncertainty associated with a disaster leads to anxiety, fear, and worry for both adults and children. Repetition of a displacement makes a child even more vulnerable to psychological trauma,” the study noted.

The study also found that some children may experience Acute Stress Disorder, which involves specific fear behaviors that could last from three days to a month after a traumatic event. The symptoms may include sleep disorders, negative affect, hyper-vigilance, or complaints of physical symptoms such as headache or dizziness.

Children with prior mental health diagnoses—such as depression, anxiety, or ADHD—may also demonstrate more symptoms after a disaster.

“The symptoms that children manifest in the immediate aftermath of a disaster will vary according to their ages and developmental stages,” the study said.

Children’s mental health at times of disasters: a narrative review

Stress and emotional problems may affect children’s physical health, quality of life, and how they do at home, in school, and in their communities.

“It is important to keep children mentally and physically safe both during and after a disaster. Parents who are able to recognize the signs of children’s mental stress can best help their children cope and remain healthy,” US CDC said.

Children vulnerable to abuse, violence

Aside from disasters’ impact on children’s mental health, Unicef noted that “the loss of income and heightened stress among families and communities increase the risk of violence, abuse, and exploitation.”

A separate study funded by The Philippines Project—a policy-engaged initiative to stimulate research collaboration between academics and policymakers in the Philippines—based at the College of Asia and the Pacific of The Australian National University (ANU) found the impact of multiple natural disasters on Filipino children.

In the study, “The influence of natural disasters on violence, mental health, food insecurity, and stunting in the Philippines: Findings from a nationally representative cohort,” researchers saw that natural disasters are associated with child physical abuse and family violence.

Results from the survey the researchers conducted from October 2016 to January 2017 among over 4,000 Filipino children found that at least 41 percent of children affected by natural disasters in the past 12 months were living in households that experienced family violence.

At least 33 percent of children reported witnessing violence following a disaster, while one in three children—30 percent—reported being physically hurt by a parent, and 20 percent said being hurt by parents in a forceful manner.

One in three children (35 percent) were stunted—or were too small for their age.

READ: As vaccination rates plummet, children face bigger monster—wasting

Bearing the brunt of climate change

Civil engineer and wind dynamics expert Joshua C. Agar—an engineering faculty member at the University of the Philippines–Diliman—had told INQUIRER.net that the country was likely to see stronger typhoons due to climate change.

“Expect typhoons like Karding that are small in size but with super destructive winds near the eye,” he said.

READ: More powerful typhoons looming due to climate change, says wind dynamics expert

This was echoed by Albay Rep. Joey Salceda, who said that “one of the effects of climate change is that the storms are growing stronger. The Philippines will bear the brunt of such extreme events in the Pacific. Karding will not be the last super typhoon, and it might not even be the last just this year.”

“The Eastern Seaboard, which tends to get hit by extreme weather events, also tends to have poorer provinces. Relying on local resources or mere coordination by the national government will not be enough,” he said.

“The local resources are simply not enough. And in extreme events such as super typhoons, the local responders are also victims, and their institutions are also disrupted,” Salceda added.

READ: Karding’s onslaught highlights urgent need for disaster agency — Salceda

Climate change, Unicef said, is a child’s rights crisis.

The Philippines is the fourth most vulnerable country to climate change, according to Pacific Disaster Center and UN Humanitarian Country Team. With that in mind, Unicef noted that “children are bearing the brunt of climate change, yet they are the least responsible for it.”

“Climate action should put children at its center,” Unicef added.

Among the urgent action that Unicef said was needed to provide a better future for Filipino children include:

- Protect and ensure essential social services for children.

- Equip children with the knowledge and ability to adapt to a climate-changed world.

- Increase funding and investments in adaptation areas such as climate monitoring, analysis, and forecasting systems .

In 2021, a preprint study by The Lancet, a highly-respected peer review science and health journal, surveyed 15,543 children aged 16-25 years old from 10 countries, including the Philippines, United Kingdom (UK), Finland, France, United States (US), Australia, Portugal, Brazil, India, and Nigeria.

Results showed that most of the respondents reported a significant amount of worry. Over 60 percent said they felt very worried (32 percent) or extremely worried (27 percent) about climate change.

At least 25 percent felt moderately worried, 11 percent were a little worried, while five percent said they were not concerned about climate change.

The countries where most respondents felt “very worried” and “extremely worried” were countries that suffer severe impacts of climate change, including:

- Philippines: 84 percent (49 extremely worried, 35 very worried)

- India: 68 percent (35 extremely worried, 33 very worried)

- Brazil: 67 percent (29 extremely worried, 38 very worried)

Most of the respondents also associated negative emotions with the climate crisis—including “sad,” “afraid,” “anxious,” and “powerless.”

READ: ‘Eco-anxiety’: PH children among most stressed by climate crisis

A separate study published in Science Magazine—the peer-reviewed academic journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)—found that newborns across the globe—including children to be born a few years from now—will face disproportionate increases in extreme weather events that would include heatwaves, droughts, crop failures, river flooding, and wildfires.

Children from low-income countries would be more exposed to future harsher events caused by climate change.