Remembering martial law: Hope, then despair

MANILA, Philippines—When Ferdinand Marcos was president, one thing that activist Judy Taguiwalo clearly remembered was how glaring the gap between rich and poor had become.

“I was a UP student from 1965 until I graduated in 1970,” Taguiwalo said, recalling her campus days as a student from Negros Occidental.

She recalled learning in UP “inside and outside the classroom.”

The UP Student Council encouraged students to join a program to learn from people. “We would go to poor communities and talk to people about their lives,” Taguiwalo told INQUIRER.net.

This brought Taguiwalo up close with poverty and the inequality which she would shortly discover was the root cause of people remaining poor despite working hard. What made the people poor, Taguiwalo would realize, was not idleness as wrongly reinforced by the fictional character “Juan Tamad.”

Article continues after this advertisementHer life of commitment and service, however, did not sit well with authorities at the time. Martial law was declared on Sept. 23, 1972 by Marcos to quell what he then said was growing threats from Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF).

Article continues after this advertisementThe CPP was waging a socialist revolution while MNLF was waging a separatist war.

During a crackdown on perceived government enemies months after martial law had been declared, Taguiwalo was arrested on July 1, 1973. She was again arrested on Jan. 28, 1984. In both cases, she had been charged with subversion and tortured by her captors.

Marcos dictatorship

Marcos had been elected president in 1965 and won reelection in 1969 which gave him eight years in power that was supposed to end in 1973, an election year, as mandated by the 1935 Constitution. That constitution presented itself as the biggest obstacle to a third term for Marcos.

Tillman Durdin, a New York Times correspondent, said in his article “The Philippines: Martial Law, Marcos-Style” that Marcos proved that “once dictators consolidate power, they can usually be assured of long, often lifetime, tenure of office.” From 1965 to 1986—a total of 21 years—Marcos kept a tight grip on the presidency.

As stressed by David Wurfel, a political science expert, initially it looked like Marcos was content with staying on as president through a new Constitution, the one framed by a constitutional convention that Marcos maneuvered to happen but which Wurfel said was filled with delegates who were allies of Marcos.

The Official Gazette stated that “the facts are clear”—a week before the declaration of martial law, a number of people had already received information that Marcos had drawn up a plan to completely take over the government and gain absolute rule. Then Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr. exposed it in a Sept. 13, 1972 privilege speech.

Aquino said he had received a top-secret military plan given by Marcos himself to place Metro Manila and outlying provinces in the control of the Philippine Constabulary as a prelude to martial law and that he was going to use a series of bombings in Metro Manila, including the 1971 Plaza Miranda bombing, as justification.

Juan Ponce Enrile, then Marcos’ justice minister, had recalled in his memoir that on a late afternoon in December 1969, he was instructed to look at the powers of the President as Commander-in-Chief as stated in the provisions of the 1935 Constitution.

Marcos made this instruction as he “[foresaw] an escalation of violence and disorder in the country and [wanted] to know the extent of his powers as commander-in-chief.” The late dictator also stressed that “the study must be done discreetly and confidentially.”

The Official Gazette stated that on Sept. 21, 1972, “democracy was still functioning in the Philippines” as Aquino was still able to deliver a privilege speech. Then a protest march at the Plaza Miranda was attended by a crowd of 30,000 and received coverage from newspapers, radio, and television.

But in the evening of the next day, the pretext of martial law was provided with the alleged ambush on the convoy of Enrile, then the powerful defense minister, as he was on his way home to Dasmariñas Village in Makati. This ambush, as Enrile later revealed in 1986, was staged by Marcos to justify the declaration of martial law.

The anniversary of the declaration of martial law is traditionally commemorated every Sept. 21, but its actual declaration was on Sept. 23, 1972, as stated by the Official Gazette, saying Proclamation No. 1081, the legal document issued by Marcos to declare martial law, had been antedated.

READ: Countdown to 50th anniversary of martial law launched

Red-bait

When Marcos declared martial law, one of his main reasons was to stamp out rebellion by communists, especially New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of CPP, which Marcos said had 1,028 “armed regulars”. In the crackdown on communist rebellion, Wurfel said thousands were imprisoned on suspicion of complicity or sympathy with the NPA.

The New York-based Amnesty International (AI) said the nine-year martial law “unleashed a wave of crimes under international law and grave human rights violations, including tens of thousands of people arbitrarily arrested and detained, tortured, forcibly disappeared, and killed.”

Based on Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission (HRVVMC) data, 11,103 individuals had fallen victims to human rights violations by the dictatorship.

This count, however, covered only those with approved claims for compensation from the Human Rights Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013.

AI said that from 1972 to 1981, and in the remainder of the 20-year regime of Marcos, 70,000 people were imprisoned, 3,257 were killed and 34,000 were tortured, while the Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance said 878 went missing.

READ: #Edsa36: Remembering those who gave up their lives

According to AI, it had documented “extensive human rights violations which clearly showed a pattern of widespread arrests and detention, enforced disappearances, killings and torture of people that were critical of the government or perceived as political opposition”.

READ: The enduring trauma of martial law

Those arrested, it said, included church workers, human rights activists, lawyers, unionists and journalists. It also documented a pattern of torture in interviews with prisoners from that time. In 1981, the organization released a research on enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions that took place from 1976.

Taguiwalo was one of those who suffered at the hands of the dictatorship and became one of its most prominent survivors.

She was only 22 years old when she was first arrested. She said she was interrogated for two straight nights in Iloilo City and was made to lie naked while state agents poured water into her nose.

Even after her release in 1974, Taguiwalo continued her work as part of the underground resistance: “That was my life and the life of the hundreds of youths who decided to fight the dictatorship.”

She was again arrested in 1984 and released only in 1986, when Marcos was ousted by the 1986 People Power Revolution.

The second time she was arrested, Taguiwalo was pregnant. She was brought to Camp Olivas in San Fernando, Pampanga, where she was “psychologically tortured”—forced to listen and read narratives about people who were killed or made to disappear because they refused to cooperate with state agents.

Martial law documents

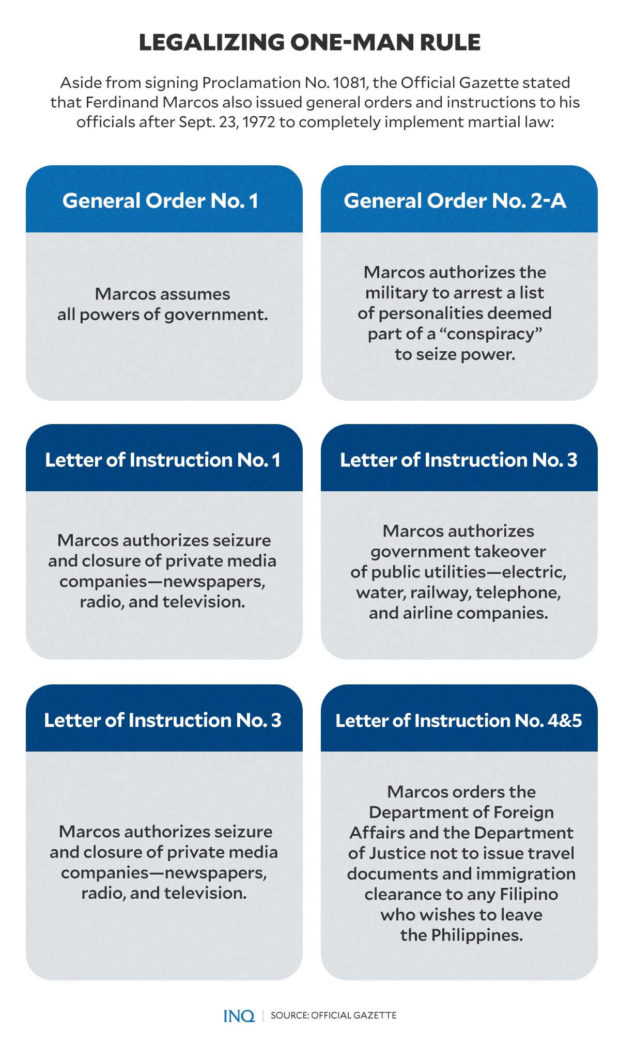

Aside from signing Proclamation No. 1081, the Official Gazette stated that Marcos also issued general orders and instructions to his officials after Sept. 23, 1972 to make his actions legal. Among these were:

- General Order No. 1: Marcos assumes all powers of government.

- General Order No. 2-A: Marcos authorizes the military to arrest a list of personalities deemed part of a “conspiracy” to seize power.

- Letter of Instruction No. 1: Marcos authorizes the seizure and closure of private media companies—newspapers, radio, and television.

- Letter of Instruction No. 2: Marcos authorizes the takeover of public utilities—electric, water, railway, telephone, and airline companies.

- Letter of Instruction No. 3: Marcos orders the military to seize all privately owned aircraft and watercraft bearing Philippine registry.

- Letter of Instruction No. 4 and 5: Marcos orders the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Justice not to issue travel documents and immigration clearance to any Filipino who wishes to leave the Philippines.

The Official Gazette stated that all in one day—Sept. 23, 1972—seven primary English, one English-Filipino, three Filipino, one Spanish, and four Chinese dailies; 66 community newspapers; 11 English weekly magazines; seven television stations; and 292 radio stations were shut down.

The day martial law was declared, opposition senators Aquino, Jose Diokno, Ramon Mitra Jr., and Francisco Rodrigo were arrested. Journalists Teodoro Locsin Sr. of the Philippines Free Press, Chino Roces of Manila Times and journalists Amando Doronila, Luis Beltran, Maximo Soliven, Juan Mercado and Luis Mauricio were also arrested.

READ: Fast Facts: The Marcos martial law regime

Likewise, the HRVVMC said 579 businesses were “violently and illegally” taken over by the dictatorship. Marcos’ martial law would officially end on Jan. 13, 1981, but he would “reserve decree-making powers for himself” until his regime was officially ended by the bloodless revolution in 1986.

Economic costs

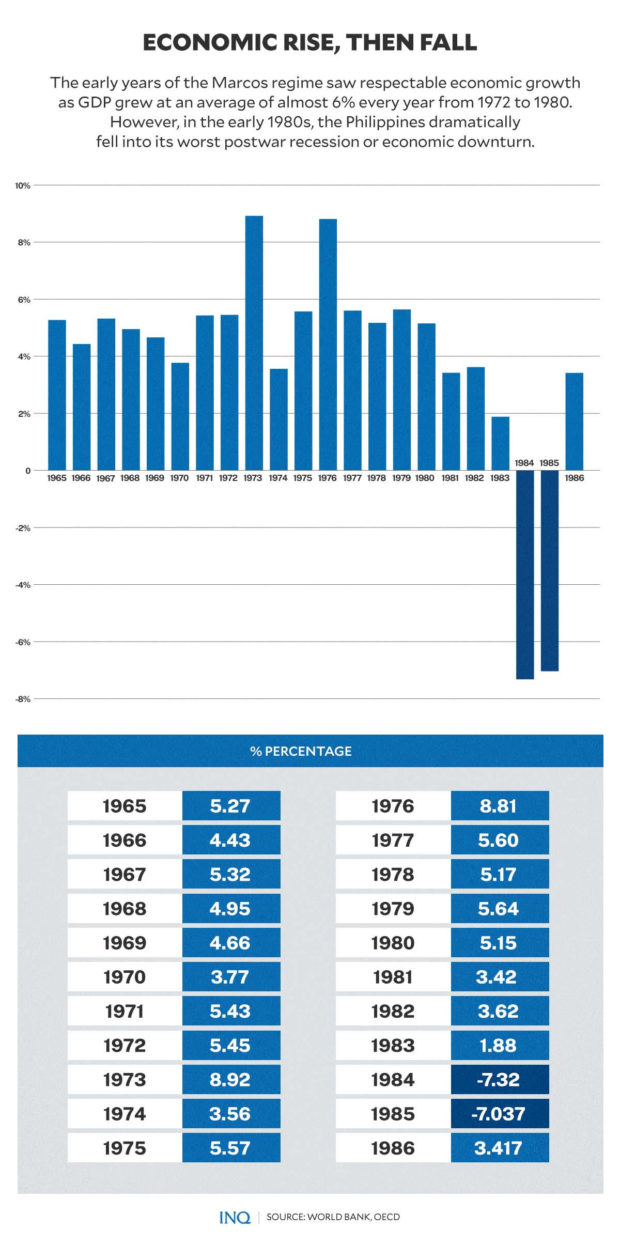

HRVVMC said the early years of the Marcos regime indeed saw respectable economic growth as gross domestic product (GDP)—which roughly measures a country’s total income—grew at an average of almost six percent every year from 1972 to 1980.

“This is good insofar as high economic growth is typically a necessary condition for achieving higher incomes and more jobs for the people,” it said.

However, in the early 1980s, the Philippines dramatically—but expectedly—fell into its worst postwar recession or economic downturn. GDP shrank by 7.3 percent for two consecutive years— 1984 and 1985. The last time an economic downturn of this magnitude happened was in World War II.

GDP for every person, which can be interpreted as the average income of the Filipino, also fell by 9.4 percent in those two years. So large was this downturn that it took the country more than two decades to recover the level of GDP for every person in 1982.

HRVVMC said the GDP for every person in 1982 was more than P48,000. This fell sharply because of the economic crisis in the regime’s waning years and did not recover until 2003. These so-called “lost decades of development” singularly demonstrate the pernicious impacts of the dictatorship on economic lives.

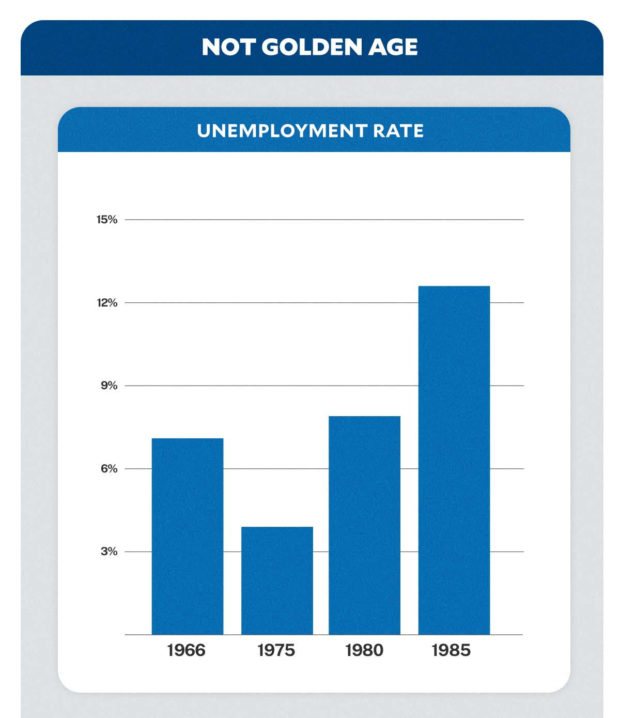

The think tank Ibon Foundation said the years 1975 to 1986 was actually a time of intense social crisis and economic difficulty for most Filipinos, stressing that the unemployment rate was falling in the early years of Marcos regime—from 7.1 percent in 1966 to 3.9 percent in 1975.

But this reversed in the mid-1970s to rapidly rise back to 7.9 percent in 1980. “The situation was worse in the 1981 to 1985 period: unemployment averaged nearly 11 percent, including a high of 12.6 percent in 1985,” Ibon Foundation stressed in 2016, the year Marcos was laid to rest at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

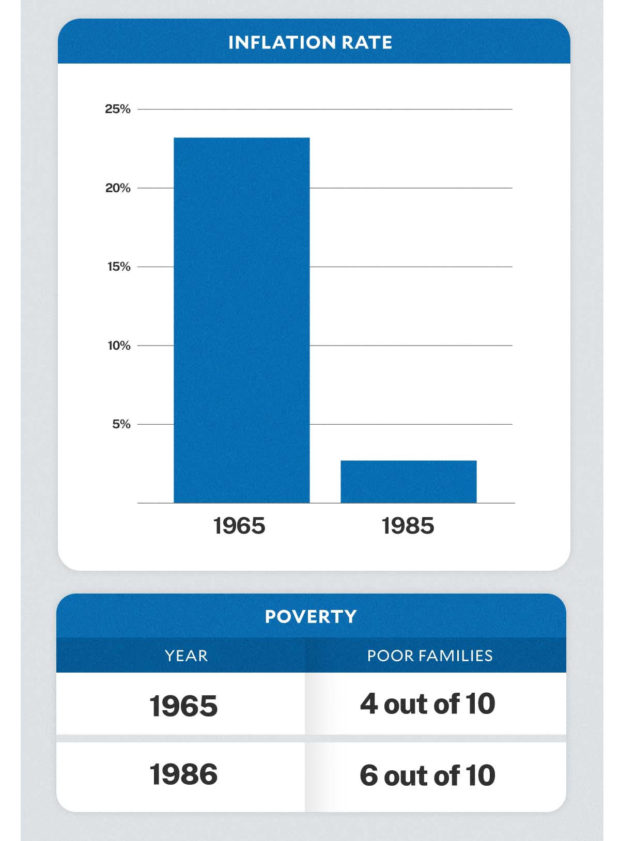

The Martial Law Museum stated that “poverty worsened” over the course of the dictatorship, emphasizing that six out of 10 families were poor by the time the Marcos regime ended, an increase from the four out of 10 families before he took office in 1965.

READ: Marcos’ martial law: Golden age for corruption, abuses

Taguiwalo told INQUIRER.net that it was not easy to forget the stark contrast between the “malnourished” children of the Negros islands while a rich and powerful family is able to deliver breastmilk by plane to its child.

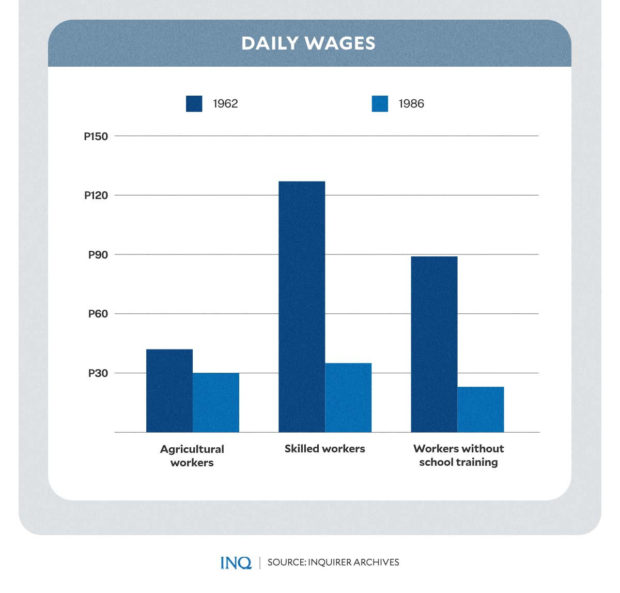

The daily income of agricultural workers at the time declined by at least 30 percent—from P42 in 1962 to P30 in 1986. The wages of farmers even went as low as P23 in 1974, right after the declaration of martial law. From P127 and P89 daily income for skilled workers and workers without school training in 1962, wages fell sharply to P35 and P23 in 1986.

These declines happened in the years when prices of goods were surging, especially in the last 10 years of the dictatorship: “We can see that prices of basic commodities tripled, such that what cost P100 in 1976 now cost more than P300—even nearing P400—in 1986.”

Continuing the struggle

Taguiwalo, who was freed from prison in 1986, when Marcos was ousted, decided to continue her struggle for “truth, democracy, and justice,” saying that “from the beginning, it was clear to me that we are not only fighting the dictatorship, we are fighting for a decent life for all.”

“We are fighting for social justice because since the start, there has been a stark contrast between the rich and the poor. I am from Negros Occidental. We do not own vast lands. I was only able to study at UP because I was a scholar,” Taguiwalo said.

“The intensification of poverty is not only an issue about the Marcoses against the Filipino people. Poverty is really systemic. So our efforts have been for civil and political rights, and even economic rights—jobs, decent wages, and land, especially for our farmers,” she said.

When Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., son of the late president, won the 2022 presidential elections, Taguiwalo said history had shown that resistance, activism or dissent would persist as long as their causes do—inequality and injustice.