A case study of Battered Wife Syndrome: The beating of Ana Jalandoni

STOCK PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines—The celebration of National Women’s Month in the month of March in the Philippines was shaken by a high-profile case of violence against women involving two celebrities—actress Ana Jalandoni and actor Kit Thompson.

The Philippines has been observing National Women’s Month as a way to celebrate, empower and defend the rights of women.

The high-profile case of Jalandoni and Thompson highlighted the importance of awareness about women’s rights and also the reality that there’s still a long way to go before people unlearn and end the act of justifying violence against women (VAW).

Last March 18, police in Tagaytay City confirmed they had rescued Jalandoni, whose photo of herself with bruises and wounds spread on social media, as she asked for help from friends after she said she had been beaten up and detained by actor Kit Thompson.

Jalandoni’s friends and staff of the hotel, where the pair was staying, had alerted authorities.

Article continues after this advertisementREAD: Kit Thompson allegedly injured, detained girlfriend Ana Jalandoni

Jalandoni was taken to the emergency room while Thompson was taken to a police station for questioning on the same day. On May 19, police filed a complaint against Thompson for violation of Republic Act No. 9262, or the Anti-Violence against Women and Children Act.

Article continues after this advertisementREAD: Police file complaint vs Kit Thompson for allegedly beating girlfriend

Several netizens who reacted to the case expressed shock, disappointment, and anger over the violence inflicted on Jalandoni allegedly by Thompson, her boyfriend.

Some, however, expressed opinions on social media that the beating of Jalandoni “can’t be helped” as the actress must have done something wrong to deserve the violence.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Social media went up on fire also with social media posts quoting Jalandoni as saying she still loved Thompson despite the beating. Other posts directly blamed Jalandoni.

But violence against women is a crime whether it was borne out of love, jealousy or any other reason. There is simply no justification.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Others also questioned the actress for not asking for help sooner. Questions like “why can’t she just leave?” and “why did she stay for so long?” were raised by some people.

Such questions, according to experts, can be considered victim-blaming—the practice of holding victims partly or entirely responsible or at fault for the perpetrator’s crime of violence.

“The reactions shown by the public toward incidents of intimate partner violence prove that we still have a long way to go,” psychologist Anna Cristina Tuazon wrote in a column published on INQUIRER.net on March 24.

“It saddens me that celebrating women’s month in 2022 still means defending a woman’s basic right not to be physically abused,” Tuazon added.

Victim blaming

According to Tuazon, those questions “further serve to blame the victim,” explaining that domestic violence or intimate partner violence is “a legally tricky situation.”

“As a psychologist, I can legally break confidentiality in the event of a child, elderly, or dependent abuse,” she said.

“Since domestic violence is seen as a situation between two otherwise-capable adults, I am only allowed to intervene only if my client is in imminent danger of being victim to homicide. I cannot force my clients to leave their partners,” she added.

Tuazon also cited several possible reasons that many victims of intimate partner violence, or domestic violence, remain in the relationship. Some are:

- societal pressure to keep the family intact instead of prioritizing the woman’s own safety

- belief that children are always better with two parents than one

- valid fear that the woman might be more unsafe if she attempts to leave

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), a US-based nonprofit organization, also listed additional barriers to escaping an unsafe relationship, including:

- fear that the abuser’s actions will become more violent and may become lethal if the victim tries to leave

- unsupportive friends or family

- knowledge of the difficulties of single parenting and reduced financial circumstances

- victim’s lack of knowledge of or access to safety and support

- fear of losing custody of any children if they leave their abuser

- fear that the abuser will hurt, or even kill, their children

- religious or cultural beliefs and practices may not support divorce or may dictate outdated gender roles and keep the victim trapped in the relationship

“Even without children, some women find it difficult to leave due to the psychological cycle of intimate partner violence,” Tuazon said in her column.

“After the violence and abuse, most partners go through a ‘honeymoon phase‘ where they become extra sweet and affectionate, with pleas for forgiveness and promises of never doing it again, making the woman hold out hope that perhaps it is only a ‘one-time thing‘ or that she can ‘make him a better person‘,” Tuazon said.

“At this stage, victims of IPV claim that ‘he is not always bad; he’s nice when he wants to be.‘ Hope (that he will change) springs eternal, and the woman is trapped in a gaslighting cycle of abuse and affection,” she added.

READ: No justification for violence against women

Cycle of abuse

According to studies, most women who are victims of domestic abuse or intimate partner violence often go through the “Walker Cycle Theory of Violence,” a tension-reduction theory which explained that there are three distinct phases associated with a recurring battering cycle: (1) tension-building, (2) acute battering incident or violent episode phase, and (3) loving contrition or honeymoon or remorseful phase.

During the first phase, the batterer starts to become verbally abusive , silent, controlling, possessive, demanding, and may show fits of anger. The violent behaviors at this stage are not yet in an extreme or maximally explosive form.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The woman, on the other hand, will try to control the situation by pleasing the abuser, giving in, or avoiding the abuse. Oftentimes, women, during this stage, would feel unfairly treated, helpless, tense, afraid, embarrassed, humiliated, or depressed.

Eventually, the tension reaches a boiling point and the physical violence begins. The batterer—who studies have shown would usually feel angry and enraged during this phase—would unleash a barrage of verbal and physical aggression toward the woman.

“The woman does her best to protect herself often covering parts of her face and body to block some of the blows. In fact, when injuries do occur, they usually happen during this second phase. It is also the time police become involved if they are called at all,“ said Dr. Larry Beall, director of Trauma Awareness & Treatment Center in the US.

During the third phase, the abuser or batterer will show remorse and feel ashamed of his behavior. He may then exhibit loving, kind behavior followed by apologies, generosity, and helpfulness.

This loving and contrite behavior convinces the victim that leaving the relationship is not necessary.

“This cycle continues over and over, and may help explain why victims stay in abusive relationships. The abuse may be terrible, but the promises and generosity of the honeymoon phase give the victim the false belief that everything will be all right,“ one study noted.

‘Battered women syndrome’

The Walker Cycle Theory of Violence, based on studies, is often linked to the “Battered Woman Syndrome,“ a theory developed in the 1970s and is now associated with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

It is also a psychological concept that has been recognized in judicial proceedings as a valid ground for self-defense. The theory explains why women in abusive relationships find it difficult to leave in spite of repeated instances of emotional, verbal, and physical violence to which they are subjected.

The Battered Woman Syndrome has been used in court cases as a mitigating factor in homicide cases where a battered woman kills her abuser.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

In the Philippines, the Supreme Court—for the first time—recognized the existence of the Battered Woman Syndrome as a legitimate reason to claim self-defense in a case of parricide in the landmark case People v. Marivic Genosa (GR No. 135981, Jan. 15, 2004).

“Though the high court, in a majority decision, fell short of actually exonerating the defendant Genosa, it nevertheless opened the door for her immediate release since she had served the minimum period of her original sentence,“ veteran journalist Randy David wrote in a column published by INQUIRER.net last year.

“The Court thanked Genosa’s counsel, lawyer Katrina Legarda, for bringing the theory of the BWS to its attention,“ he added, referring to Battered Woman Syndrome.

READ: The will to fight back

On March 8, 2004, as people across the world celebrated International Women’s Day, the concept formally became part of RA No. 9262 under Section 26, which stated:

“Victim-survivors who are found by the courts to be suffering from Battered Woman Syndrome do not incur any criminal and civil liability notwithstanding the absence of any of the elements for justifying circumstances of self-defense under the Revised Penal Code.”

Harrowing figures

Data on violence against women collected throughout the years have painted a grim picture of the abuses experienced by many women across the globe.

Estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO) showed that globally, one in three women have experienced either physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner or non-partner in their lifetime.

In the Philippines, data from the 2017 National Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) showed that one in four Filipino women aged 15-49 has experienced physical, emotional, or sexual violence from their husband or partner.

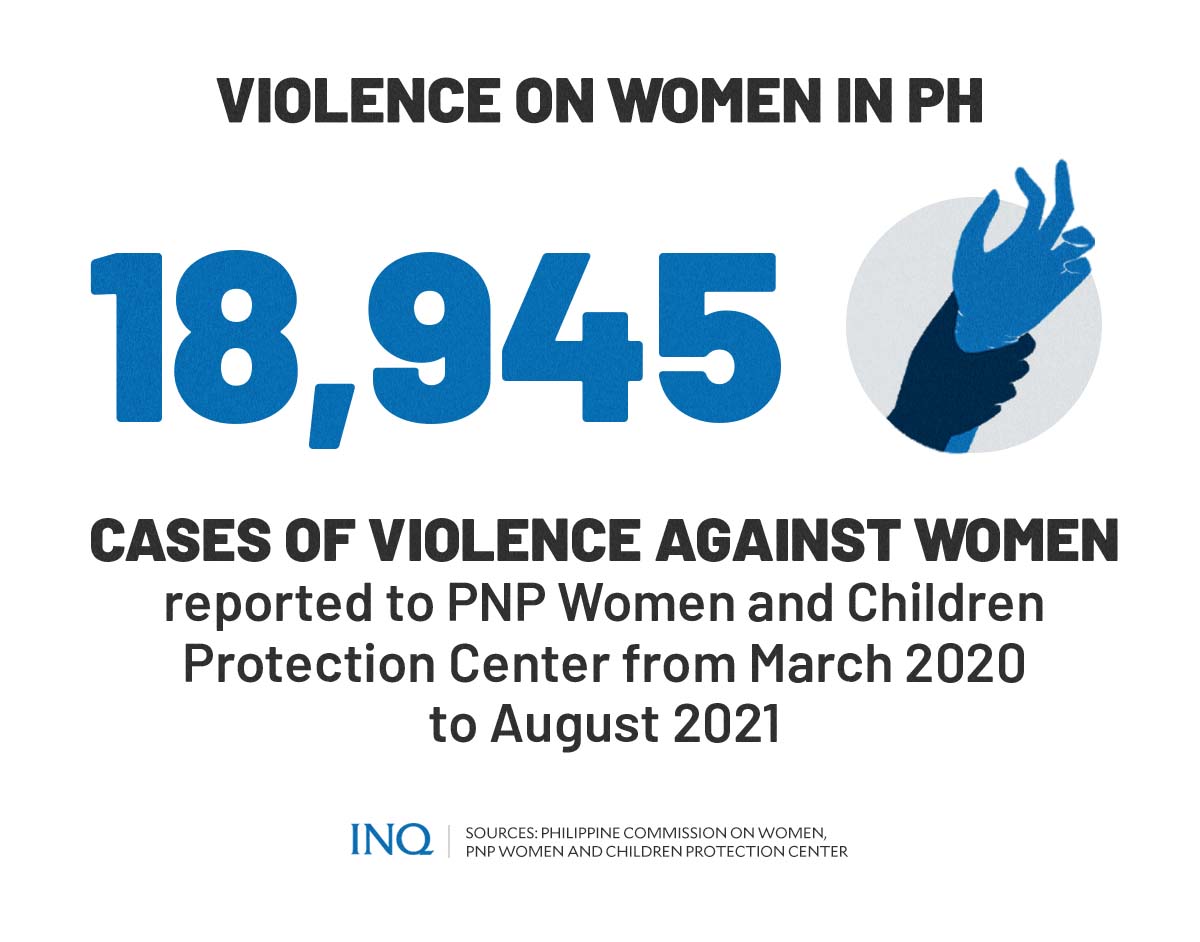

From March 2020 to August 2021, the Philippine National Police (PNP) Women and Children Protection Center received 18,945 VAW cases.

Numbers by the UN Women showed that an estimated 736 million women across the globe—almost one in three—have been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence, or both at least once in their life.

Most violence against women is perpetrated by current or former husbands or intimate partners. More than 640 million women aged 15 and older have been subjected to intimate partner violence (26 percent of women aged 15 and older).

A study by UN Women also found that two in three women across 13 countries report that they or a woman they know has experienced violence at some point in their lifetime.

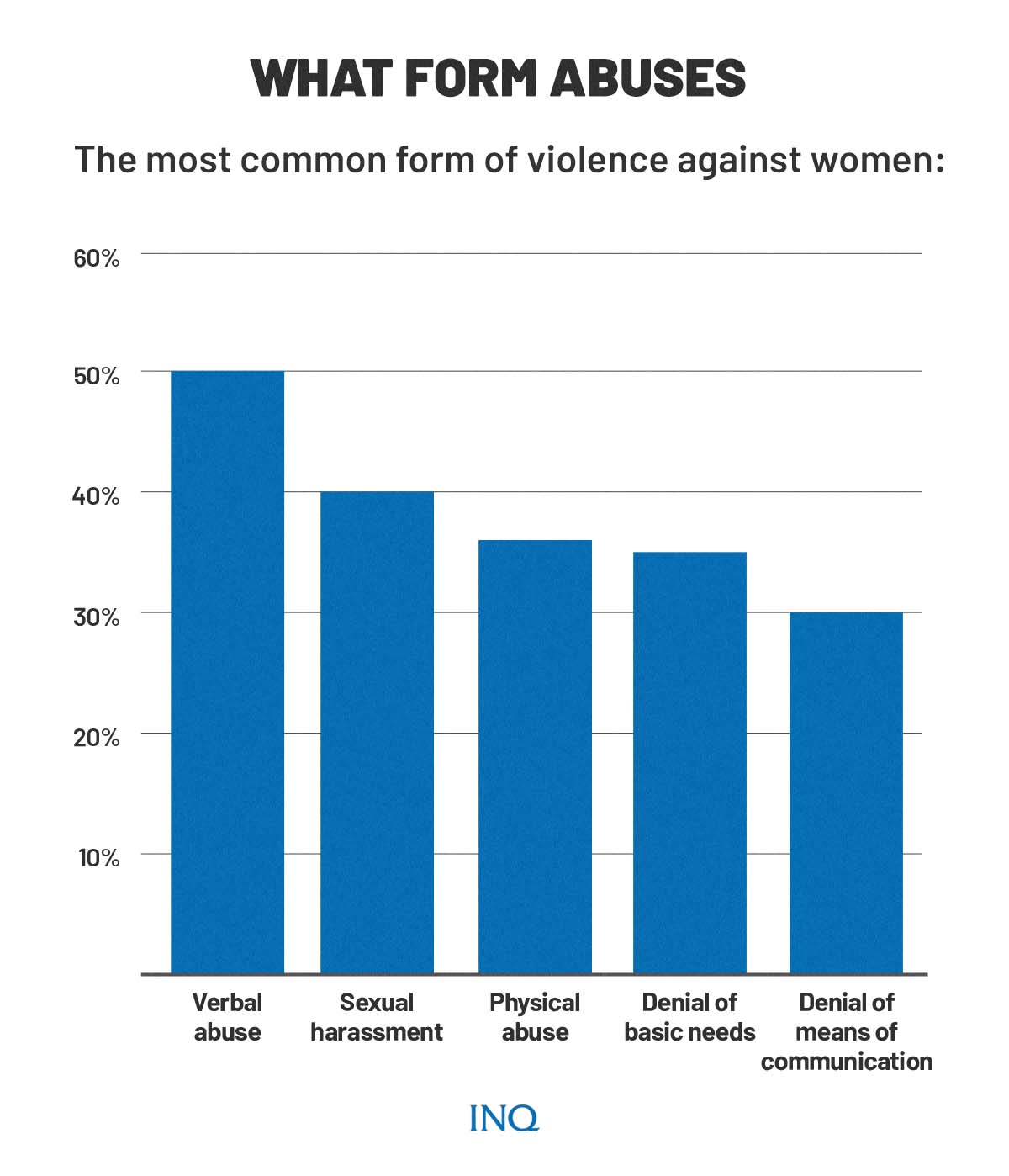

Based on the study, the most common form of violence reported by women include:

- Verbal abuse: 50 percent

- Sexual harassment: 40 percent

- Physical abuse: 36 percent

- Denial of basic needs: 35 percent

- Denial of means of communication 30 percent

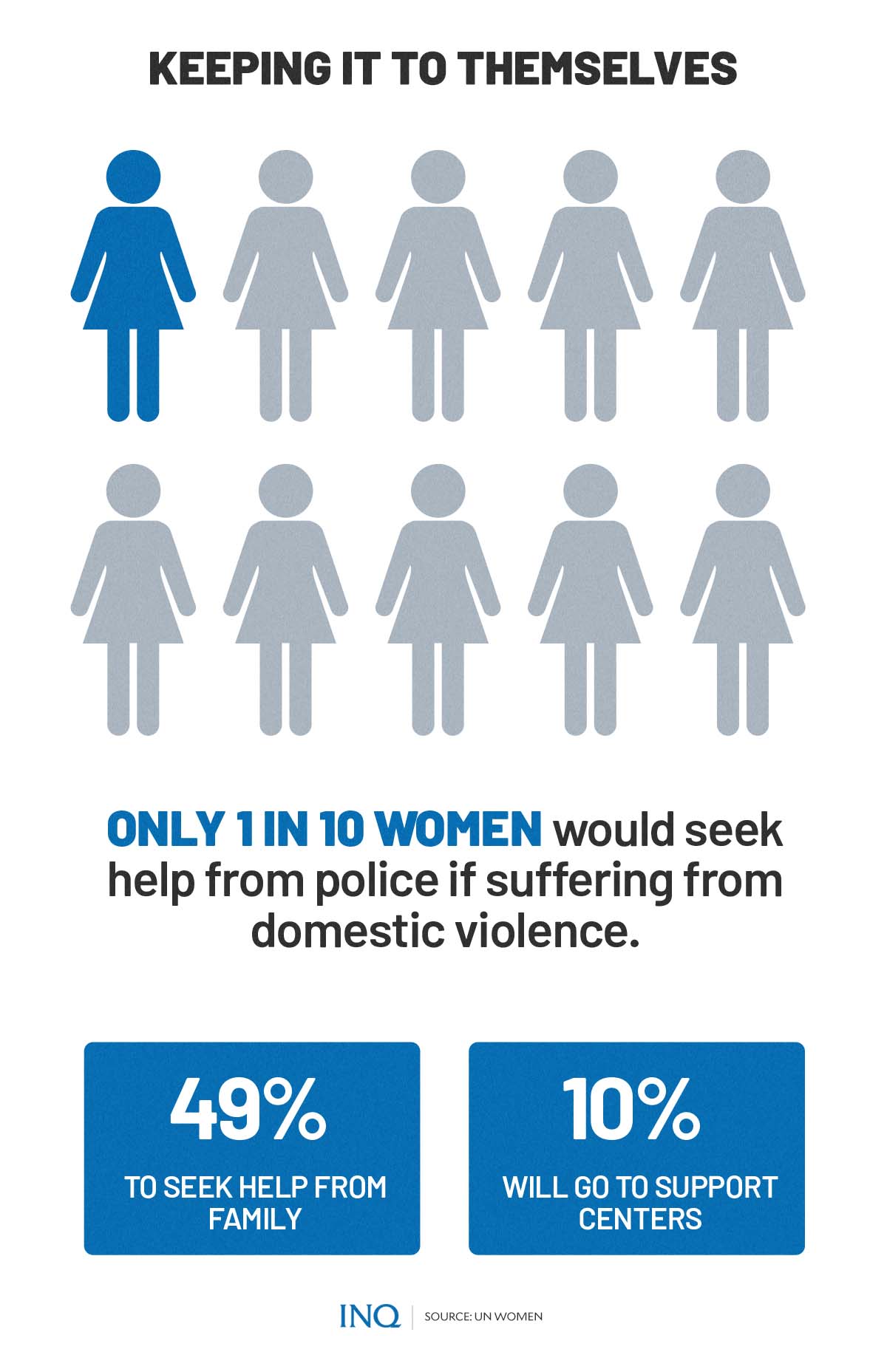

Unfortunately, only 11 percent—or one in 10—would seek help from the police or authorities if they suffered from domestic violence. Around 49 percent said they would seek help from their family, while 10 percent said they would go to support centers.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

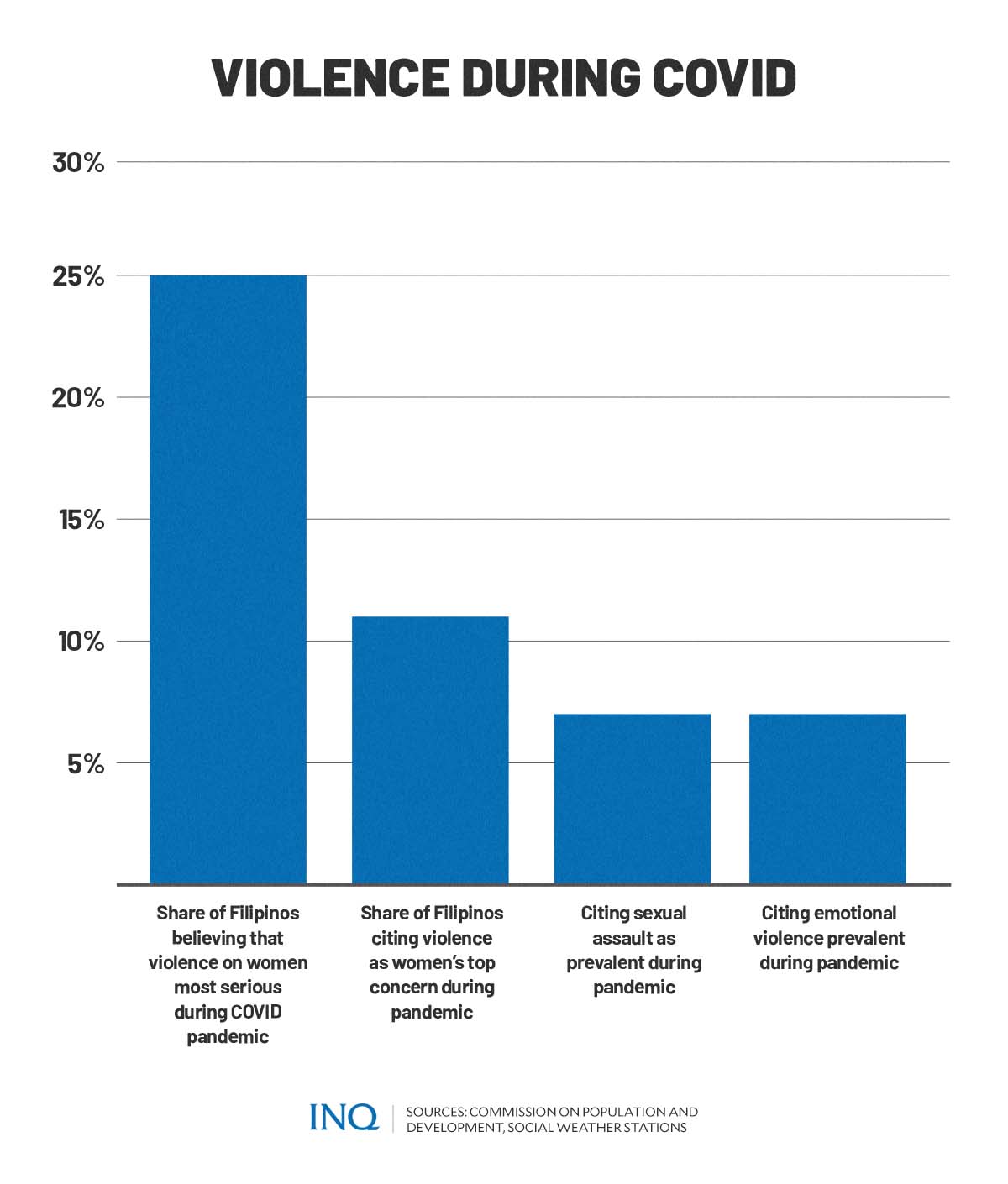

While the Philippines was not part of the UN study, a separate study conducted by Social Weather Stations (SWS) and the Commission on Population and Development (Popcom) in 2020 showed that one out of four—or 25 percent—of Filipino adults, viewed violence as among the most urgent problems faced by women in the pandemic.

The respondents cited three types of violence: physical violence (11 percent), sexual violence (7 percent), and emotional violence (7 percent).

These numbers, however, represent only cases that were reported or recorded. Experts believe that cases of violence against women remain underreported in the Philippines and in other countries—especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) admitted that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has made it harder to provide protection to potential victims of sexual violence in the country.

“Now that the threat of COVID-19 is still looming, it has become harder to help and protect the victims of these kinds of abuse,” CHR said in a series of tweets to mark the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict on June 19, 2020.

“The capacity of authorities like in the case of law enforcement agencies, health providers, and even courts and the judiciary to respond to sexual violence reports — inside or outside the war zones — are still limited,” CHR added.

READ: CHR admits fighting sexual violence harder with pandemic

The Philippine Commission on Women (PCW) explained in a statement in 2020 that the decreasing number of gender-based violence cases may not represent the reality on the ground.

“The decrease in reported cases may be attributed to the restricted movement in the communities, suspension of public transportation, victims being locked down with their perpetrators, lack of communication channels, and lack of information on where/how to report,” PCW said.

READ: As pandemic led to crime decline, it also gave rise to abuses

READ: Lockdown blamed for cases of violence against women

READ: Pandemic curbed Filipinas’ access to gender-based support, violence desks – Oxfam

Seeking help

Between October 2019 and September 2020, the UN Women saw an increase in online searches related to violence against women in the Philippines and seven other countries in Asia.

It was revealed that there was a 63 percent increase in searches relating to physical violence against women while there was a 10 percent increase in searches related to seeking help.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

PCW, however, noted that the “culture of silence” continues to prevail in the country, causing many cases of gender-based violence to go unreported because “many of the victims are ashamed to relate their experiences.”

On March 9, PCW announced that victims of gender-based violence and violence against women—or their family, friends, and witnesses—can ask for help through the Emergency 911 National Hotline.

READ: Abuse victims can ask for help via 911

“If before there were only five cases that 911 responds to which are bombing, terrorism, fire, any calamities, and physical or human emergency, now, the sixth case they would attend to is GBV and VAW,” said PCW chair Sandra Montano.

“If you are too shy to go to the barangay or the police station, you can call 911 right away,” Montano said.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Personal details gathered during the call will remain confidential.

Some of the important and helpful contact information for reporting cases of gender-based violence and/or violence against women include:

- PNP Women and Children Protection Desk: 8532-6690 loc. 177

- CHR portal: https://www.gbvcovid.report/

- Inter-Agency Council on Violence Against Women and their Children: 09178671907, 09178748961, or [email protected]

UN Women listed 10 ways to help end violence against women, even during a pandemic.

These are:

- Listen to and believe victims

- Teach the next generation and learn from them

- Call for responses and services fit for purpose

- Understand consent

- Learn the signs of abuse and how you can help

- Start a conversation

- Stand against rape culture

- Help women’s organizations

- Hold each other accountable

- Know the data and demand more of it

“Remember: It’s okay to ask for help. It’s okay to start again. It’s okay to rest. It’s okay to let go. It’s okay not to be okay,” CHR said in a Facebook post last November.