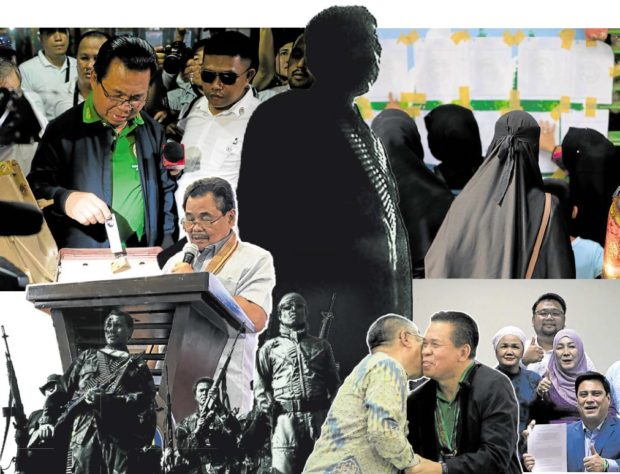

From bullets to ballots in Bangsamoro

TRANSITION | Owing to a 2014 peace deal, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) transitions from being a revolutionary organization to a movement that espouses democratic means to achieve its goals. Composite file images from 2018 and 2019 show MILF chief Ahod “Al Haj Murad” Ebrahim, lead peace negotiator Mohagher Iqbal and the group’s fighters as they campaign for peace initiatives that led to the drafting and eventual ratification of the Bangsamoro Organic Law in a plebiscite on Jan. 21, 2019. —(PHOTOS BY JEOFFREY MAITEM, RICHEL UMEL, JULIE ALIPALA AND RICHARD A. REYES)

COTABATO CITY, Maguindanao, Philippines — Ali Tatak, a former fighter of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) who is in his 60s, said the election on May 9 would be his first time ever to cast his vote for candidates he deemed fit to hold public office.

He registered as a voter in 2019 at Barangay Darapanan in Sultan Kudarat town, Maguindanao province, the base of the once separatist MILF.

“As an MILF member, I did not participate in any election. We were told [that] now is our time to help choose our leaders because it is important for the peace process,” Tatak said in the vernacular in a recent interview outside Cotabato City.

Abdul Latip, a 40-year-old former MILF combatant and among the recently decommissioned fighters, said he voluntarily offered to be subjected to the decommissioning process because he was convinced that the government and the MILF leadership were sincere in ending the so-called Moro conflict that spawned four decades of armed rebellion in Mindanao.

Part of the normalization program for former combatants — in keeping with the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) — is to provide them the opportunity for political participation, mainly by registering as voters.

Article continues after this advertisement“The first electoral exercise I participated in was the plebiscite for BOL. May 9 will be my second time, and this time I will be electing our leaders,” Latip said.

Article continues after this advertisementThe BOL is the Bangsamoro Organic Law, the charter of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) which was ratified during the Jan. 21, 2019, plebiscite.

“This is good, no blood will be spilled, there is no need to fire a gun in battle which will cause civilians to evacuate. What we need now is to choose our leaders wisely, those who will work for the betterment of the Bangsamoro,” Latip said.

Ending conflict

Signed in 2014, the CAB formally ended four decades of separatist rebellion that has claimed an estimated 120,000 lives and left a large part of Mindanao, especially the Moro region, wallowing in underdevelopment.

Under the landmark peace deal, the MILF agreed to drop its members’ firearms in exchange for, among others, redoing the Moro autonomy setup by giving it greater governance powers, conceding to it a fixed share in national revenues which spending they alone will decide, and ensuring funding support for rehabilitation of war-torn communities and decommissioning of some 40,000 combatants and their weapons.

Other key aspects of the peace deal are recognition of Moro identity and acknowledgment of historical injustices through succession of government actions and policies that disfavored and discriminated them as a people.

The CAB was the basis for legislating the BOL. With the BARMM established in 2019, 12,000 MILF combatants were immediately decommissioned. The process for a second batch of 14,000 is under way.

In the peace deal, the MILF committed to transition from a revolutionary organization to a social movement that espouses democratic means to achieve its aims. This is the reason it formed the United Bangsamoro Justice Party (UBJP) in 2014.

During the first quarter of 2015, the members of the MILF, led by its leaders, started the first step of their participation in the country’s electoral process, as registered voters.

In 2018, in the run-up to the plebiscite for the BOL, the UBJP campaigned for its members and supporters to register as voters. The Commission on Elections said more than 150,000 former MILF fighters had registered and eventually voted during the BOL plebiscite.

First poll exercise

Due to delays in building the BARMM, the MILF’s political transition also suffered setbacks. As such, the UBJP will be participating in its first electoral exercise on May 9.

In one party assembly, UBJP secretary-general Abdulraof Macacua urged grassroots leaders to elect candidates with integrity and credibility, and for those seeking reelection, good track record of public service.

Lawyer Naguib Sinarimbo, who is UBJP deputy secretary-general, said they had issued guidelines for its members to follow in choosing leaders.

“We guide our members how to correctly vote but did not dictate who to elect,” Sinarimbo said, even as he advised the electorate “to reject the politics of money for it will make the elected officials corrupt.”

“Corrupt and dishonest candidates, once elected, will recover all his expenses through corruption,” said Sinarimbo, who is also interior minister of the BARMM whose interim Chief Minister, Ahod “Al Haj Murad” Ebrahim, the MILF’s chief, has vowed to rule along the precepts of moral governance.

Abunawas Maslamama, a senior MILF official who uses the nom de guerre Von Al-Haq, said while the CAB forced the erstwhile rebel organization into the electoral arena, its political agenda will remain, and that is “to emancipate our people from the bondage of political, cultural and socioeconomic deprivation and exploitation.”

This is why the UBJP is organized as “a political vehicle where we can entrust our development, progressive agenda for the Bangsamoro,” explained Maslamama, deputy minister for transportation and communication in the BARMM.

“UBJP is a principled political party which totally represent[s] the voice of the broader populace and not any political family or clan,” he added.

Ebrahim admitted that joining the political and democratic processes of the country is a major challenge for them given that corruption is like a built-in feature of the government.

Moral goals

It is in this context, Ebrahim said, that their battle cry of moral governance was shaped. He said they would govern the BARMM without imposing Islamic governance but rather impose the moral virtues of Islam which is for all humankind.

Amid the systemic flaws that it has to live with, the MILF will have the chance to build an electoral system for the Bangsamoro region that hews along its moral goals.

Sinarimbo said the proposed Bangsamoro Electoral Code that they are firming up hopes to address the weaknesses in the current political system.

Among its salient features is the antidynasty provision and a prohibition of “political butterflies,” or “turncoatism.” With a parliamentary setup, the Bangsamoro government needs to have a strong and functional political party system.

Another electoral code feature is the prohibition on tandems or slate coming from the same family in a given locality.

“What we are trying to avoid is the concentration of power in a local government into a single clan or family, like a father as mayor, the wife as vice mayor, and the children as council members. What is allowed, for example, is either the father or mother as mayor, but the other family members can seek elective posts in the province,” Sinarimbo explained.

Alliances

For its first foray into electoral battle, the UBJP has entered into alliances with political dynasties, especially in the provinces of Maguindanao and Lanao del Sur.

In Maguindanao, it endorsed the gubernatorial bid of Rep. Esmael Mangudadatu who vigorously pushed for the enactment of the law extending by another three years the MILF-led Bangsamoro Transition Authority.

In Lanao del Sur, the UBJP struck an alliance with the local Siap Party, in the process backing the reelection of Gov. Mamintal Alonto Adiong Jr., whose clan is a known supporter of the Bangsamoro cause.

The UBJP’s endorsement is also being sought by national politicians, especially those running for president. Ebrahim has already announced that they will endorse presidential and vice presidential candidates to help elect national leaders who are committed to the continuity of the Bangsamoro peace process.

Ebrahim, who is UBJP president, said they were endorsing candidates who they believed were pursuing the same vision and agenda as theirs.

“The world is watching us. They see the GPH (Government of the Republic of the Philippines)-MILF peace process as [a] model and there is no room for failure,” Macacua said.

RELATED STORIES

Iqbal tells Bangsamoro: We can’t support a candidate who’ll bring back past horrors

Peace taking more time in Bangsamoro – third party observers