National Children’s Month: Cause for celebration or worry?

SEEKING HELP. Victims of sexual violence turn to Sagip Center in Muntinlupa City for support and protection against their attackers. MARIANNE BERMUDEZ FILE PHOTO

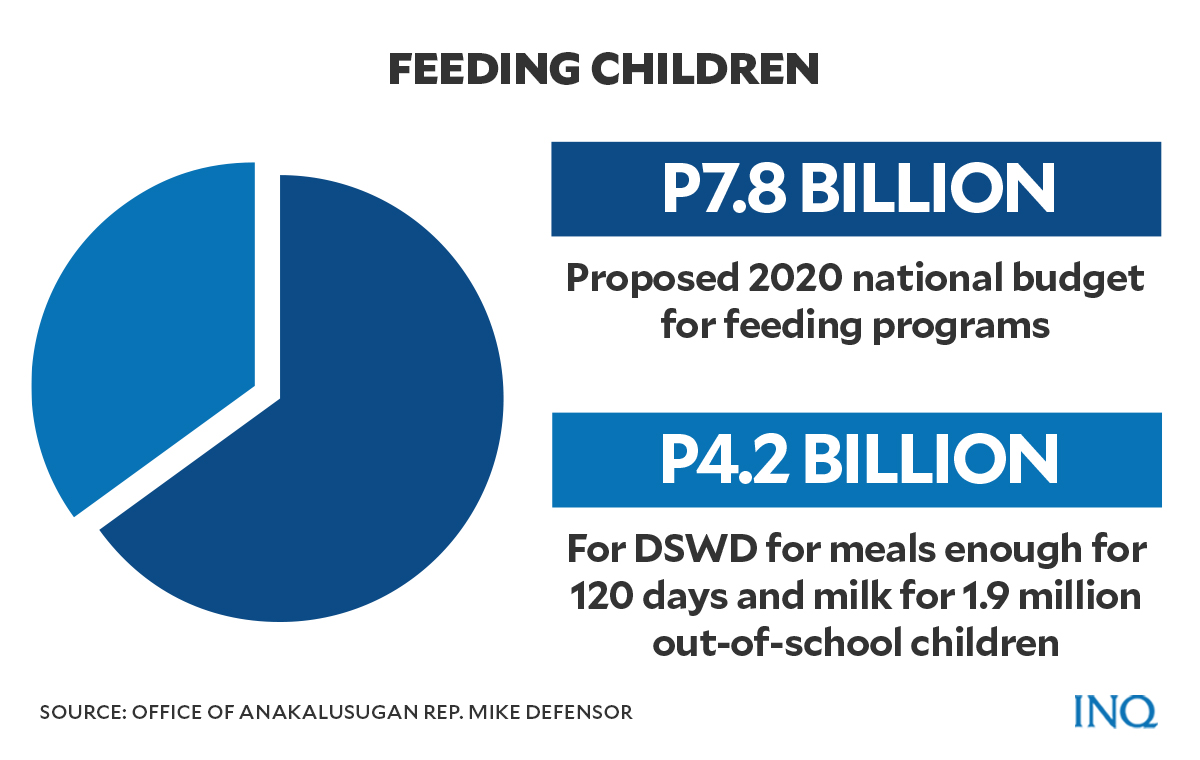

MANILA, Philippines—At least P7.8 billion has been earmarked in the proposed 2022 national budget for a feeding program for children, according to Anakalusugan Rep. Mike Defensor.

But as the country celebrates National Children’s Month this November, would the funding be enough to address the many challenges that confront Filipino children especially amid the pandemic?

November, as National Children’s Month, has been made official by Republic Act No. 10661, signed by the late President Benigno Aquino III in 2015.

The declaration commemorates the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child by the United Nations General Assembly on Nov. 20, 1989.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the National Youth Commission (NYC), and the Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC)—as lead agencies—were tasked with the launch of activities in relation to National Children’s Month.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Department of Education (DepED) and the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) were tasked with facilitating and encouraging the commemoration in all private and public schools nationwide.

Article continues after this advertisementIn this report, INQUIRER.net will present data on the situation of children in the Philippines amid the pandemic and in observance of National Children’s Month.

P7.8B budget to feed children

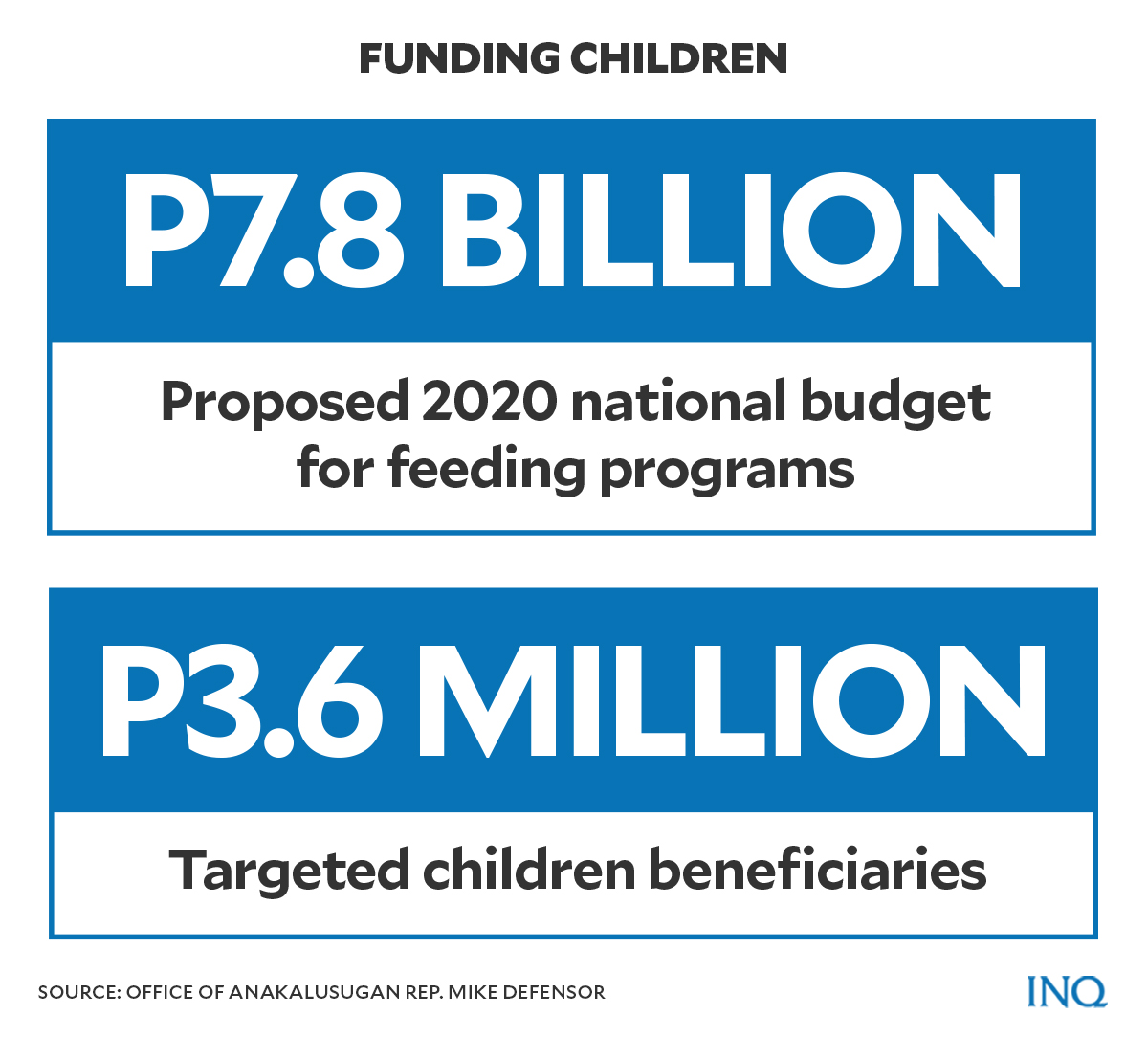

At least P7.8 billion was earmarked in the 2022 national budget for feeding programs which, according to Defensor, will benefit over 3.6 million undernourished children in the country.

“We are counting on the national government’s targeted feeding programs to help improve the nutritional and overall health condition of children from poverty-stricken families who continue to suffer from hunger,” said Defensor, who is also vice chair of the House Committee on Welfare of Children (CWC).

Citing results of a Social Weather Stations survey released last July, the lawmaker said that “an estimated 3.4 million Filipino families experienced involuntary hunger – hunger due to lack of food to eat – at least once in the past three months.”

READ: SWS: 3.4 million hungry Filipino families in 2nd quarter of 2021

From the P7.8 billion budget that has been set aside by Congress, P4.2 billion will go to DSWD for 120 days worth of meals and milk for 1.9 million children aged two to five years old.

According to Defensor, the feeding program will target underfed children who are “not formally enrolled in kindergarten.”

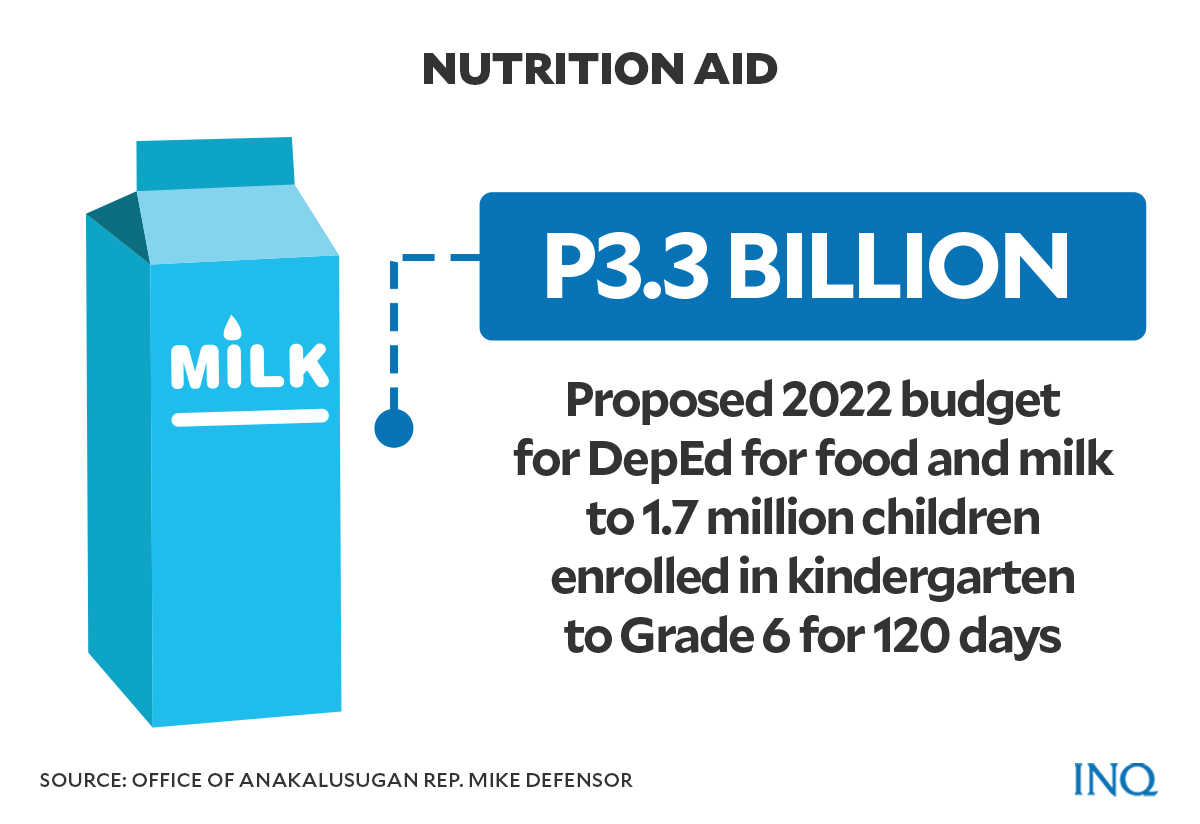

Aside from DSWD, the School-Based Feeding Program (SBFP) of DepEd will also get its share of the budget next year with P3.3 billion, which will be used to supply nutritious food products (NFPs) and fresh milk to 1.7 million learners from kindergarten to Grade 6 for a period of 120 days.

The DepEd has switched the SBFP’s hot meals to NFPs and fresh milk when the education system in the country shifted to distance learning due to COVID-19.

The food supplies can be either picked up by parents from designated collection points or delivered to houses once or twice a week.

“The SBFP targets wasted and severely wasted learners, or those deemed too skinny for their age,” said Defensor.

The Department of Health (DOH) will receive P250 million for its Complementary Feeding Program, which will cover the expenses for therapeutic milk and protein-enriched meals.

These will help improve the nutrition of infants aged six to 23 months. The program will also benefit breastfeeding mothers.

Aside from that, the DOH’s National Nutrition Council will also get P139 million for its Early Childhood Care and Development in the First 1,000 Days Program.

According to Defensor, the program focuses on providing food aid to pregnant women who are considered nutritionally at-risk.

Constant problem

According to World Bank, malnutrition among children has perennially been a serious problem in the Philippines.

Malnutrition, according to the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST}, refers to the pathological state—general or specific—resulting from a relative or absolute deficiency or excess in the intake of one or more essential nutrients.

This may manifest clinically or detectable by physical, biochemical, or functional signs or both. The different forms of malnutrition are undernutrition, specific nutrient deficiency, overnutrition, and imbalance.

The World Bank said that the Philippines “ranked fifth among countries in the East Asia and Pacific region with the highest prevalence of stunting and is among the 10 countries in the world with the highest number of stunted children.”

Stunting, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), means that the height of a child or individual is low for his or her age.

“It is the result of chronic or recurrent undernutrition, usually associated with poverty, poor maternal health and nutrition, frequent illness and/or inappropriate feeding and care in early life,” WHO explained.

“Stunting prevents children from reaching their physical and cognitive potential,” it added.

Data from World Bank showed that micronutrient undernutrition continues to plague children in the Philippines.

At least 38 percent of infants aged six to 11 months old and 26 percent of children aged 12-23 months old suffer from micronutrient undernutrition in the country.

“Nearly 17 percent of children aged 6–59 months suffered from vitamin A deficiency, of which children aged 12–24 months had the highest prevalence (22 percent) followed by children aged six to 12 months (18 percent),” the World Bank said.

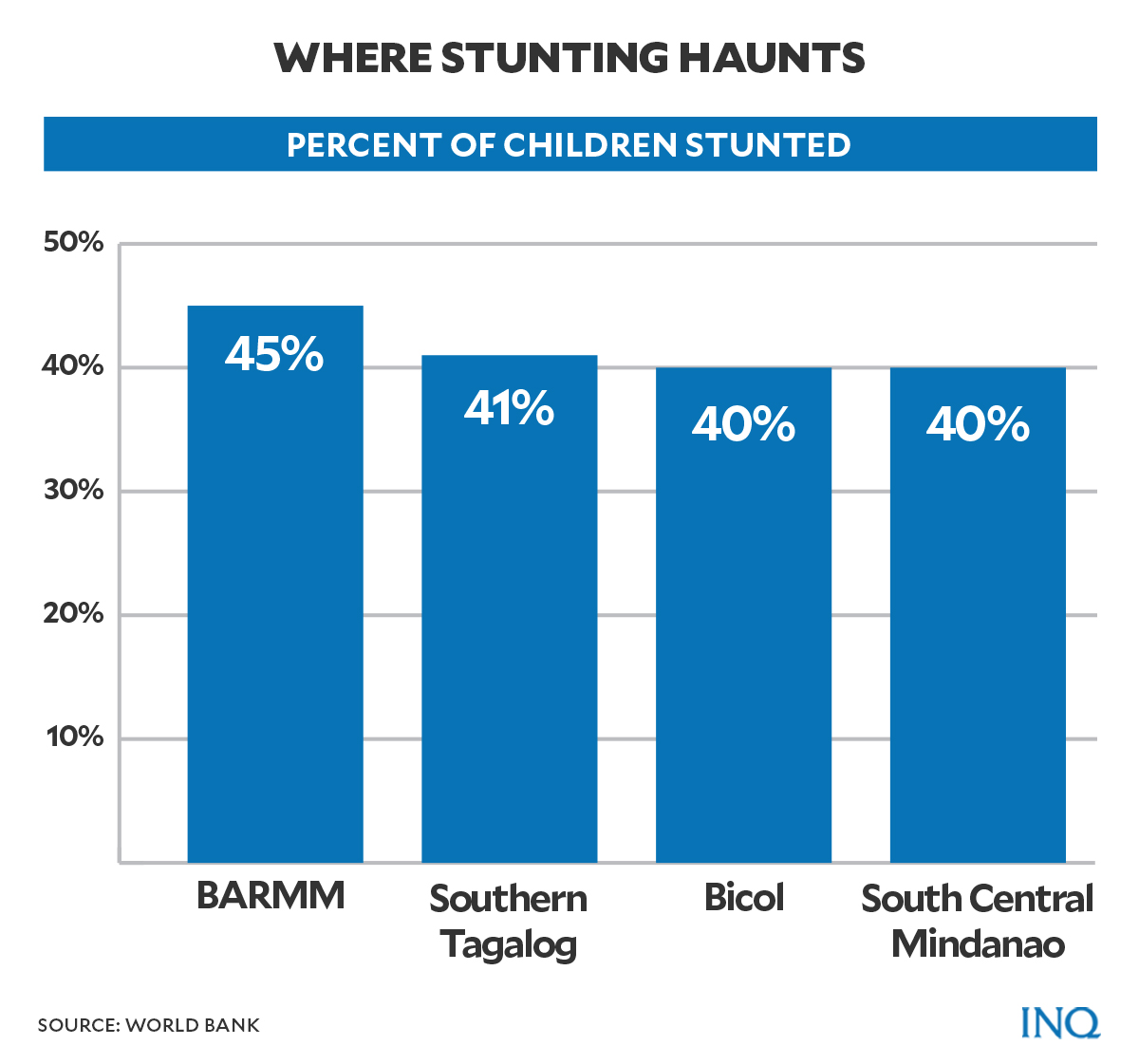

There are five regions in the country where cases of stunting have exceeded 40 percent of the child population. According to World Bank, these are:

- Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)—45 percent

- Southwestern Tagalog Region (Mimaropa)—41 percent

- Bicol—40 percent

- South Central Mindanao Region (Soccksargen)—40 percent

- Western Visayas—40 percent

According to United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef), at least 95 children in the Philippines die from malnutrition daily. Around 27 out of 1,000 Filipino children, sadly, do not get past their fifth birthday.

A third of Filipino children were also stunted. Stunting after two years of age can be permanent, irreversible, and even fatal, according to Unicef.

“Apart from high rates of stunting and neonatal deaths, low routine immunization coverage and lack of access to clean water and sanitation facilities also threaten children’s survival and development in the Philippines,” Unicef said.

By the numbers

The 2018 Expanded National Nutrition Survey (ENNS) of the DOST-FNRI detailed the cases of malnutrition and stunting among Filipino children before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country.

According to the ENNS report, the number of underweight, stunted, wasted—low weight for height—and obesity cases among preschool children, school-age children, and pre-adolescents and adolescent children were:

Preschool children

- One out of five, or 19.1 percent, of preschool children was underweight, with the highest prevalence (21.9 percent) among children aged 4 to 4.9 years old.

- Three out of 10, or 30.3 percent, of children under five years old were stunted, with the highest prevalence (36.6 percent) recorded in the first year of life.

- The national estimate for under-five wasted children was 5.6 percent, with the highest prevalence among 0-5 months old (8.6 percent).

- The prevalence of overweight-for-height children in 2018 was 4 percent.

- Overweight-for-height among children aged 0-5 months was 5.2 percent.

School-age children

- One in four, or 24.5 percent, of school-age children was stunted.

- Wasting prevalence among school-age children was 7.6 percent in 2018.

- The national estimate for overweight children in 2018 was 11.7 percent. The FNRI noted an increasing trend of overweight cases and obesity among school-age Filipino children through the years.

Pre-adolescents and adolescent children

- The stunting rate among adolescents in 2018 was 26.3 percent, with the highest prevalence (30.3 percent) among teenagers aged 16 to 19 years old.

- Wasting prevalence among this age group was 11.3 percent in 2018.

- The prevalence of overweight cases and obesity rose among pre-adolescents and adolescent children rose in 2018 at 11.6 percent.

The report also found that the prevalence of underweight, stunted, and wasted children among different age groups differ in urban and rural areas.

Preschool children

- There was a higher prevalence of underweight children below five years old among those residing in rural areas at 22.6 percent than in urban areas at 15.4 percent.

- The stunting rate among the same age group was also higher in rural areas at 34.3 percent, while the prevalence in urban areas was at 4.6 percent.

- There were more wasted children from rural areas (6.6 percent) than in urban areas (4.6 percent).

- Overweight-for-height among children below five years old was more common among urban dwellers at 4.9 percent.

School-age children

- Undernutrition was more prevalent among children in rural than in urban areas as evidenced by higher underweight (28.2 percent vs. 21.2 percent) and stunting (28.0 percent vs. 20.5 percent) rates.

- The prevalence of overweight or obesity was more common among children in urban areas at 15.8 percent than in rural areas at 8.2 percent.

Pre-adolescents and adolescent children

- Adolescents from rural areas (29.2 percent) were more likely to be stunted than their urban (23.0 percent) counterparts.

- Overweight cases and obesity were more prevalent among adolescents from urban areas (15.4 percent) than those from rural areas (8.4 percent).

FNRI also detailed the disparity in cases of underweight, stunted, wasted, and overweight children among those who were from the poorest households compared to their richer counterparts.

COVID impact

The CWC, citing data from the Philippine Pediatric Society, said in a statement that from March 2020 to February 2021, there were 48,411 children aged 19 and below who have contracted COVID-19.

Amid the rising cases of the highly transmissible Delta variant, the DOH also observed increasing cases of COVID-19 infection among children.

READ: Alarm bells ring over rising Delta infections among PH kids

The CWC said as of August 8, the number of COVID cases among children has risen “rapidly” to 176,540 with 466 deaths.

To provide better protection for children against the disease, the government said last week that it will begin the national rollout of COVID vaccination for minors aged 12 to 17 years old “as early as November 3.”

READ: PH vaccination drive enters new phase—children, minors

The government is currently implementing Phase 2 of pediatric vaccinations for children with comorbidity in several Metro Manila hospitals and vaccination sites.

According to the health department, as of Oct. 16, a total of 1,509 children with comorbidity, or pre-existing health conditions, have received their first vaccine dose.

Adjusting to new normal

According to the CWC, the theme for the 29th National Children’s Month Celebration is “New Normal na Walang Iwanan: Karapatan ng Bawat Bata Ating Tutukan!.”

“2021 poses greater challenges as the country reels from the prolonged consequences of the pandemic. These challenges continue to aggravate underlying issues on children and threaten to undermine the collective efforts of the civil society in handling the pandemic,” the CWC statement read.

“The 29th NCM focus and theme for this year will cover the myriad of issues on children rights to survival, development, protection, and participation in the new normal setting,” it said.

“As the Philippines gears eagerly towards ensuring the safety and protection of all Filipinos, the call for inclusivity remains relevant—especially in putting a high premium on children’s rights,” it added.

Aside from malnutrition and COVID-19 cases, this year’s celebration will also cover issues, like mental health issues among children amid the pandemic.

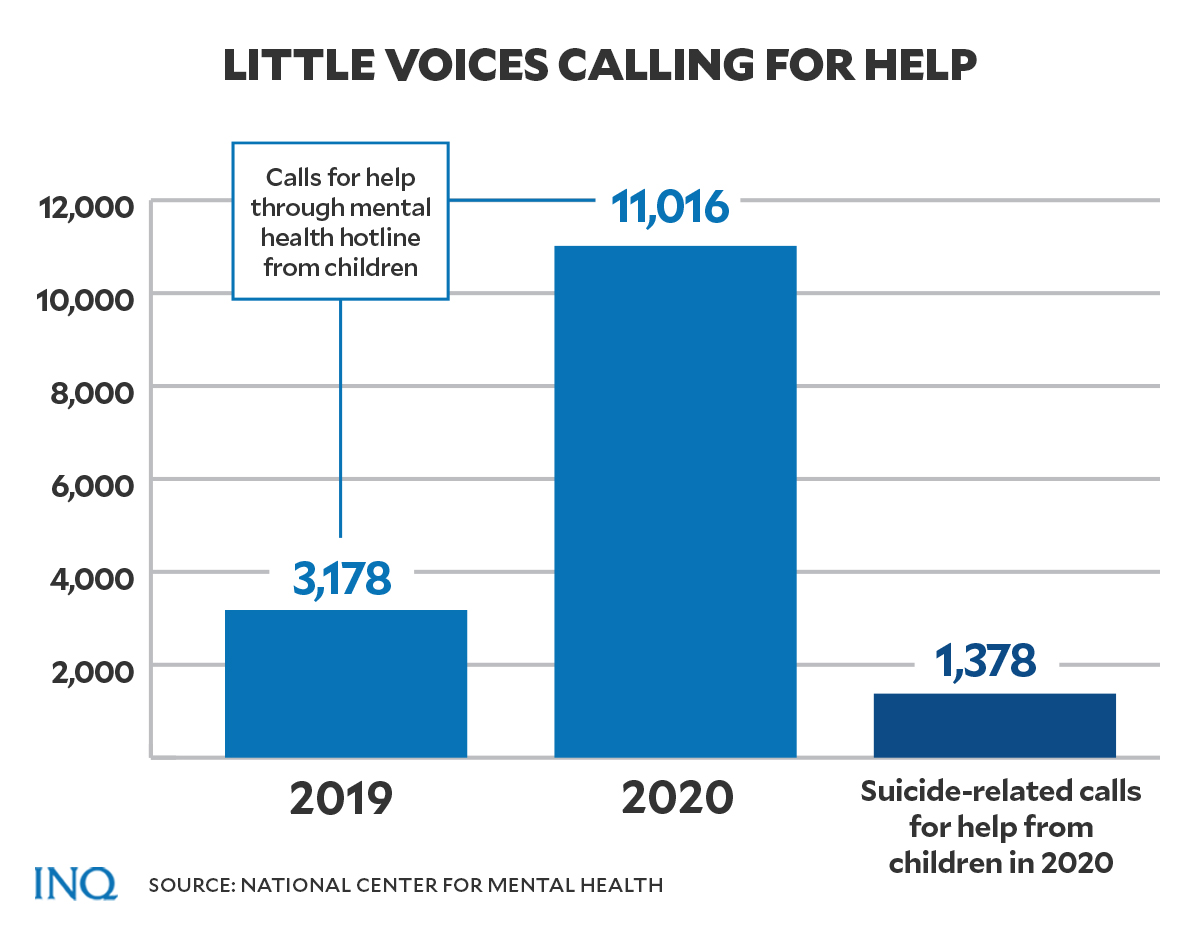

Data from the National Center for Mental Health Crisis Hotline showed that the number of calls from children seeking help spiked by 347 percent from 3,178 in 2019 to 11,016 in 2020.

The CWC said that it was alarming, given that 12.48 percent or at least 1,375 of the total number of calls received last year were classified as suicide-related calls.

In October last year, the group Samahan ng Progresibong Kabataan reported 17 suicide cases among students last school year.

The mental health problem among children was also heightened by the pandemic, as children were left with no choice but to stay inside their houses.

“Before, if there are troubles inside the house, the school can be a place where they could have a sense of emotional and social support from friends and the people in school who are present physically,” said child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr. Mary Daryl Joyce Calleja.

Education Secretary Leonor Briones said last September that these psychosocial problems among young learners amid the pandemic are a “big challenge for our people in government.”

READ: The crisis within: Suicides rise as COVID takes its toll on lives, livelihood

The CWC also highlighted the alarming increase in the number of cases of violence committed against children since last year.

Citing data from the Philippine National Police (PNP), the CWC said a total of 19,652 cases of violence against children was reported in 2020. From January to May this year, the number was already 5,464. The majority of victims were female, the CWC said.

Children aged 10 to 17 years old “are significantly the ones who are often victimized,” it said.

Cases of gender-based violence included violations of several laws in the Philippines:

- Provisions of the Revised Penal Code against acts of lasciviousness and concubinage

- Republic Act 9262 or the Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act

- Republic Act 8353 or the Anti-Rape Act

- Republic Act 9995 or the Anti-Photo and Video Voyeurism Act

- Republic Act 9208 or the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act

- Republic Act 7877 or the Anti-Sexual Harassment Act

- Republic Act 11313 or the Safe Spaces Act

READ: As COVID shuts down schools, homes become unsafe places for kids

The CWC has prepared a series of activities for the whole month of November. The theme for each week will focus on the four categories on children’s rights including survival rights, development rights, participation rights, and protection rights.

A launching ceremony was scheduled on Nov. 3, which will mark the start of this year’s celebration of National Children’s Month.

TSB

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.