SMC scuttles land donation to healing priest

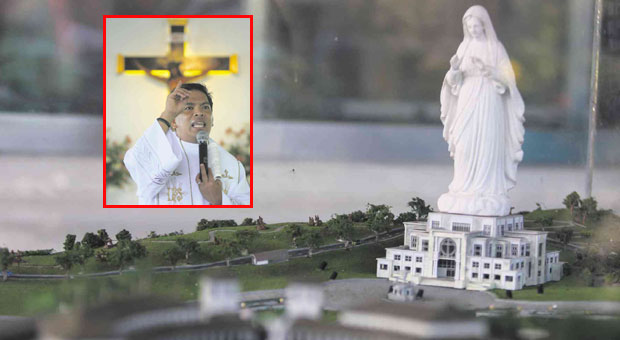

‘MEGA-SHRINE’ A scale model of the proposed Mary Mother of the Poor shrine for devotees of healing priest Fr. Fernando Suarez (left) stands on a 33-hectare property donated by San Miguel Corp. in Alfonso, Cavite, where a statue of the Blessed Virgin is envisioned to rival the famous Christ the Redeemer towering 30 meters high in Brazil. LEO SABANGAN II/ MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

(First of a series)

A deal between San Miguel Corp. (SMC) and healing priest Fr. Fernando Suarez to build a “mega-shrine” to Mother Mary with a statue that would be taller than the 30-meter-high Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro has collapsed, the Inquirer has learned.

SMC’s concerns about the management of the project and financial issues involving the priest’s Mary Mother of the Poor (MMP) Foundation derailed what on paper was supposed to be a one-of-a-kind project rivaling some of Christendom’s grandest religious sanctuaries.

Suarez is on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and cannot be reached for comment.

The agreement for the donation of SMC’s 33-hectare property in Alfonso, Cavite, was reached four years ago. The shrine was to be called “The Healing Center of the Blessed Virgin Mary at MonteMaria.” From all indications, however, this plan will no longer push through, or at least not on the same site.

Article continues after this advertisementSMC and the MMP are set to announce this week that they will dissolve their agreement on the donation located in SMC’s 125-hectare property.

Article continues after this advertisement“The deal is off,” said a source familiar with SMC’s side of the issue, pointing to provisions of the agreement that required the MMP to construct the church within five years of receiving the property donation.

The source noted that the MMP had asked for an extension, but that SMC was not inclined to agree to it.

“If San Miguel had seen that there was significant progress being made, I think it would have been inclined to give an extension,” the source said, adding that the foundation has so far failed to present viable plans for the shrine.

This jibes with information from MMP officials. They conceded that the estimated P1 billion needed to build the shrine was beyond their ability to raise.

The foundation had earlier put forward suggestions on how they could raise the necessary funds, including using the land as collateral to obtain a bank loan or selling slots in a columbarium that would be built on the property. Both ideas were vetoed by SMC.

SMC concerns

More importantly, however, SMC officials had grown increasingly concerned in recent years about the handling of MMP’s assets. These consist of donations from devotees and the Cavite property, which constituted its single biggest asset.

“San Miguel is worried about how the money is managed,” said the source, who added that disagreements among members of the old MMP board regarding the disposition of funds prompted Suarez to form a new board of directors.

The source pointed out that SMC had “spent millions,” including tax payments necessary for the transfer of the property’s ownership, while progress on the part of the foundation had been insufficient.

But according to Deedee Siytangco—a member of the foundation’s current board of directors, and a Suarez devotee since 2006—the MMP’s early days were “a learning experience” for its officials.

“In the beginning, it was a tayo-tayo family-type [affair],” she said.

A board member, Manuel Sta. Cruz, said that the MMP commissioned an audit from the accounting firm SGV & Co. last year, and had sought and received accreditation from the Philippine Council for NGO Certification.

“With the new board, we’ve legitimized everything,” Siytangco said, “because we were also concerned that people were talking [about it].”

“We want to feel comfortable about ourselves when we’re dealing with people who want to give money to the foundation,” she explained.

Previous to the SMC deal, the MMP was supposed to build its shrine in Batangas City on a 5-hectare property owned by Hermilando Mandanas, a former Batangas governor and representative.

Face-saving move

The donation fell through in 2010, and no official reasons were given by either side at the time.

“The simple fact is that we thought he had donated it to the foundation. As it turned out, he donated it to the archdiocese,” Siytangco said. “So we couldn’t work on that basis because we were going to build a nice shrine there. We had to leave because we couldn’t work with those conditions.”

With a sigh, she recalled Suarez as saying, “We can’t stay where we’re not welcome.”

“We’re not talking about the San Miguel donation and the vision of Father Suarez to build a shrine there,” lawyer Lorna Kapunan said about the joint statement to be issued.

“So let’s not talk about the San Miguel property, their donation and what the board has decided,” she said. “I speak for both because I am a retained counsel of San Miguel and I do pro bono work for Father [Suarez]. I believe in him.”

Sources from both camps said that this joint statement—expected to be issued this week—is meant to provide a face-saving way for both parties to undo the donation.

“Even if this project won’t push through, we don’t want San Miguel to look bad because we did benefit from the property during our stay,” said an MMP official. “We’ve been holding healing Masses there for the last four years which thousands of people have attended.”

Passionate devotees

Siytangco and fellow devotee Baby Ignacio were passionate in their defense of Suarez, saying he was a simple man whose main activity outside his priestly duties was playing tennis.

Ignacio pointed out that Suarez was initially uncomfortable about his supposed gift of healing, which had attracted thousands of devotees here and overseas.

According to her, there was a case in Canada early in Suarez’s career where the patient died before he could pray over her—because a blizzard had prevented him from coming earlier—but reportedly came back to life when he came to bless the body a few hours later.

Many of the stories about Fr. Suarez’s “miracle cures” are difficult to verify. Some of the most comprehensive—and arguably, the most authoritative—information available can be found online in three websites: www.montemaria.ph, www.marymotherofthepoor.org and www.fatherfernando.com.

The homepage of the MMP congregation even has a section dedicated to informing the faithful about the Monte Maria project. These included several links detailing how donors can help underwrite its construction costs via credit card and PayPal accounts, mailed check donations, and transfers and deposits to bank accounts both in the Philippines and in North America.

Most telling, however, were links on the website labeled “events supporting the project,” “project progress” and “fund-raising progress report.”

The pages were blank.

(Next: Audit report)

RELATED STORIES

Congregation for healing priest