CCT goal of easing poverty still way off

MANILA, Philippines — Cristina Dades of Pasay City is a beneficiary of the government’s conditional cash transfer (CCT) program.

On her fourth year, Dades, a parent leader of Barangay 178, took out a P10,000 loan from the livelihood program of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) to put up her own “sari-sari” or variety store while she continues to receive a P1, 100 monthly allowance provided under the agency’s CCT scheme or Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps).

She is one of three million CCT beneficiaries that President Benigno Aquino III targeted for the government’s anti-poverty program in his 2011 state of the nation address.

But while Dades managed to make something of her life, the same could not be said for other recipients.

Delisted beneficiaries

DSWD records presented during a joint oversight committee hearing in the Senate last Thursday, July 12, showed that as of June 27, 2012, a total of 29, 946 were removed from the list of beneficiaries.

Of the number, 14,166 were delisted because they were not eligible; 6,614 were included on an error; 2,619 have no children with age 0-14, a prerequisite to avail of the monthly allowance; 2,353 have moved to a non-program area; 2,114 have waived the benefit; 1,912 committed fraudulent acts; and 168 were no longer “poor” as defined by the DSWD.

Article continues after this advertisementBut Dades, 40, and Gladys Bascal, also a beneficiary, told INQUIRER.net in separate interviews that an undetermined number were removed from the CCT program because of gambling.

Playing “tong-its” (a card game) or bingo were more important to a lot of the poor that they would rather give up the financial assistance that the government was offering them.

Dades noted how some of her neighbors would rather give up their allowance than gambling.

“One neighbor requested a waiver that gave the DSWD the authority to delist him as a beneficiary,” Dades said in Filipino.

Bascal, who benefitted from the program for three years starting in 2008, said a fellow recipient was using the money he got for gambling and illegal drugs.

“He was gambling and he was no longer attending the required meetings,” said Bascal, who was delisted from the program in 2011 after the DSWD assessed that her family no longer needed the government’s financial aid. Her husband now works abroad and they have their own store.

Bascal said that in some cases, some beneficiaries, who were in dire need of money, pawned their government-issued ATM cards that would enable them to withdraw the money deposited by the DSWD at the Land Bank of the Philippines.

“A lot of them are stubborn. They have pawned their ATMs even before they could receive their cash grants, which they would use to pay off the loans they advanced,” she said.

‘Usual violation’

These stories by Dades and Bascal were confirmed by Joy Acuna, DSWD’s “link” to the beneficiaries in Pasay City.

“The usual violation is gambling,” Acuna said.

But Acuna said that a household beneficiary caught gambling or using the cash grants for other purposes would not be automatically removed from the program unless he or she ignored a third warning by authorities.

“We follow a process. For example, if we have a report, we warn the person concerned. We talk to them. They are delisted after they fail to heed our third warning,” she said in Filipino.

Acuna herself has received a report of an attempt by a household beneficiary to pawn the cash card but said this was immediately stopped by a parent leader assigned to the area.

Target: 3M

Of the two million families registered currently with the program, 1.6 million are receiving conditional cash transfers or an average of more than 100,000 families a month, President Benigno Aquino III said in his 2011 speech before Congress.

“What do we do with them? First, we identified the poorest of the poor, and invested in them, because people are our greatest resource,” Aquino said.

“I am counting on the support of the Filipino people and Congress to expand our Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program. Before the end of 2012, we want to invest in the future of three million poor families,” the President said.

DSWD Secretary Corazon “Dinky” Soliman said even before the end of 2012, the CCT program has served 3,014,586 households, or a little short of the 3,106,979 target for the whole year.

“We have reached 3 million plus families being served by Pantawid, providing education and health grants,’ Soliman told INQUIRER.net.

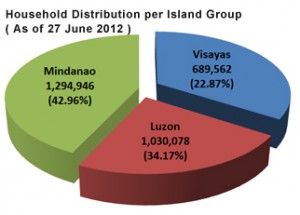

Mindanao has the highest number of beneficiaries totaling 1,294,946 followed by Luzon with 1,030,078 and Visayas with 689,562 beneficiaries, she told the Senate during the oversight committee hearing.

From 321, 380 in 2008, Soliman said the number of beneficiaries rose to 594,356 in 2009; 1,000,138 in 2010; 2, 289, 257 in 2011; and 3, 014, 586 in 2012.

By 2016 or before President Aquino ends his term, she said, the government hoped to cover 4.2 million to 4.6 million beneficiaries.

Program director Rodora Babaran said that from 2008 to 2012, the government spent a total of $1.8 billion.

For the first five months of 2012, Soliman said, the total cash grant released so far was P9.04 billion – P4.63 for health and P4.42 billion for education.

The total allocation for this year was P39.45 billion.

The DSWD chief said they would ask Congress to raise the department’s budget for the CCT program to P44.26 billion in 2013 to be able to serve the 3, 809,769 target household beneficiaries for that year.

Identifying ‘poorest of the poor”

Babaran said the beneficiaries were identified through what they called the “National Household Targeting System.”

“We have a formula to determine whether the household is poor or not. Those listed as poor in every village are subject to validation by the community and by a local verification committee headed by the mayor,’ she explained.

Those considered poor, the Babaran said, were those whose estimated income were below the poverty thresholds determined by the National Statistical Coordination Board.

“For example, we have cleaned up the list, we will be conducting an eligibility check. This means we will see if somebody is pregnant in the household, if there are children between 0 and 14 years old, no income and no one is a government employee,” she said.

The beneficiaries are entitled to a monthly stipend of P500 for health and P300 for education of each child ages 0-14. Only three children of each family, however, may be enrolled in the program.

Soliman said the cash grants were given to beneficiaries every after two months either through ATM, Globe’s remittance service called “G-Remit,’ and through the Philippine Post Office.

Around 1.2 million families receive the cash grants through ATM; 10,000 families through Philpost, while others receive the money through G-remit, she said.

Soliman said they have not received complaints so far but admitted that there were delays or cancelled payments mostly because the beneficiaries live far and Globe, for example, would back out because of the distance or for security reasons.

Beneficiaries who could not withdraw from their ATMs could be due to errors in their data. But the money, Soliman said, remained intact in the bank.

Soliman assured the recipients that the DSWD “never holds the money”.

“The money is always with Land Bank. And from Land Bank, it goes to ATM, to Globe…It never goes thru any of our offices and yet , we are held accountable for it. COA [Commission on Audit] audits us against that,” she said.

Spot checks

To ensure that the cash grants are being used for health and nutrition, and education of the families, the DSWD has set certain conditions like pre and post natal check-up for those who are pregnant; regular growth monitoring, monthly check up, and vaccination for children aged zero to five, and the so called “de-worming” for those six to 14.

“Children who are in day care, elementary or high school should be present 85 percent of the time per month in their schools,” said Babaran.

Parents, she said, were also required to attend regular family development sessions every month.

The DSWD also holds regular “spot” checks and several rounds of impact evaluation on the program to ensure compliance, said Babaran.

“The spot checks are to ensure that our protocols, procedures, and policies are being followed while our impact evaluation is to determine the effects of the program on the beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries for comparison,” said Babaran.

In in its report to the Senate, the DWSD cited its study from November 2011 to December 2011, which showed that the program “has increased the annual incomes of beneficiary households by 18.4 percent and significantly reduced poverty incidence and income gap in the areas covered by the program.”

“Income gap increased by 4.2 percentage points to 27.1 percent from 31.3 percent prior to the implementation of the program. Income inequality in program areas was reduced by 8.0 percent,” the study said.

Goal: ‘Self-reliance’

But Soliman said that each beneficiary family could only receive the cash grants for five years.

Because after the period, she said, the beneficiaries were expected to be “self-reliant” already.

“What do we mean by self-reliant? They have a sustainable source of income, and second, they have a stable shelter and community life, and obviously their children are going to school and eating well,” Soliman said.

By Dec. 31, 2013, she said 286,000 families were expected to have graduated from the program.

But government’s assistance to the beneficiaries, she said, would not stop even after they have left the program.

Soliman said they would either assist the beneficiaries to engage in “community-driven enterprise development by giving them a P10,000 loan, payable in two years without interest, or they would be given “guaranteed employment” depending on their skills.

“We lend P10,000 per family. And that’s non-collateral. No interest. Payable in two years,’ the DSWD chief said.

As early as the third year in the program, Babaran said, the beneficiaries were introduced to “sustainable livelihood, opportunity, and community-driven development approaches.”

In the case of Dades, she was on her fourth year in the program when she availed the P10,000 loan in 2011, which she used to put up a “sari-sari” store. She said the loan was payable in one year and paid P330 a week. But she admitted that she could not pay her obligations in time.

“It’s a big help, especially for my kids’ allowances. Somehow, I am starting to save for the future of my children in the event that we graduate from Pantawid,” she said. Two of her five children are enrolled in the CCT program.

Guaranteed employment, Soliman said, was usually done in partnership with other government agencies.

Soliman said they connected a member of the family to a government program like the “Trabahong Lansangan”of the Department of Public Works and Highways, the re-planting of coconut of the Department of Agriculture, repair or rice terraces in Banawe, among others.

In 2011, she said, around 60,000 to 62,000 household beneficiaries were given livelihood.

To further boost the agency’s livelihood program, Soliman said, the DSWD would ask Congress to raise the agency’s budget from P88 million this year to around P1.2 billion in 2013, on top of its P44.26 billion proposed budget for the CCT program.

Soliman clarified that the Pantawid Program was a “bridge” program toward poverty alleviation and “not a total poverty alleviation measure.”

“A lot of people are saying that it makes the poor dependent on this,

that they would no longer work. I told them, ‘why don’t you try living onP1,400 a month, which you will only get every two months, try living on that and you will die,'” she said.

“That’s why when they say,’the poor become dependent, they don’t work,’ I tell them that the family won’t survive. I would like to tell those who make those comments that they never went through poverty because P1,400 won’t get you too far,” she said.