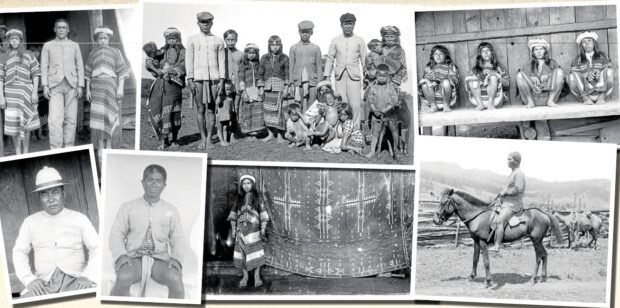

BEFORE BAGUIO | Ibaloys lived a contented life at the turn of the 20th century, building families and tending to cattle before the American colonial government displaced some of them to build and open Baguio City in 1909. This chapter of Ibaloy history was documented through photographs by Insular Government Secretary of the Interior Dean Conant Worcester, which were digitized and given to the city’s Ibaloy families by the University of Michigan. (Photos from the Worcester Collection courtesy of the University of Michigan and the University of the Philippines Baguio)

BAGUIO CITY, Benguet, Philippines — The moment they laid eyes on a photograph taken more than a hundred years ago, descendants of the original Laoyan clan settlers in this city realized that they bore a striking resemblance to the young girl in the portrait.

“Doesn’t she look like auntie?” observed Sharon Pawid, a government employee.

The same girl appeared in many other digitized photographs from the collection of American colonial administrator Dean Conant Worcester which the University of Michigan turned over to Baguio Ibaloy families on Aug. 7 at the Ibaloy Heritage Garden in Burnham Park.

Some of the photographs featured historical figures like Mateo “Kustacio” Carantes, one of the Benguet leaders who joined Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo in the Philippine Revolution. Others were portraits of Ibaloys at their homes or out in pasture lands.

The digitized Worcester photographs numbering over 2,000 images were delivered to the Baguio Ibaloy clans of Laoyan, Palaci, and Cariño, and to the University of the Philippines Baguio as part of Michigan University’s initiative to “decolonize” artifacts and manuscripts.

The university catalog has items that were collected during the twilight years of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, after Spain sold the Philippines to the United States under the Treaty of Paris in 1898.

Depositing these images in the Cordillera was the culmination of a two-year research project by a group of Michigan scholars, many of them of Filipino descent, called “ReConnect-ReCollect.” The project reexamined the university’s colonial-era perspective on Filipino artifacts.

The Philippine collection consists of 4,851 glass plate negatives of archived photographs and 640 lantern slides, 25,000 archaeological artifacts, 617 ethnobotanical specimens, 42 zoological specimens, 1,899 ethnographic objects and even fragments of human skulls.

LINKING GENERATIONS | Ibaloy scholars like former NCIP chair Zenaida Brigida Hamada

Pawid (extreme left) and Brent School official Ursula Daoey (next to Pawid) exchange insights

with Michigan University scholars JimMoss and Filipino-American Diana Bachman about the

Worcester Collection. (Photo by VINCENT CABREZA / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

Embracing culture

To “recontextualize” that era’s offensive worldview about Filipinos, the Michigan team has been integrating and embracing the culture and memories of communities from where these museum items come, said Deirdre dela Cruz, one of the project directors and an associate professor of South East Asian studies and history.

Dela Cruz said Michigan University also wanted to interact with these communities and grant them access to these collections, including US-based Filipinos who wanted to reconnect with their roots but had been unaware that these artifacts “are in their backyard.”

Michigan’s scholars have been tracking and mapping the origins of its artifacts, said Jim Moss, collection manager of his university’s anthropological archaeology museum.

At the university’s Bentley Museum, where some of the Philippine collection are on display, scholars have been rewriting artifact profiles “to provide more context and to not valorize the colonizers,” said museum director Alexis Antracoli.

Dela Cruz said the university collections were generated by the “Michigan Boys,” a term coined for alumni, some of whom took part in the Philippines’ colonization, such as Worcester who served as secretary of the Interior in the Philippine Insular Government.

Worcester also participated in one of the American expeditions that confirmed the suitability of the mountain terrain for America’s only hill station: Baguio City.

To fulfill the promise of a summer capital, “the colonizers lost no time in grabbing the ancestral lands of the original Ibaloy clans and converting the pasture lands, camote (sweet potato) and gabi (taro) patches, expanding ricelands and even their very own homes and residential lots into the Baguio townsite reservation,” said scholar and activist Joanna Cariño.

Sharon Pawid, a Laoyan clan member, says some of the subjects of the colonial era photos have a striking resemblance to their relatives. The Baguio City government has recognized the Ibaloys by designating Feb. 23 as Ibaloy Day. (Photo by EV ESPIRITU / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

Assimilation

Joanna is the granddaughter of Mateo Cariño, who won the landmark 1909 US Supreme Court decision that recognizes “Native Title” in the Philippines. Because of this legal doctrine, the rights and heritage of Ibaloys and all indigenous Filipinos have been enshrined in the 1987 Constitution and protected by the 1997 Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (Republic Act No. 8371).

Mateo sued when his application for titles over Ypit and Lubas was denied because the American military had turned his properties into a garrison that had since become Camp John Hay.

Worcester’s photographs have been perceived as instruments to “support his arguments that the Philippines needed a strong US presence in order to become civilized,” according to the Fall 2011 edition of “Education About Asia” published by the Association for Asian Studies.

Written by Mark Rice, the article “Dean Worcester’s Photographs and American Perceptions of the Philippines” explored Worcester’s 1910 annual report which argued that “allowing Christian Filipinos to assume authority over the non-Christian tribes would result in a violent undoing of the effects of US colonial policy.”

He said the report used “carefully selected images showing what he presented as the benefits of US colonialism … [among them photographs of] Igorot girls working on a modern weaving loom, a schoolhouse built for Igorot boys, [and] Ifugao constabulary soldiers standing in formation.”

“One of the most famous sets of photographs from his archive [is] a three-part sequence of images that claims to show the transformation of a Bontoc Igorot man from savagery to civilization because of enlistment in the Philippine Constabulary,” wrote Rice.

The Baguio City government has recognized the Ibaloys by designating Feb. 23 as Ibaloy Day. (Photo by EV ESPIRITU / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

Communal

But for the Ibaloys who saw Worcester’s collection for the first time, the experience was more “communal” than political.

“We believe we know everyone in those photographs,” some of which were labeled simply as Igorot boy or girl, said teacher Ursula Daoey, a Laoyan clan member.

Some Ibaloys recognized another revolutionary in one of the photographs: Mateo’s son, Sioco Cariño. One of the first “presidente” of Benguet’s capital town of La Trinidad, Clemente Laoyan, is pictured on horseback. Presidente are municipal district presidents who were equivalent to mayors in 1900.

Coming face-to-face with one’s relatives from a hundred years ago can be startling, said Zenaida Brigida Hamada Pawid, former chair of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) during a roundtable conference with the Michigan scholars the following day.

“Even without PhDs (academic doctorates),” Cordillera communities have been documenting and writing their own stories for decades and “have come up with what is truly their own history,” Pawid said.

The Worcester images add texture to those stories by revealing “how Baguio grew,” and showing the children and grandchildren of the Ibaloys in the photographs “how they really looked.”