Disasters in PH: Experts say there’s nothing natural about it

MANILA, Philippines—In the Philippines, the term “natural disasters” is commonly used to describe calamities—typhoons and tropical storms among them—but experts stressed that there is no such thing as natural in disasters.

In a country where an average of 18 to 20 typhoons are projected to hit per year, the term natural disasters have been widely used to describe such climatic events—which also includes heatwave, drought, storm surges, and flooding.

Throughout the years, various literature and news reports have used the phrase. In his recent State of the Nation Address, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. likewise used it in detailing the administration’s disaster response.

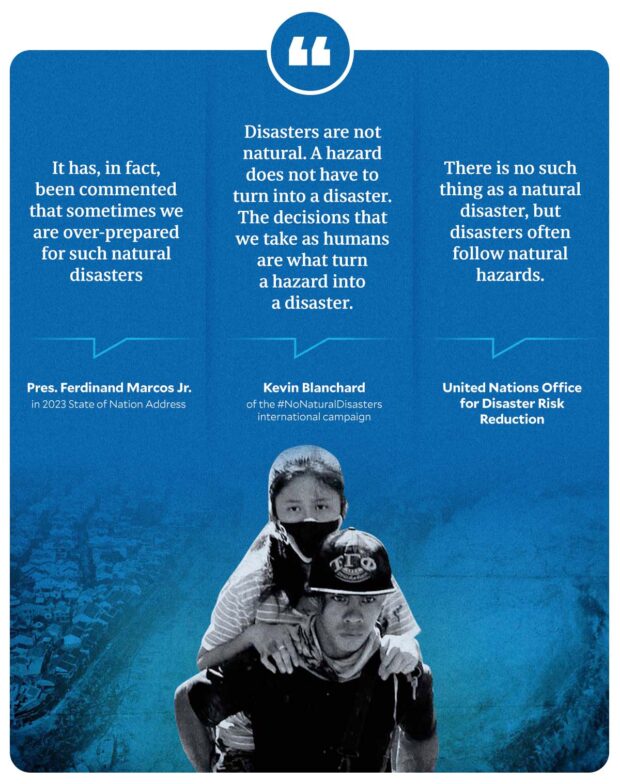

“We have learned many painful lessons from past disasters but we continue to be alert and prepared in our disaster response. It has, in fact, been commented that sometimes we are over-prepared for such natural disasters,” Marcos said.

“Our evacuation centers are being upgraded to withstand the greater forces of the new normal of extreme weather, as well as other natural and man-made disasters,” he added.

Article continues after this advertisementHowever, several experts have called for a stop to using the phrase natural disasters. They also warned of the possible danger of using the term, which a previous study described as a “misnomer.”

Article continues after this advertisementNo such thing as ‘natural’ disasters

According to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), “there is no such thing as a natural disaster.” However, it believes that disasters often follow natural hazards.

The #NoNaturalDisasters—an international campaign that aims to change the way organizations, politicians, media, and people in positions of power talk about disasters—stressed that the widely-used term is incorrect and misleading.

“Disasters are not natural. A hazard does not have to turn into a disaster. The decisions that we take as humans are what turn a hazard into a disaster,” said Kevin Blanchard of the #NoNaturalDisasters international campaign in a previous statement.

According to the campaign, several experts have been questioning the use of the term since 1756.

In a previously published article, Mami Mizutori, the special representative of the United Nations secretary-general for disaster risk reduction, said efforts to replace the term natural disasters have been underway since the end of the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction in the 1990s.

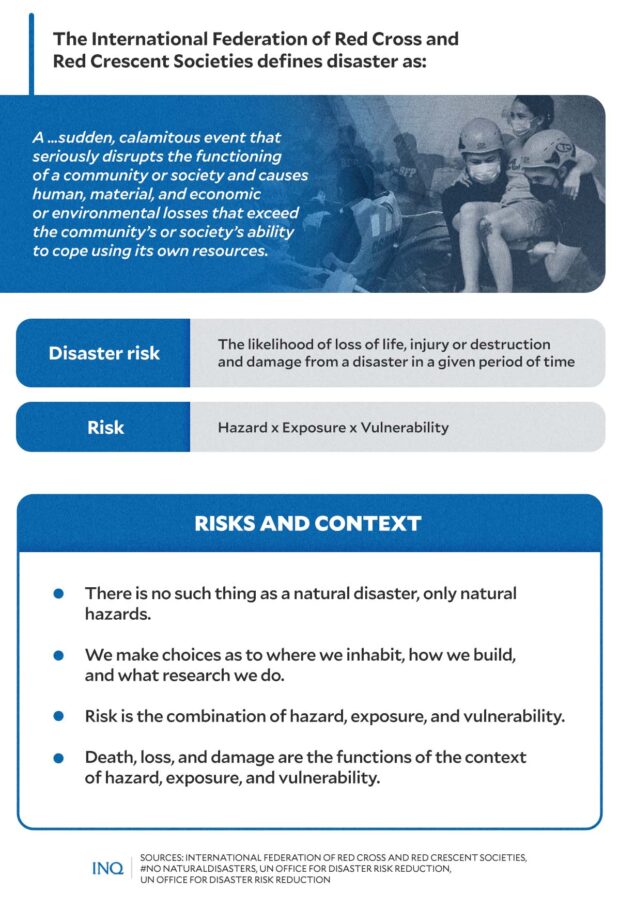

To understand why the term natural disaster is incorrect and misleading, the campaign cited the most widely used definition of a disaster that has been developed by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). It states that a disaster is:

“A …sudden, calamitous event that seriously disrupts the functioning of a community or society and causes human, material, and economic or environmental losses that exceed the community’s or society’s ability to cope using its own resources.”

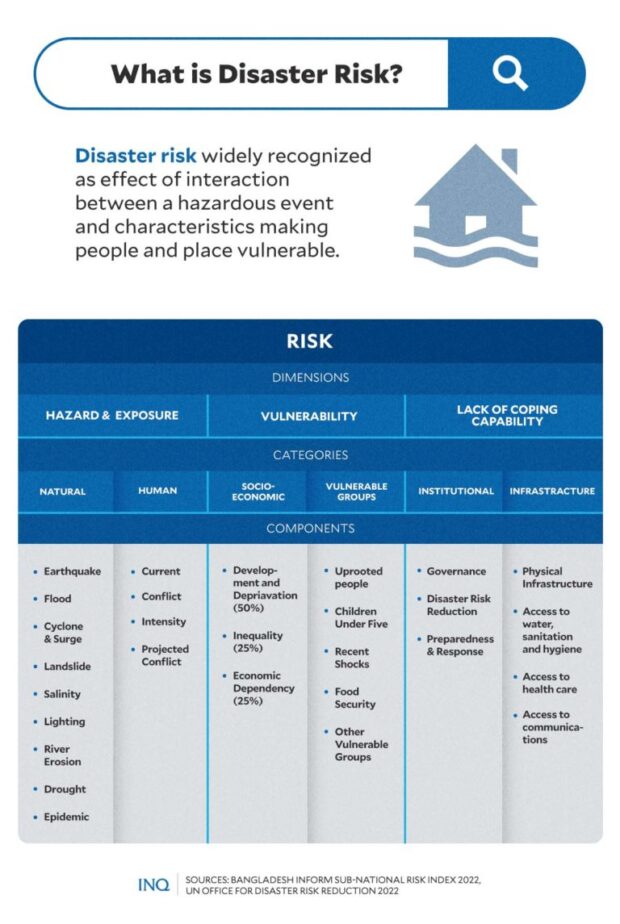

According to the international campaign, this means that a hazard—defined as the dangerous process, phenomenon, or human activity that may cause loss of life, injury, or other impacts—can only become a disaster once it affects society or communities.

“A hazard is natural, disasters are not. For instance, earthquakes, typhoons, and volcanoes are natural processes that have occurred for millions of years and are not controlled by humans,” the campaign said.

“A hazard will only become a disaster should it impact the workings of a society or community. As such, a disaster can only happen where a society or community exists,” it added.

“That society has made (often historic and often made by elites in positions of power) economic, planning and other socio-economic decisions that will alter their vulnerability to the hazard and change how the hazard impacts them,” the campaign said.

The international campaign underscored that using the word natural to describe disasters sets off the idea that the event would occur anyway despite decisions taken by humans and that there is not much humans can do to alter it “due to its natural origins.”

It added that the term natural disaster might feed an idea that disaster losses from nature were an “act of God,” and further allows powerful decision-makers to not take responsibility for allowing or forcing people to live in vulnerable conditions.

“[T]o say a disaster is natural is wrong. What’s worse, it misleads people to think the devastating results are inevitable, out of our control, and are simply part of a natural process,” the international campaign said.

“Hazards (earthquakes, hurricanes, flooding) are inevitable but the impact they have on society is not.”

Experts then suggest simply using the term disaster.

One-off event, Filipino resilience

Although the Philippines has made strides in disaster risk and preparedness since the creation of NDRRMC after Republic Act (RA) No. 10121 became law, some experts said there are still many things to be considered and issues to be addressed.

Among these issues is the way the country and its government see or frame disasters. In a previous interview with INQUIRER.net, Timothy James Cipriano—a geographer and professor whose research focuses on hazards and disasters—said disasters are often framed as a one-off event.

“We see disasters as a one-off event that happens, [and then] after that, we recover. Like once a disaster ended, we [automatically] go back to our [day-to-day] lives. But in fact, there are what we call compounding hazards that also lead to complex disasters,” Cipirano said.

“I think it is crucial [to examine] how we see disasters. Do we see disasters as a one-off event, or do we see disasters as something that is lingering and is affecting our lives for a longer period,” he added.

READ: In search for better emergency response, PH told there’s no such thing as natural disaster

Another issue, which experts have time and again criticized, is the tendency to romanticize Filipino resilience whenever disasters and calamities hit and devastate the country.

Filipino resilience has been often depicted through photos and videos of people smiling and laughing amid floodwaters “as if to show that, despite the hardships, everything’s all right.”

“At the individual level, there’s nothing wrong with this narrative: It is certainly true that Filipinos manage to smile even in the direst of circumstances. But to equate smiling faces with resilience, and ending the story at that, is problematic for a number of reasons,” said medical anthropologist Dr. Gideon Lasco in an opinion piece published on INQUIRER.net.

READ: Romanticizing resilience

For Dr. Emma Porio, professor emeritus and project leader and principal investigator of the Coastal Cities at Risk in the Philippines (CCRPH), resilience should refer to everyday action and efforts to prepare for disasters and calamities.

“Resilience is everyday action prepared. It’s the ability to absorb the shock, to resist the effects of the shock, and to transform our ways of doing things that we can proactively respond better,” she told reporters.

“I feel that we have focused really on evacuating and all that stuff but I think we have to build the capacities of everyone [to respond effectively to the impacts of disasters],” she continued.

Sen. Loren Legarda stressed the need to pass and enact laws since there is a limit to Filipino resilience.

“I would like to see a time when there is no time for resilience because we did it right the first time,” the senator said.

Addressing, reducing disaster risk

Some environmental groups and organizations reacted to the President’s second Sona, particularly the absence of mention of crucial environmental issues and the specific steps to address the climate crisis.

Greenpeace Philippines also reacted to what Marcos Jr. said about the country being “over-prepared” for disasters.

“The fact that [Mr. Marcos] was proud of the country being ‘overprepared’ in response to natural disasters shows a lack of awareness of the reality on the ground,” the organization said.

“When people and the local economies suffer after every major typhoon, that is not preparedness. Data also shows that [many] of our coastal cities stand to lose billions [of pesos] from sea-level rise. We have yet to see a clear government plan to address these climate impacts,” it added.

READ: Green groups on Sona: No hard steps vs environmental issues

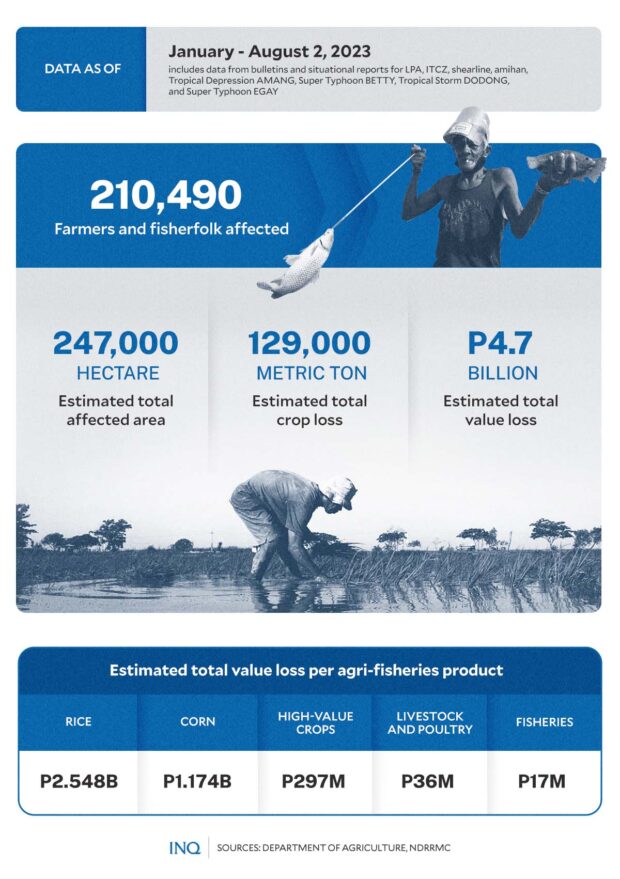

Data gathered from the Department of Agriculture (DA) and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) showed that so far, over 200,000 hectares of land used for agriculture has been affected by extreme weather conditions that hit the country since January of this year.

This equates to an estimated P4 billion loss in agriculture and more than 128,000 metric tons of crop volume loss.

In its latest situational report released on August 3, the NDRRMC revealed that Typhoon Egay (international name: Doksuri) and the southwest monsoon (habagat) affected nearly 3 million people in the country.

READ: NDRRMC: Nearly 3M affected by Typhoon Egay, southwest monsoon as of August 3

According to the UNDRR, countries and their governments need to manage risks and not just disasters.

“Although DRM includes disaster preparedness and response activities, it is about much more than managing disasters. Successful DRR results from the combination of top-down, institutional changes and strategies, with bottom-up, local and community-based approaches,” the UN agency explained.

“Approaches need to address the different layers of risk (from intensive to extensive risk), underlying risk drivers, as well as be tailored to local contexts,” it added.

UNDRR likewise stressed that much can be done to reduce the exposure and vulnerability of populations living in areas where natural hazards occur, whether frequently or infrequently.

TSB