When those who feed the nation are the poorest: Farmers, fisherfolk in deepest poverty pit

MANILA, Philippines—As an agricultural and archipelagic country, the Philippines has always regarded farmers and fisherfolk as its backbone, especially with millions of Filipinos depending on them for food.

Out of the 47.35 million employed Filipinos in January 2023, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) said 22.2 percent were in agriculture—87.3 percent in agriculture and forestry and 12.7 percent in fishing and aquaculture.

READ: Fisherfolk, farmers, rural communities poorest in 2021 — PSA

But “ironically,” according to the Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region (FFTC-AP), Filipinos employed as farmers and fishermen remain to be the poorest in the Philippines.

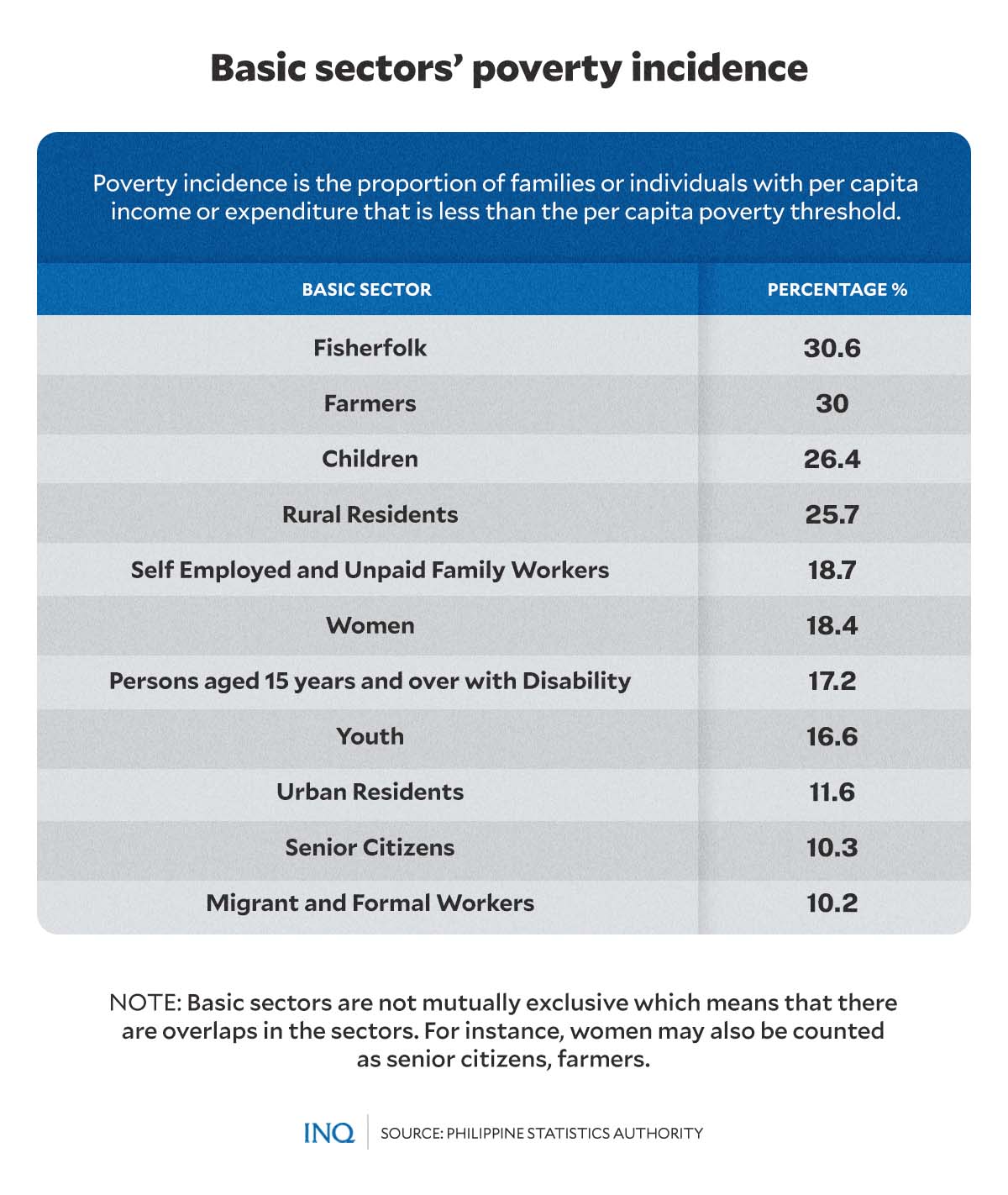

As revealed by the PSA last week, fisherfolk and farmers were still the poorest among the basic sectors in 2021, having a poverty incidence of 30.6 percent and 30 percent, respectively.

“Significant increases” in poverty incidence were seen, the highest being among fisherfolk with an increase of 4.4 percent, children (2.5 percent), persons aged 15 years and over with disability (2.5 percent), and individuals residing in urban areas (2.3 percent).

Article continues after this advertisementThe only basic class which had an improvement from 2018 to 2021 was farmers with a “significant reduction” in poverty incidence of negative 1.6 percent, the PSA said last Friday (March 24).

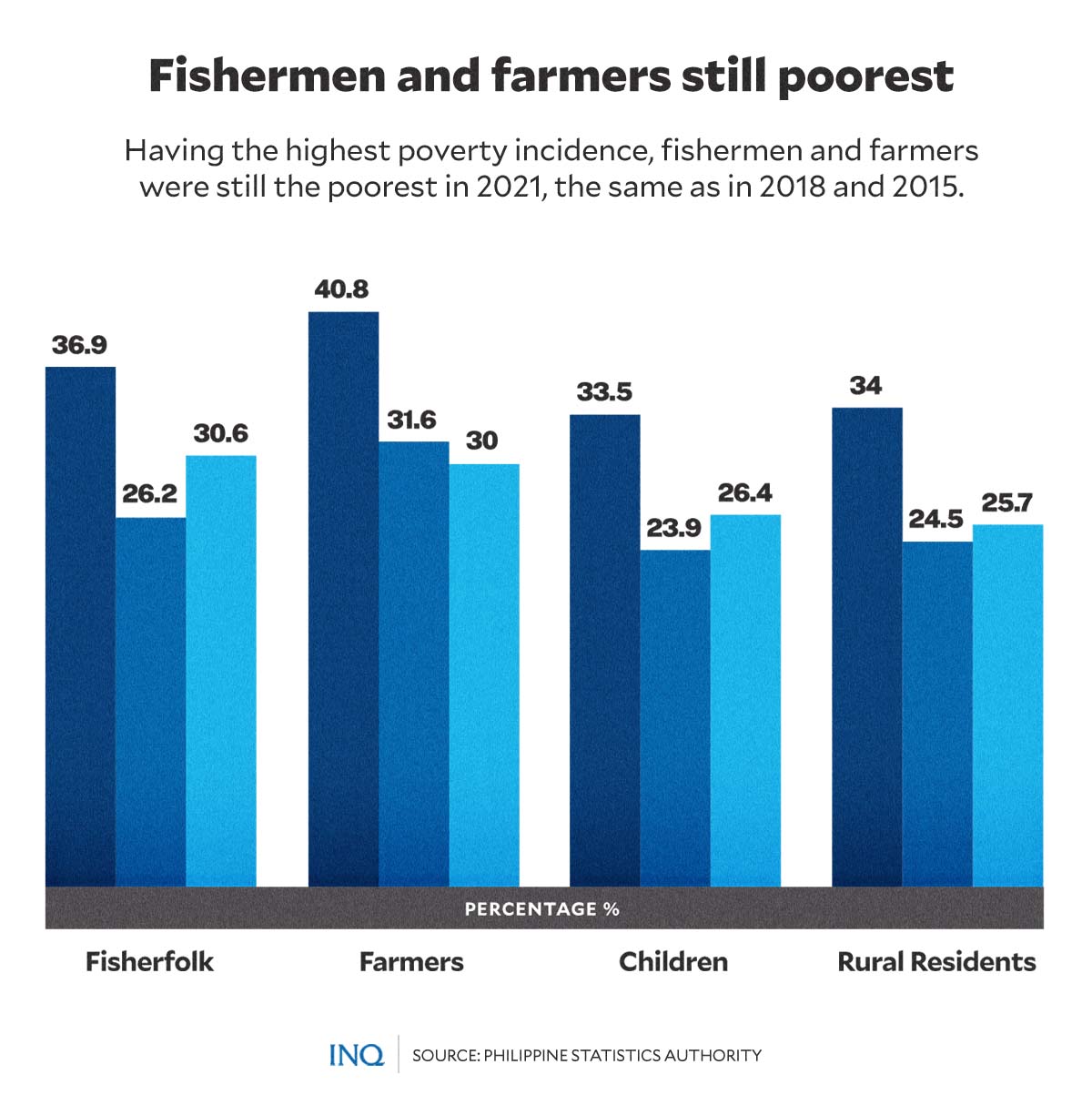

Article continues after this advertisementBack in 2015 and 2018, these sectors likewise registered the highest poverty incidence, with fisherfolk having a rate of 36.9 percent and 26.2 percent, while farmers had 40.8 percent and 31.6 percent.

So why is it that the people responsible for producing everyday food for millions of Filipinos continue to be the poorest, with most living below the poverty threshold, or the minimum income that a family of five needs to meet basic food and non-food needs?

Landlessness, rich’s control

According to Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas chairperson Rafael Mariano, the poor condition of Filipino peasants in farming and fisheries is one of the direct results of centuries-old landlessness.

Mariano told INQUIRER.net that “large-scale land deals and acquisitions [and] land grabs led by corporations have dispossessed and displaced farmers from the land they till.”

“Millions of hectares of land planted with staples, grains, and food crops, as well as indigenous lands, and public lands, were grabbed and converted into plantations, extractive mining projects, and farms devoted to export cash crops,” he said.

Mariano said “profits and more income also keep pouring into the pockets of the few as most of the peasants and their families endure worsening landlessness and land grabs amid a worsening global food and economic crises.”

READ: Day of the Landless: The failed promises of land reform in PH

Then farmers who assert land rights, he said, “face attacks either from local landlords, big corporations, and even the government,” stressing that violence against farmers and fishermen take place everyday.

Mariano, who was once agrarian reform secretary, likewise shared that in the past years, his group has witnessed the increasing dominance of corporations in the agriculture and food sector.

“We have seen mega-mergers and multi-billion deals between companies that have control over the global seed market, agrochemicals, fertilizers, farm equipment and machinery, and the entire chain of food production,” he said.

He said “conglomerates are now among the world’s largest food producers. They have made a profitable empire while trampling upon the lives and livelihoods of farming families and rural people.”

Millions of Filipinos living in poverty

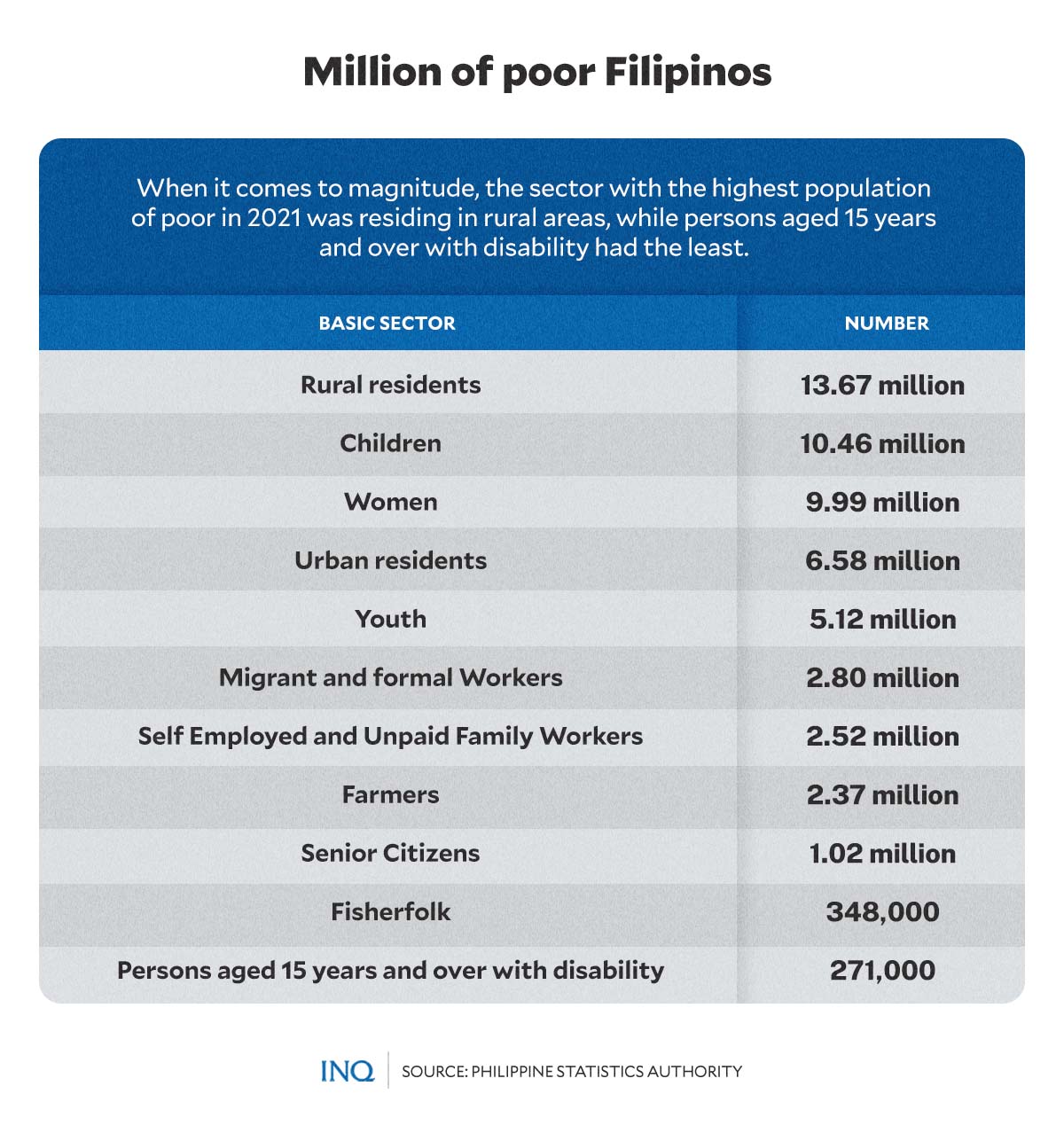

When it comes to the magnitude of poor population, the basic sectors with the highest number of poor in 2021 were rural residents (13.67 million), children (10.46 million, women (9.99 million), urban residents (6.58 million), and youth (5.12 million).

The basic sector with the least number of poor were persons aged 15 years and over with disability (271,000), fisherfolk (348,000), senior citizens (1.02 million), farmers (2.37 million), and self-employed and unpaid family workers (2.52 million).

As explained by the PSA, “poverty is a characteristic of the family” so the total family income is divided by the family size to get the per capita income and this is compared with the poverty threshold to determine if the family is poor or not.

“Thus, if a family has been classified as poor, then all members of the family will be counted as poor,” it said, stressing that, a family cannot have poor and non-poor members. “Either all members are poor or all members are non-poor.”

Last year, it said 19.99 million Filipinos (3.50 million families) were considered poor in 2021 as poverty incidence rose to 18.1 percent from 16.7 percent—P17.67 million (3 million families)—in 2018.

The PSA said the poverty threshold, the minimum income a family of five needs to meet basic food and non-food requirements, was P12,030, 11.8 percent higher than P10,756 in 2018.

READ: PH poverty: You’re not poor if you spend more than P18.62 per meal

Gov’t neglect

As stressed by the FFTC-AP “poverty among agricultural workers is mainly attributed to the lack of enough attention to the agricultural sector—one of the greatest blunders any developing country such as the Philippines could do.”

It said “there have been weak policies and programs, excessive import reliance, and corruption,” adding that despite the 11 percent contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019, investment in the sector was only 4 percent of the national budget.

“Adding to this is the very low investment for research and development, averaging to only about 1 percent of the total national budget. This is far below the investment for research and development (R&D) budget for developing countries which is 3 percent.”

“With such dismal funding, the Philippines lags behind its neighboring countries in terms of allocation for R&D. Another concern is the bias of government policies on increasing yield without much consideration on the well-being of farmers and their families,” said FFTC-AP.

Last year, the think tank Ibon Foundation said farmers continue to suffer from government neglect of the agriculture sector, saying that the sector contributes only an average of 9.8 percent of GDP every year (2017 to 2021).

It only registered an average of 1.2 percent yearly growth, which is less than one-third of the 3.8 percent historical average since the end of World War II. It added that 1.8 million agricultural jobs were lost from July 2016 to January 2022.

Based on PSA data, industry and services posted positive growths in the last quarter of 2022 with 4.8 percent and 9.8 percent, respectively. However, agriculture, forestry, and fishing posted a contraction of -0.3 percent.

As the Pambansang Lakas ng Kilusang Mamamalakaya (Pamalakaya) said, “we can only blame the misery of our rural sectors on the negligence of the previous administrations to address the needs of the fisherfolk.”

What tomorrow holds for agriculture

The FFTC-AP said “suffice it to say, an ordinary Filipino farmer can be characterized by poor living standard, small landholding, low education, vulnerability to physical and economic risks, and zero savings or worse, indebtedness.”

“The association of agriculture to poverty already drove many children of agricultural workers toward finding more lucrative employment opportunities in urban areas,” it said.

The FFTC-AP said this resulted in low appreciation for agriculture by the young generation and depleting human resource in the pool of agricultural labor force.

As college student Johanna Trisha Cinco said when asked in the search for Queen Isabela 2023 about how she can encourage young people to choose a career in agriculture, “I think it’s time for us to stop burdening the society to go to jobs that don’t benefit them.”

“Instead, we should burden the system to create a more sustainable position for farmers and make farming a good job for the people.”

“And once we do that, once the government does its job, that’s when millennials will choose to be farmers because by then, it’s a profession that will feed their family and it’s a profession that will give them a sustainable life,” she said.