COVID worsens ‘largest backslide’ in child vaccinations in 30 years

Children get free vaccine against measles-rubella and polio in Quezon City. FILE PHOTO/NIÑO JESUS ORBETA/PHILIPPINE DAILY INQUIRER

(First of two parts)

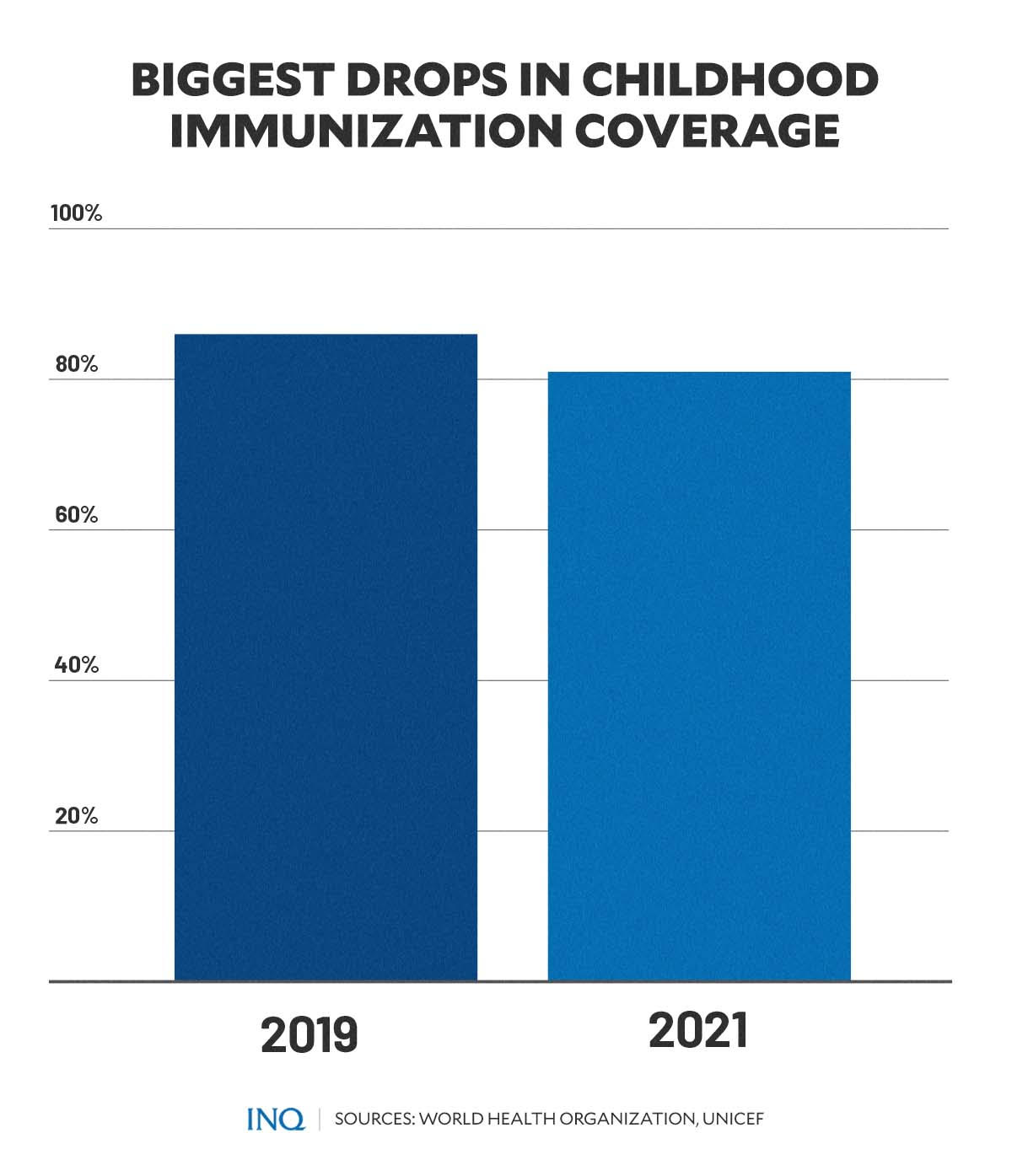

MANILA, Philippines—Last year, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the largest sustained decline in childhood vaccinations in approximately 30 years—with millions of children across the globe missing doses of lifesaving vaccines for preventable but deadly diseases.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF recently released data showing the huge decline in immunization coverage for children worldwide.

At least 25 million children under the age of 1 year were unable to receive basic vaccines—the highest number recorded since 2009. The number of completely unvaccinated children increased by 5 million in 2021 compared to numbers recorded in 2019.

“This is a red alert for child health. We are witnessing the largest sustained drop in childhood immunization in a generation. The consequences will be measured in lives,” said Catherine Russell, UNICEF Executive Director.

Article continues after this advertisement“While a pandemic hangover was expected last year as a result of COVID-19 disruptions and lockdowns, what we are seeing now is a continued decline,” Russell said.

Article continues after this advertisement“COVID-19 is not an excuse. We need immunization catch-ups for the missing millions, or we will inevitably witness more outbreaks, more sick children, and greater pressure on already strained health systems.”

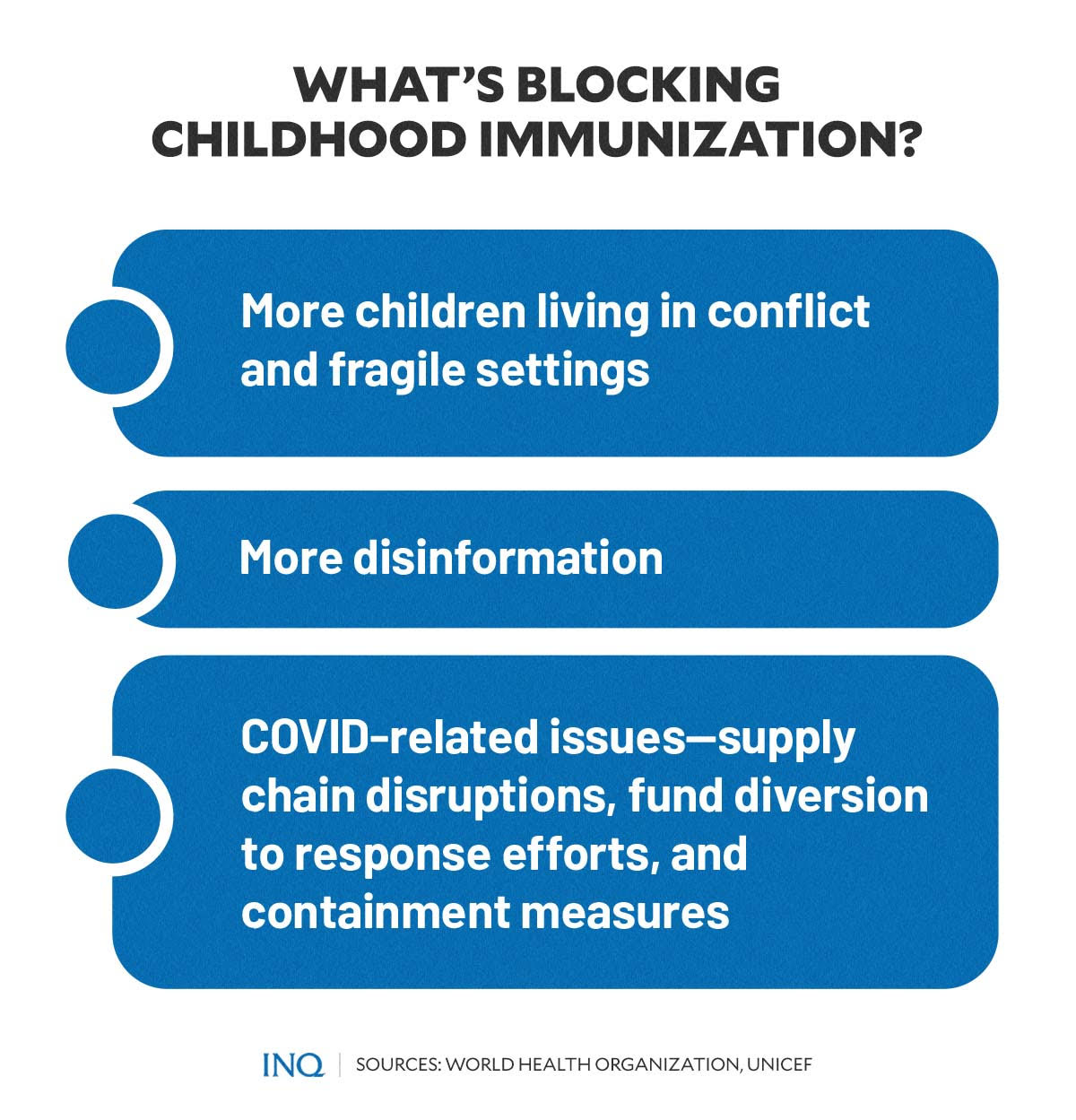

WHO and UNICEF attributed the decline in childhood vaccinations to several factors, including an increase in the number of children living in conflict and fragile settings—where immunization access is often difficult or highly risky.

Increased misinformation plus COVID-related issues (service and supply disruptions, resource diversion to response efforts, and containment measures) were also listed as reasons for limited immunization service access and availability in many countries.

“Planning and tackling COVID-19 should also go hand-in-hand with vaccinating for killer diseases like measles, pneumonia, and diarrhea,” WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said.

“It’s not a question of either/or, it’s possible to do both”.

The latest immunization coverage data showed that the Philippines was among the countries with the highest number of children who did not receive a single dose of at least one of the most important childhood vaccines.

How many shots do children need?

Vaccines protect children from life-threatening diseases.

However, UNICEF Philippines previously emphasized that “for routine vaccines to be effective, children need to complete the required doses according to schedule from the time they are born until they are one year old.”

Additional or booster doses during supplementary or catch-up vaccination campaigns announced by the Department of Health (DOH) should also be completed as the children grow older.

“Routine immunization coverage among children must be at least 95 percent. Routine vaccines are provided by the government for free in public health centers and facilities,” said UNICEF Philippines.

Among the required vaccines for routine immunization of Filipino children include:

- BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin ) vaccine: offers protection from Tuberculosis (Tb); given to newborn children

- Hepatitis B vaccine: offers protection from Hepatitis B; given at birth

- Pentavalent (DTP-HepB-Hib) vaccine: offers protection from Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus, Influenza B, and Hepatitis B; given to newborn children at 6, 10, and 14 weeks

- Oral polio vaccine (OPV): offers protection from Poliovirus; given at 6, 10, and 14 weeks

- Inactivated polio vaccine (IPV): offers protection from Poliovirus; given at 14 weeks

- Pneumococcal vaccine (PCV): offers protection from Pneumonia and Meningitis; given at 6, 10, and 14 weeks

- Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine: offers protection from MMR; given to 9-month-old and 1-year-old children

US-based Stanford Medicine also noted that booster shots for DPT, IVP MMR, and chickenpox are required for children from age 4 to 6. Children should also receive a yearly flu shot after age 6 months.

Filipino children missing doses

The latest data released by WHO and UNICEF showed that the global percentage of children who received three doses of vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP3)—“a marker for immunization coverage within and across countries”—dropped from 86 percent in 2019 to 81 percent in 2021.

“As a result, 25 million children missed out on one or more doses of DTP through routine immunization services in 2021 alone,” WHO and UNICEF said.

“This is 2 million more than those who missed out in 2020 and 6 million more than in 2019, highlighting the growing number of children at risk from devastating but preventable diseases.”

Around 18 million out of 25 million children worldwide, who did not receive a single dose of DTP in 2021, were from low-and middle-income countries, including India, Nigeria, Indonesia, Ethiopia, and the Philippines.

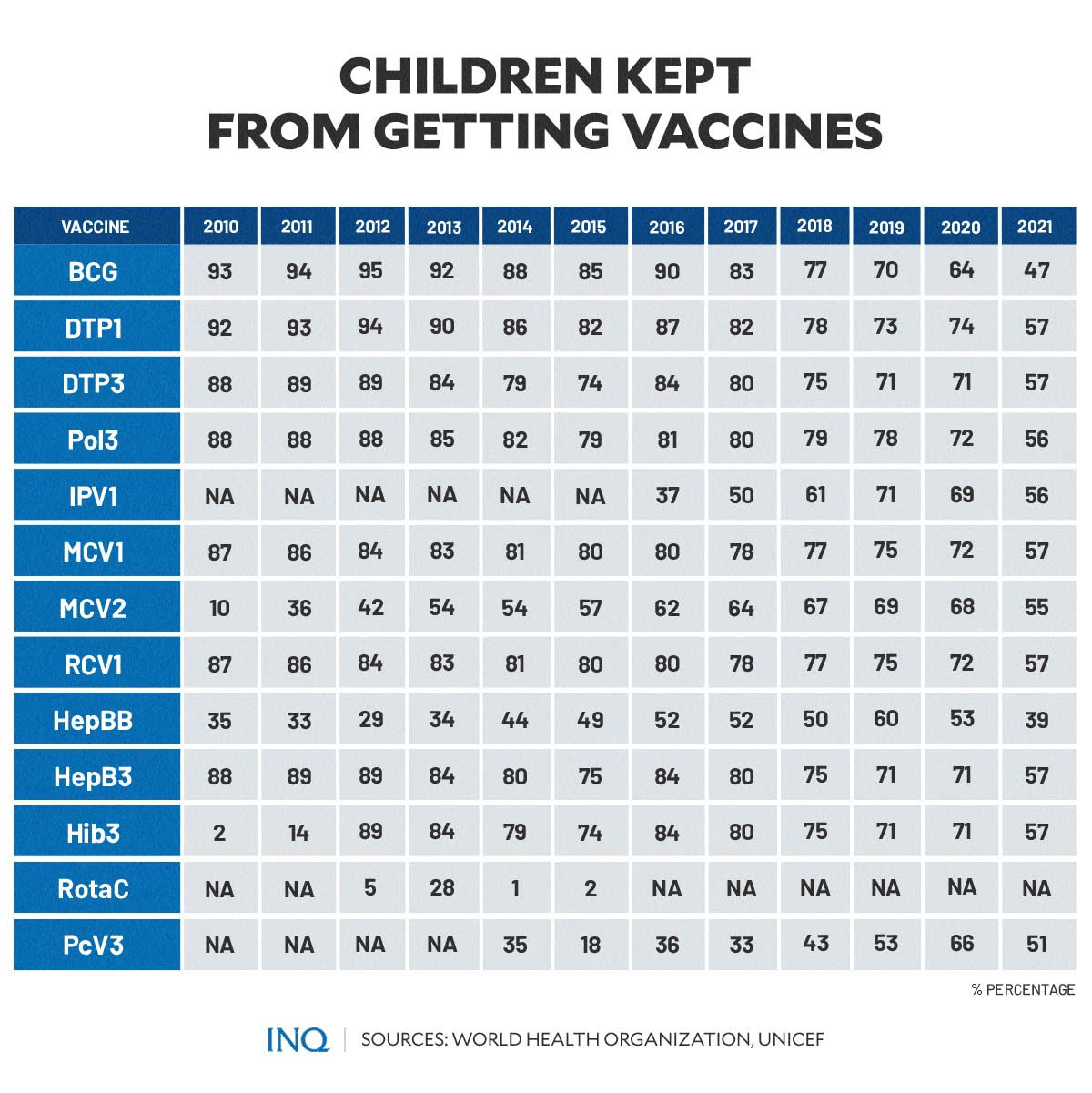

In the Philippines, the percentage of children who received the first dose of diphtheria and tetanus toxoid with pertussis-containing vaccine (DTP1) fell from 92 percent in 2010 to 57 percent in 2021.

In 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the immunization coverage for the DTP1 vaccine among Filipino children was 74 percent. The highest coverage was recorded in 2012 with 94 percent.

According to the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society of the Philippines, children are required to have a total of 5 doses of the DTP vaccine until they reach the age of 6.

Similar to figures reported for DTP1 coverage in the country, the number of children who were inoculated with the third dose of DTP vaccine (DTP3) dropped from 88 percent in 2010 to 57 percent last year.

In 2020 and 2019, the coverage for that vaccine dose was both 71 percent. The highest coverage was reported in 2011 and 2012, both of which reached 89 percent.

Based on the surveillance report of the DOH Epidemiology Bureau-Public Health Surveillance Division, from January 1 to August 14, 2021, there were 13 cases and 7 deaths caused by neonatal tetanus—tetanus cases among newborn children.

Aside from the DTP vaccine, the immunization coverage for other required pediatric vaccines in the country also suffered a huge drop in 2021. These were:

BCG vaccine

The estimated percentage of Filipino children who got their BCG vaccine dose against TB declined from 93 percent in 2010—the highest coverage recorded—to 47 percent in 2021.

In 2020, WHO reported that the Philippines has the highest TB incidence rate in Asia, with 554 cases for every 100,000 Filipinos. During the same year, only 64 percent of Filipino children were vaccinated with BCG.

TB, according to UNICEF Philippines, is an infection that usually attacks the lungs. But in infants and younger children, it can affect other organs like the brain. A severe case of TB could also cause serious complications or death.

Pol3, IPV

On September 19, 2019, the DOH announced a polio outbreak in the Philippines—after 19 years of being polio-free.

At that time, 78 percent of children in the country received their third dose of polio-containing vaccine (Pol3), either oral or inactivated polio vaccine (IVP). Meanwhile, 71 percent received at least one dose of IVP.

The numbers continued to decline in 2021, with only 56 percent of Filipino children who got Pol3 and 56 percent who had their first dose or at least one dose of IVP.

Fortunately, on June 3, 2021, the DOH officially concluded the polio outbreak response in the country.

The health department noted that the decision was made “as the virus has not been detected in a child or in the environment in the past 16 months and is a result of comprehensive outbreak response actions including intensified immunization and surveillance activities in affected areas of the country.”

MCV 1 and 3

In 2019, DOH declared a measles outbreak. From January 1 to March 1 that year, a total of 13,723 persons in the country had measles, and 215 of them died.

WHO has cited the country’s low immunization coverage in several communities as among the reasons the Philippines had a measles outbreak two years ago.

READ: Measles outbreak: 215 deaths, over 13K affected from Jan 1 to Feb 26 – DOH

In February last year, the health department resumed its supplemental immunization drive against rubella (otherwise known as German measles), tigdas, and polio, offering free MR vaccine (measles and rubella virus vaccine live) to children from 9 months old to 5 years old and MR vaccine with OPV (oral poliovirus vaccine) drops to newborn babies as well as kids from 1 year old to 5 years old.

READ: EXPLAINER: Why children must be vaccinated vs rubella, tigdas, polio

However, WHO and UNICEF’s latest data showed that the percentage of Filipino infants who received their first and second dose of measles-containing vaccine continued to decrease compared to data recorded in 2010 and 2019.

In 2010, 87 percent of infants were able to get their first MCV dose. In 2019, despite the government’s supplemental immunization drive, only 75 percent were initially vaccinated against measles.

The 2010 percentage of infants who had their third dose of MCV was only 10 percent. It increased in 2019 to 69 percent.

However, in 2021, the figures went down to only 57 percent of infants who were vaccinated with the first dose of MCV, while only 55 percent received their second dose.

RCV1

The percentage of surviving infants who received the first dose of rubella-containing vaccine likewise dropped from 87 percent in 2010 to 57 percent in 2021.

WHO and UNICEF, however, explained that the estimated average for the RCV1 data was based on the estimates of coverage for the dose of measles-containing vaccine, which corresponds to the first measles-rubella combination vaccine.

“Nationally reported coverage of RCV is not taken into consideration nor are the data represented in the accompanying graph and data table.”

HepBB, HepB3 vaccine

When caught as an infant, the Hepatitis B virus—a dangerous liver infection—often shows no symptoms for decades. UNICEF said it could develop into cirrhosis and liver cancer later in life.

Children below the age of 6, who become infected with the virus, are the most likely to develop liver cirrhosis.

READ: Liver cancer, diseases: A silent epidemic in PH

The latest WHO-UNICEF data showed that the percentage of newborns who received a dose of hepatitis B vaccine (HepBB) within 24 hours of delivery was 39 percent in 2021.

It was slightly higher than 35 percent in 2010. The highest recorded number of infants who were given HepBB vaccines was in 2019, accounting for 60 percent.

“Estimates of hepatitis B birth dose coverage are produced only for countries with a universal birth dose policy,” the WHO and UNICEF clarified.

“Estimates are not produced for countries that recommend a birth dose to infants born to HepB virus-infected mothers only or where there is insufficient information to determine whether vaccination is within 24 hours of birth,” it added.

Meanwhile, the percentage of surviving infants who received the third dose of hepatitis B-containing vaccine (HepB3) following the birth dose was 57 percent in 2021—significantly lower than the 88 percent in 2010 and 89 percent recorded both in 2011 and 2012.

Hib3 vaccine

Haemophilus influenzae type b, according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), usually affects children under 5 years of age, although it can also affect adults with certain medical conditions.

This can cause many different kinds of infections. The bacteria can cause mild illness, such as ear infections or bronchitis, or they can cause severe illness, such as infections of the blood. It can also lead to:

- pneumonia;

- severe swelling in the throat, making it difficult to breathe;

- infections of the blood, joints, bones, and covering of the heart; and

death

In the Philippines, the percentage of infants who received the third dose of Haemophilus influenzae type b-containing vaccine was 57 percent in 2021—lower than the 89 percent in 2012 and 71 percent recorded in 2019 and 2020 during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

RotaC vaccine

Rotavirus, which spreads easily among infants and young children, can cause severe watery diarrhea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain.

The number of rotavirus cases among newborns and younger children in the Philippines went up from 3,220 in 2015 to 4,305 in 2019, according to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

The percentage of surviving infants in the country who received the final recommended dose of the rotavirus vaccine—which can be either the second or the third dose depending on the vaccine—from 2016 to 2021 was not available according to WHO and UNICEF.

PcV3

Based on WHO and UNICEF’s latest report, the percentage of surviving infants who received the third dose of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the Philippines by 2021 was 51 percent.

Although the figures were higher than the 35 percent in 2014—the earliest data recorded for PcV3 vaccination in the country—the 2021 numbers were lower than the 66 percent in 2020.

“In countries where the national schedule recommends two doses during infancy and a booster dose at 12 months or later based on the epidemiology of disease in the country, coverage estimates may reflect the percentage of surviving infants who received two doses of PcV prior to the 1st birthday,” WHO and UNICEF noted.

Pneumococcal diseases, such as pneumonia and meningitis, UNICEF Philippines explained, are a common cause of sickness and death worldwide, especially among young children under 2 years old.

(Next: Impact on malnourished children of vaccination declines)