Pampanga churches rise from nature’s fury

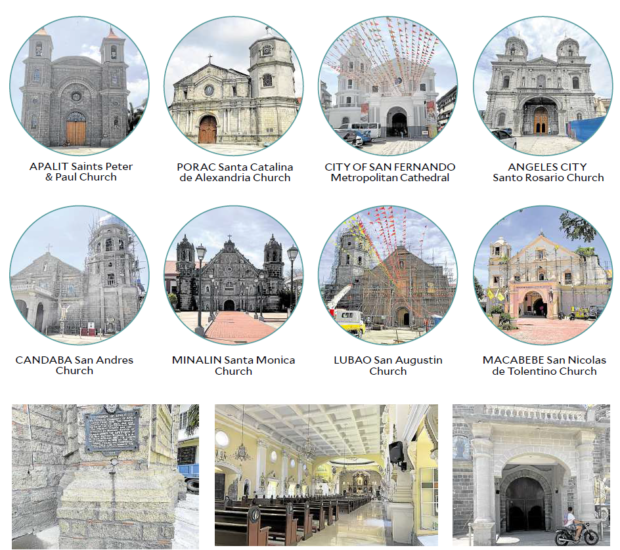

OLD AND NEW | The Spanish colonial era churches (from left) of Saints Peter and Paul in Apalit, San Nicolas de Tolentino in Macabebe and San Andres in Candaba undergo repair or restoration to fill big cracks, replace fallen rocks and raise floors due to deterioration before and after the 6.1-magnitude earthquake that jolted Pampanga in 2019. (Photos by TONETTE OREJAS / Inquirer Central Luzon)

PORAC, Pampanga, Philippines — As she sold snacks from her store on May 20, Virginia Toledo glanced across the Santa Catalina de Alexandria Parish, which a 6.1-magnitude earthquake severely damaged on April 22, 2019.

At one point, the 80-year-old grandmother told devotees she was grateful its campanario (belfry) was rebuilt. It is where bells are rung to invite Catholics to holy Masses, warn of disasters, announce deaths or express solidarity with good causes.

Toledo has vivid memories of the disaster in their place of worship.

“The ground shook around 5 p.m. I called out to the workers preparing for Holy Week events,” she said in Kapampangan.

She added: “Run out to the street, I shouted at them. Concrete slabs were falling. The belfry swayed to the left and then collapsed.”

Guided by priests, the reconstruction committee restored the structure to its original three tiers.

The fourth and uppermost portion, which was made of concrete rather than stones quarried in Porac, was added between 1962 and 1979, Pampanga historian Francis Musni confirmed by comparing photographs.

Two markers hailed the “communal efforts of the people” in rebuilding their church. A broken 1936 iron bell lay on the ground.

But the work was far from over. The parish is “continuing assessment and interventions on the whole church structure,” the Archdiocesan Committee on Church Heritage (ACCH) of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Fernando said in an April 28, 2022, report released at the Inquirer’s request.

The current restoration of this 1726 Augustinian church is the third after the 1863 earthquake and World War II, Musni said.

For the rest, it is the fifth following the Nov. 30, 1645, and July 18, 1880, earthquakes; ruins of the Filipino-American War and World War II; Mt. Pinatubo’s 1991 eruption and succeeding lahar.

Lockdown

A day after the temblor, Archbishop Florentino Lavarias ordered the lockdown of 24 churches to assess safety.

Augustinian priests built 20 of these churches during their missions from 1572 to 1877. Secular priests built the San Luis and Santo Tomas churches. Recoletos supervised the construction of the Mabalacat church while the cathedral in San Fernando rose from the ruins of the 1808 structure burned on the order of Gen. Antonio Luna in 1899, according to a report to the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP).

Based on the results of damage assessments, the ACCH prioritized seven Spanish colonial-era churches and the cathedral. These held on, but the vertical cracks revealed structural problems, according to Fr. Emil Guiao, former ACCH director.

Repairs

The churches were in different stages of deterioration and preservation before the quake, he said, adding that it “intensified” the damage.

The Santo Rosario Church in Angeles City, built from 1877 to 1896, was scheduled for restoration in February 2019. The April quake weakened it more, said Fr. Noli Fernandez.

A May 20 visit by the Inquirer showed that Escuella Taller de Filipinas Foundation Inc. (ET) workers directly employed by the parish stripped the cement on many parts of the inner and outer walls up to the twin towers, allowing the Porac stones to breathe through a lime mixture.

Cracks as big as a fist were filled. The fake columns in the interiors were being reinforced. A fine net held by scaffolds protects devotees from falling objects from the ceilings, now devoid of large electric fans and chandeliers. The main door was realigned.

At the San Agustin Church in Lubao, the oldest Augustinian mission founded 450 years ago, the belfry and previously repaired facade were still supported by scaffolds.

Workers were repairing the belfry’s cupola (dome), parts of which fell. The roof was being replaced while cracks were filled. A steel frame shored the main door.

Soil testing

A May 24 visit to the San Andres Church in Candaba showed workers repairing the belfry, which appeared to be tilting to the right.

The third tier supporting a dome was “most probably added” because it did not use the same kind of stone as those in the first and second tiers, according to Fr. Teodulo Franco.

One of five bells was taken down to reduce its weight on the tower. Like all churches built facing rivers and being the second oldest church in Pampanga, soil testing has to be done to determine ground stability.

Workers were removing the cement plastered on what Franco called “Pinatubo stones” on the exteriors.

The interior walls, which were repainted, were injected with lime. Cracks were closed.

Franco gave up on removing the portico (shaded cover of the main entrance) to be able to show the original facade and the stones. It turned out the portico was made of thick concrete and chiseled to look like adobe.

The retablo (wood niche for images of saints) was being repainted. The floor’s level will be raised to spare it from flooding and a dome atop the main altar will be reconstructed.

At the San Nicolas de Tolentino Church in Macabebe, which is as old as the Candaba church, the floor was filled and raised by as much as 0.91 meters (3 feet) and tiled almost at the level of the windows.

Fr. Marcelino Mandap said the walls were strengthened by removing the cement plaster and replacing it with lime. The same process is due to be done on the exterior of the sacristy. The retablo was given a gilded finish.

In Apalit, the exterior stones of the San Pedro and San Pablo churches appeared to have a shiny gloss to them. First built in 1597 and restored several times until 2017, the paint on the upper inner wall of the main entrance looked to be bubbling and chaffing off on May 24, when the Inquirer visited.

A window near the main entrance was entirely rebuilt to remove a large crack. The images and scenes from the Bible looked neat after the ceiling and walls were repainted.

A crevice below a 1939 marker was filled with a type of stone made to look like adobe. The same technique was used on the arc above the front door. The upper tiers of the twin belfries appear to have been additions in the past.

In Minalin, the scaffolding at the facade of the Santa Monica Church had already been removed. The steel frames bracing two interior arcs at the sides of the main altar were retained. Studies are being prepared, the ACCH said.

In the City of San Fernando, big cracks inside the Metropolitan Cathedral were filled. It also underwent major repainting. Pews were being repaired on May 25. The ACCH said “interventions for the whole structure [are] under study.”

No delays

Monsignor Eugene Reyes, ACCH director, said no significant delays happened to the restoration activities amid the COVID-19 pandemic. “I would not use the word delayed [because] restoration work, to be honest, [accomplishes] slow progress since much care is exercised and planning is necessary.”

The national government has not given funds, although the NHCP marked the Apalit and Macabebe churches, while the National Museum declared the Minalin church a National Cultural Treasure. The Santo Rosario church was the venue of the first anniversary of the first Philippine Republic in 1899, and the Lubao church held important cultural treasures.

The lack of financial support happened despite a 2008 agreement between the Holy See and the Philippine government on the cultural heritage of the Catholic Church and although Republic Act No. 10066 (National Cultural Heritage Act of 2009) exists.

Local governments have not funded either of the two churches. Reyes said churches needed to first be declared by the local government as heritage structures through an ordinance before funding can be released to them.

There has been no local declaration so far. Nonetheless, outside this “official” protocol for local assistance, there are some instances wherein local government assistance is offered in many ways, he said.

The restoration costs vary. The Santo Rosario Parish managed to raise P65 million out of the P100-million goal before the pandemic. Half of the amount has been spent, Fernandez said, adding that fundraising continues to be done.

Transparency

Franco said P21 million was spent on the Candaba church, and all donations were reported through a large tarpaulin displayed on stage. Mandap said about P20 million was used up and around P15 million more needed to be put up.

“The budgeting for these works is to be done on parish-to-parish basis. We at the ACCH do not monitor the costs. We prefer to leave that as an internal logistic of the parish,” said Reyes.

Escuella Taller, which describes itself as a “vocational school that imparts skills and disciplines akin to the field of built heritage conservation,” has been providing expertise or workers.

Reyes said the ACCH makes sure that Escuella Taller, as a technical consultant, is “present in all discussions and meetings with parishes that seek ACCH’s assistance in their attempts or plans for repairs or restorations of their churches or convent structures.”

So far, it is only the Santo Rosario Parish that has fully commissioned Escuella Taller for the conservation and restoration works. Other parishes tapped reputable private contractors.

The ACCH has not created an independent panel to assess the whole restoration process and work because the tasks are multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary by nature. “ET consults experts as it goes along,” Reyes said.

No deadline has been imposed on parishes for the unfinished tasks, said Reyes. “ [The ACCH] guides, assists and supports the efforts [of the parishes], making sure as much as possible that they remain on the right procedures and path of conservation and restoration.”

RELATED STORIES

Pampanga’s heritage churches reopen

NHCP to ask Palace for funds to rehab Pampanga’s quake-damaged churches