Children’s nightmare: Violence, death at the hands of people they trust most

STOCK PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines—Violence, a daily reality for millions of children, kills.

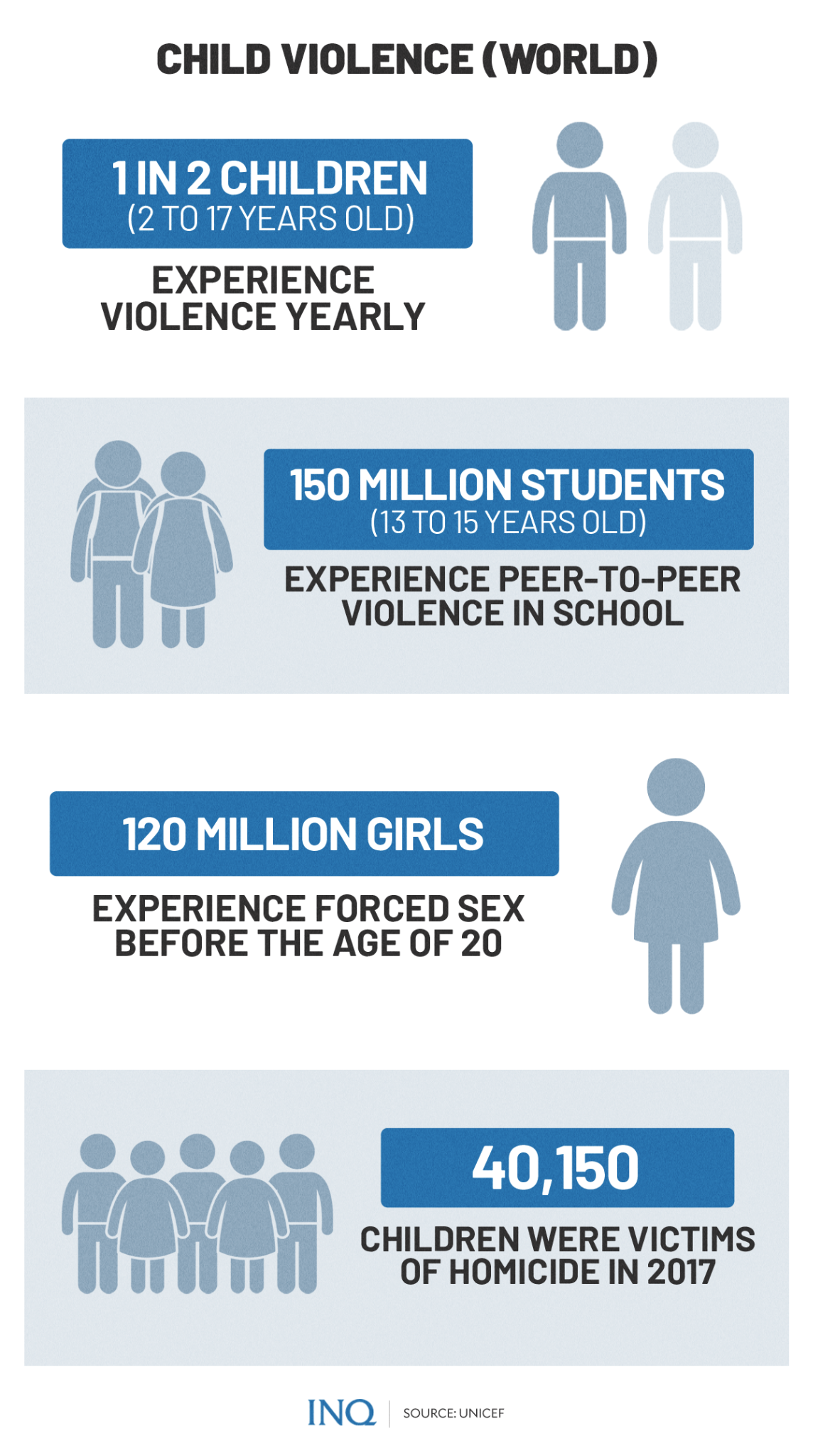

According to World Health Organization (WHO), at least 1 billion children worldwide are exposed to violence—physical, emotional and sexual—every year.

United Nations Childrens’ Fund (Unicef) said last year that violence against children has “long-lasting negative consequences”.

Violence against children continues to be pervasive even with international groups, like WHO and Unicef, trying to raise awareness and prevent it.

In 2017 alone, Unicef said that at least 40,150 children were killed by homicide—around 1.7 children per 100,000.

Homicide rate for boys was 2.4 per 100,000, higher than that for girls—1.1 per 100,000.

Care or violence?

Violence takes many different forms—corporal punishment, attacks on schools, sexual harassment, cyberbullying. All of these have consequences, especially on children.

READ: As COVID shuts down schools, homes become unsafe places for kids

In its #ENDViolence initiative, Unicef stressed that children should feel safe inside their home, school, and even online but “it is in these places that most violence against children happens”.

WHO said that all over the world, 300 million children constantly experience “violent discipline”—violence committed by individuals who are expected to care for them.

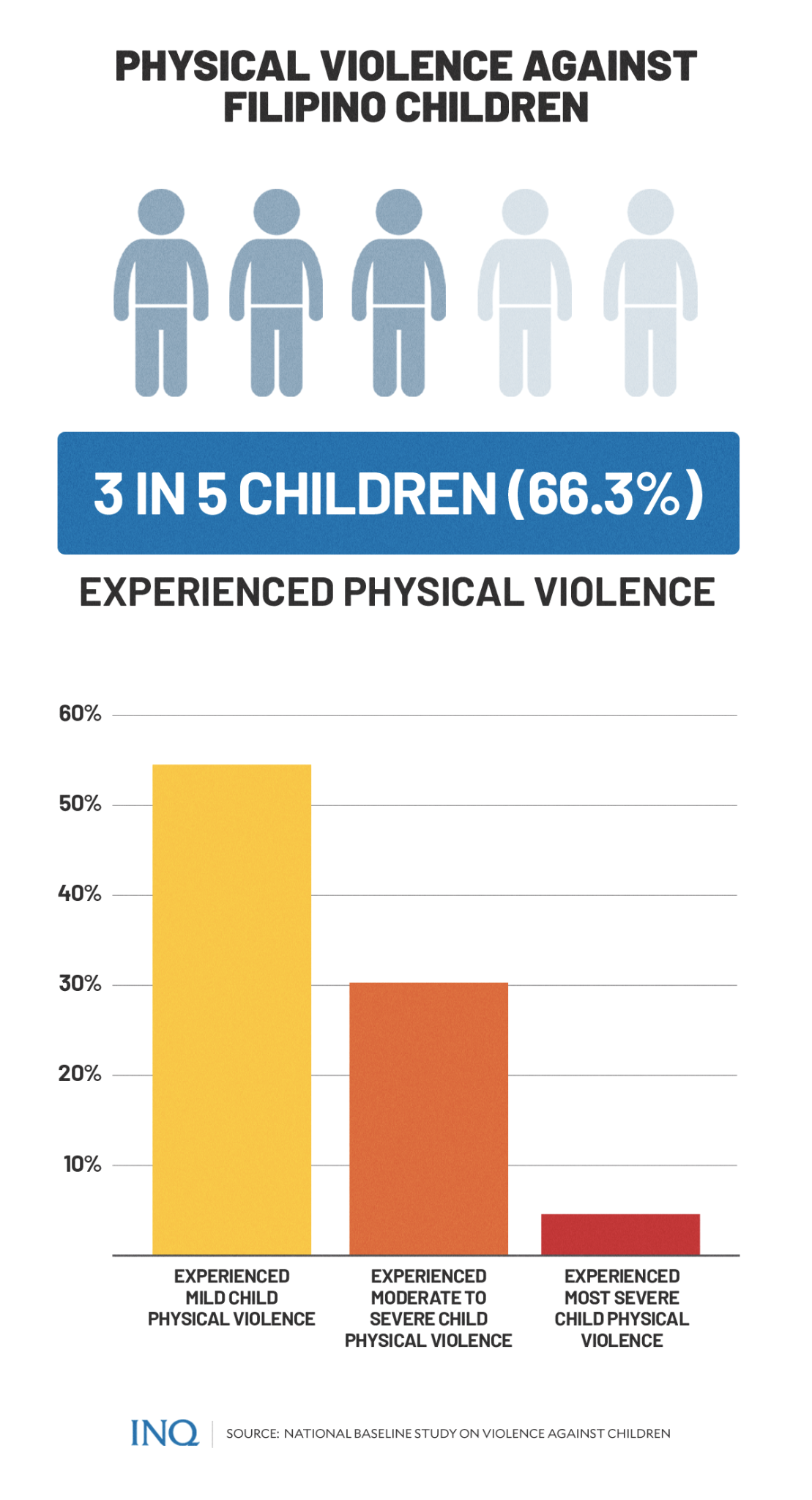

The Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC) and Unicef said the 2015 National Baseline Study on Violence Against Children (NBS VAC) showed that 66.3 percent of 3,866 respondents experienced childhood physical violence.

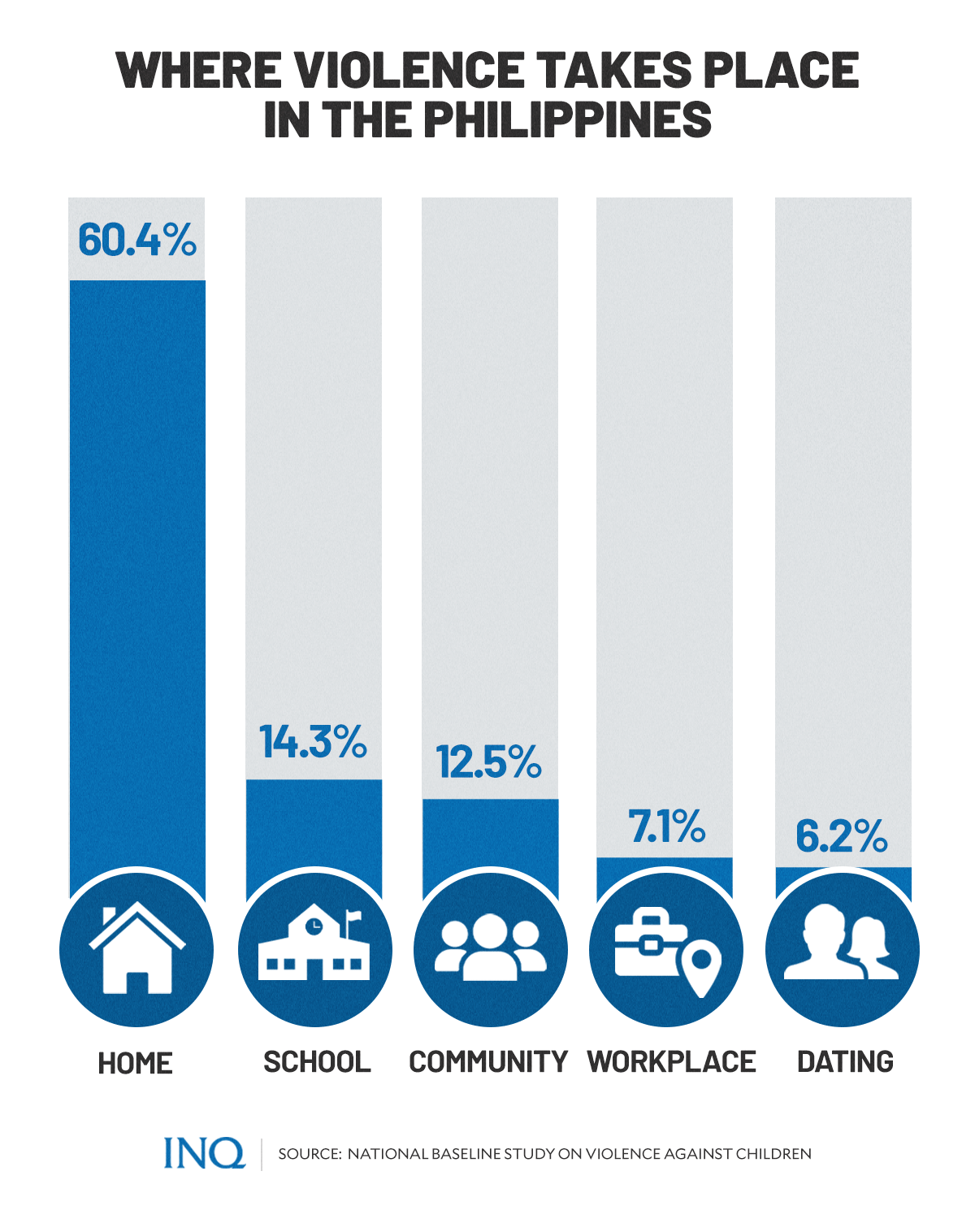

Most of the cases—60.4 percent—happened inside the home; school (14.3 percent); community (12.5 percent); workplace (7.1 percent); and while dating (6.2 percent).

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The NBS VAC showed that mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters were the most indicated perpetrators of physical violence at home. Fathers, however, were deemed responsible for most severe physical violence.

Severe physical violence in the community was mostly committed by neighbors and strangers.

Dark strikes

The Convention on the Rights of the Child said violence could be physical or mental, neglect or negligent treatment, and maltreatment or exploitation.

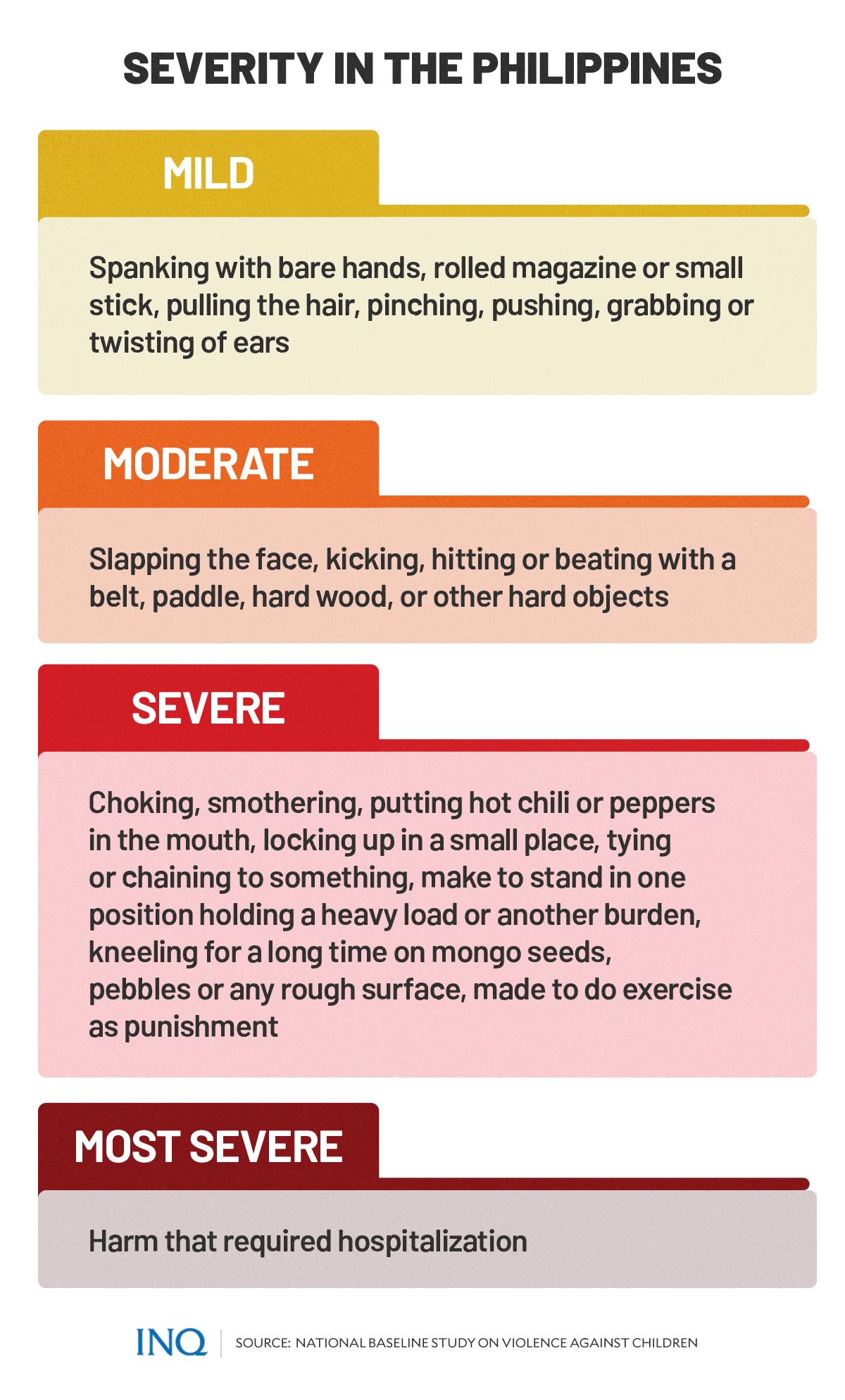

The CWC and Unicef said that in the NBS VAC, the respondents were asked about the severity of violence they experienced. These were the indicators:

- Mild

- Spanking with bare hands, rolled paper or small stick

- Pulling the hair

- Pinching or twisting of ears

- Moderate

- Slapping the face

- Kicking

- Hitting or beating with a belt, paddles, hard wood

- Severe

- Choking

- Smothering

- Putting hot chili or peppers in the mouth

- Locking up in a small place

- Tying or chaining to something

- Make to stand in one position holding a heavy load

- Kneeling for a long time on mongo seeds, pebbles

- Made to do exercise as punishment

- Most severe

- Harm that leads to hospitalization

According to the NBS VAC, 54.5 percent of the respondents experienced mild child physical violence; moderate to severe (30.3 percent); and most severe (4.6 percent).

It said corporal punishment is the most common violence experienced by children—54.55 percent experienced spanking with bare hands, rolled paper or small stick, pulling the hair, pinching and twisting of ears at home.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

More severe punishments, like hitting, kicking, strangling, tying, drowning and burning, were experienced by 30.3 percent of children.

Violence in schools, workplace

“Violence has no place in the lives of children,” Unicef said. But 14.3 percent of those who attended school said they experienced physical violence at school.

NBS VAC showed that 32.5 percent were pinched, 31.5 percent were hit with an eraser or chalk, 25.8 percent said their ears were twisted, and 23.5 percent were spanked with a bare hand, rolled paper, or small stick.

These, the CWC and Unicef said, were committed by a teacher or an adult in the school.

Likewise, 7.1 percent of children who had ever worked experienced child physical violence in the workplace.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Physical violence in the community was experienced by 12.5 of children. Many of the cases—10.6 percent—were serious kinds of child physical violence, like being chained or made to stand with a heavy load.

Unicef also said 150 million students who are 13 to 15 years old experienced peer-to-peer violence in the school, while one in three students who are 13 to 15 years old experienced bullying and engaged in physical fights.

What has PH done?

The United Nations (UN) said corporal punishment in schools is already prohibited in 128 states, but only 10 percent of children all over the world are protected by laws which prohibit violent discipline at home and school.

In 2019 the Philippines was expected to enact a law to protect children from violent discipline, but President Rodrigo Duterte vetoed the Positive and Non-Violent Discipline bill.

READ: Duterte vetoes bill banning corporal punishment for children

The bill, the “Act Promoting Positive and Nonviolent Discipline, Protecting Children from Physical, Humiliating or Degrading Acts as a Form of Punishment,” was returned to Congress without the President’s signature.

While Duterte said every child should be protected from humiliating kinds of punishment and that the bill was a good piece of legislation, he does not share the “overly sweeping condemnation” of corporal punishment.

READ: Unicef urges Duterte gov’t to act on record child abuse cases

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

“I am gravely concerned that the bill goes much further than this as it would proscribe all forms of corporal punishment, humiliating or not, including those done within the confines of the family home,” he said.

“I am of firm conviction that responsible parents can and have administered corporal punishment in a self-restrained manner, such that the children remember it not as an act of hate or abuse, but a loving act of discipline that desires only to uphold their welfare,” he said.

However, contrary to the impression that the law encroaches on parents’ right to discipline their child, Unicef said the proposed law seeks to promote positive discipline instead of corporal punishment—a severe kind of violence against children.

“Positive discipline is a non-violent approach to help and guide children develop positive behavior while respecting their rights to healthy development, protection from violence, and participative learning,” it said.

Not the end

In 2016 the UN launched the INSPIRE, a set of seven evidence-based strategies for states and communities working to eliminate violence against children.

INSPIRE serves as a technical package and handbook for selecting and monitoring effective policies, programs and services to prevent and respond to violence against children.

According to the UN, the letters represent a strategy: I for the implementation and enforcement of laws; N for norms and values; S for safe environments; P for parent and caregiver support; I for income and economic strengthening; R for response and support services; and E for education and life skills.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

The evidence behind INSPIRE approaches shows that 20 percent to 50 percent decreases in prevalence have been achieved by well-designed programs, many of which were implemented in low- and middle-income countries.

The CWC said in 2016 that parents and children they’ve spoken to described an ideal home setting as one where positive discipline is practiced.

For Unicef, the Philippine Plan of Action to End Violence Against Children, which was based on evidence and validated by actual statements from children and parents, highlights the need to provide parents with support through interventions.

“Having a law promoting positive discipline and prohibiting corporal punishment will enable existing programs and policies of the Philippine government to protect more children,” it said.

“The passage of the Positive and Non-Violent Discipline Law institutionalizing positive and non-violent discipline in all settings will strengthen the Philippines’ commitment to Filipino children to take all measures to ensure that their rights are respected, protected and fulfilled,” it said.