Lumad quest for ancestral domain in Bukidnon: Starvation meets gunfire

MANILA, Philippines—It was last April 19 when members of the indigenous peoples group Manobo-Pulangihon in Bukidnon were walking to take back their ancestral land, but shots were fired to drive them away.

Orlan Ravanera said in his Kim’s Dream column that the land, which was converted as a plantation by a company, should be taken back: “Enough is enough […] it is their land.”

The Federation of Free Farmers (FFF), which condemned the violence, asked Malacañang and local officials in Bukidnon “to act decisively to prevent violence and to enforce the ancestral land rights of lumad (indigenous peoples)”.

Endless misery

It was in 2017 when 1,000 indigenous families were driven away from a 1,000-hectare land in Barangays Butong and San Jose in Quezon, Bukidnon.

READ: Bukidnon tribe won’t live as ‘squatters,’ seeks return to ancestral land

The National Commission for Culture and the Arts said there are 749,042 Manobos in the Philippines, especially in Sarangani, Agusan del Sur, the Davao provinces, Bukidnon, North Cotabato and South Cotabato.

Article continues after this advertisementSince then, the Manobo-Pulangihon tribe lived through extreme heat of the sun and when there’s heavy rainfall, the lumad tremble in a cold night, sleepless with empty stomachs.

Article continues after this advertisementThis, as they lived inside broken tents in the backstreets of Quezon, Bukidnon. “They could not bear it any longer […] living in hunger and extreme poverty, eating only kamote once a day or nothing at all and drinking in a nearby river,” Ravanera said.

Last year, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) told the Manobo-Pulangihon tribe that its Certificate of Ancestral Domain will be released before yearend since the Forest Land Grazing Management Agreement given to a company has already expired.

Within reach?

Cagayan de Oro Archbishop Emeritus Antonio Ledesma, S.J., last year, initiated a series of conversations with lawyers and even representatives from the government to have the legitimacy of the tribal ownership of the ancestral land certified.

Finally, on Oct. 6, 2021, NCIP chairman Allen Capuyan signed a certificate while six NCIP commissioners likewise certified that the 1,111-hectare land is the ancestral land of the Manobo-Pulangihon tribe, Ravanera said.

The NCIP said last year that there was a delay in the resolution since there were four tribes that were laying claim over the land.

READ: Multiple claims delay award of ancestral domain in Bukidnon

FFF chairman and former Agriculture Secretary Leonardo Montemayor said the disputed land had been originally leased to the Montalvan Ranch in the 1960s.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Somehow, he said, a company managed to have leasehold rights over the land. In 2018, the 25-year lease period ended and the land was reclassified by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources as forest land.

Montemayor stressed that DENR officials from President Fidel Ramos’ administration declared that the area was part of the ancestral land of the Manobo-Pulangihon tribe, as indicated by the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997.

Taking back what is theirs

The FFF said that on April 18, Datu Rolando Anglao met with Quezon Mayor Pablo Lorenzo III, Capuyan, and some government officials to let them know that the lumad will take back a 4-hectare land that is not being used as a plantation.

The lumad said there is nothing to worry about since nothing will be destroyed. Even Capuyan said it is a “win-win situation”. Since there was no opposition, the chieftains asked for the presence of NCIP, Commission on Human Rights, the police and the military.

This, they said, is a preemptive move against violence that might take place.

Ravanera said that on April 19, the military and the police arrived at 11 a.m. While they were invited to eat with the lumad, he said they decided to stay near the gate.

When the ritual was finished at 2 p.m., the indigenous peoples walked toward the 4-hectare land while carrying a white flag, saying “We’re starving. We will till the vacant land and build houses there. Our children are already living in misery”.

GRAPHIC: Ed Lustan

Ravanera was with presidential candidate Ka Leody de Guzman and senatorial candidates Roy Cabonegro and David D’angelo then. He said they also called for “peace and development” for the indigenous peoples.

READ: Leody suing shooters; PNP faults lack of ‘coordination’

However, a shot was fired and it hit one individual. While they thought that it was only a warning, a series of shots were fired and it lasted for 15 minutes. They were told to “go out, go out”. Five were hurt.

READ: Leody de Guzman nearly hit, 5 hurt as gunfire greets sortie

“We were like rats being driven away through indiscriminate firings. The military and the PNP (Philippine National Police) did nothing to intervene,” Ravanera said.

He said that when the shots were fired, indigenous peoples, even women and children, ran away to escape death, but the military and police “were only there, doing nothing”.

Fight not easy

The fight for the rights of indigenous peoples, especially for their ancestral lands, is never easy. The incident in Bukidnon, where five individuals were hurt, is only one of the countless attacks against them.

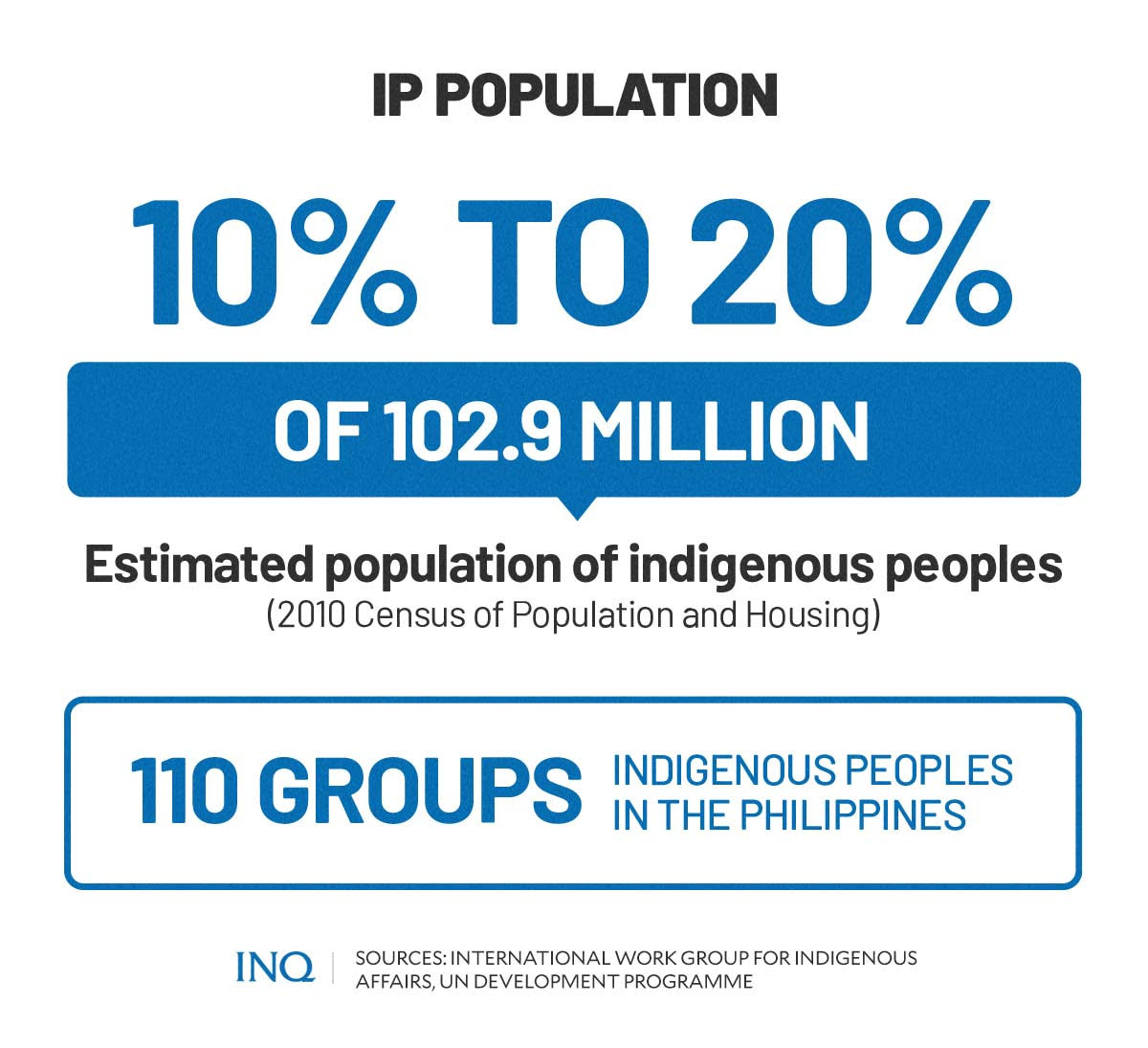

The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) said 10 percent to 20 percent of the 102.9 million Filipinos are indigenous peoples, as indicated in the 2010 Census of Population and Housing. The United Nations Development Programme said there are 110 indigenous peoples’ groups in the Philippines.

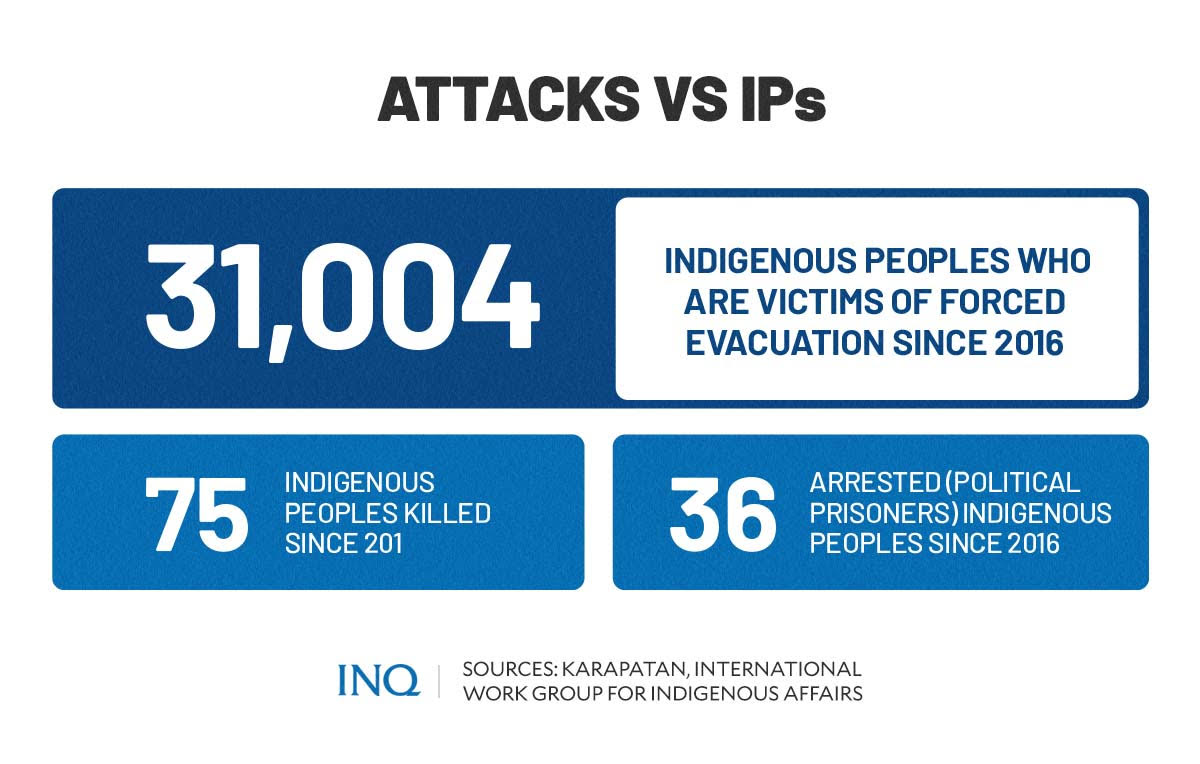

Data from the human rights group Karapatan and IWGIA showed that since 2016, 75 indigenous peoples had been killed, 36 were arrested and 31,004 were victims of forced evacuation.

The Asian NGO Coalition (ANGOC) said land and natural resources have always been sources of conflict: “Violence due to land and natural resources is ever prevalent with resultant deaths and damages, sustained by those with less power, particularly the rural poor. Not only is the number of land and natural resource conflicts rising, but also the degree of conflict–employing violence in many cases–is intensifying.”

“Rural poor communities experience forced evictions from their homes, displacement and damages to livelihoods and property, severe hunger and poverty, and exposure to geophysical and health hazards and risks in the environment especially complicated by natural disasters and climate change,” it said.

In a 2018 ANGOC research on land conflicts, 352 cases have been documented, covering 1,317,024 hectares, or four percent of the total territory of the Philippines. Such conflicts lasted an average of 14 years with some cases lasting less than a year to as long as 68 years:

- Mindanao: 208 cases

- Luzon: 82

- Visayas: 62