Summers in Laguna Lake: The continuing drive to preserve water quality

Image: Daniella Marie Agacer

MANILA, Philippines—Every summer, tourists and residents near the Laguna de Bay could get a glimpse of not only the lake itself but also the cleanup drives in several portions of the body of water.

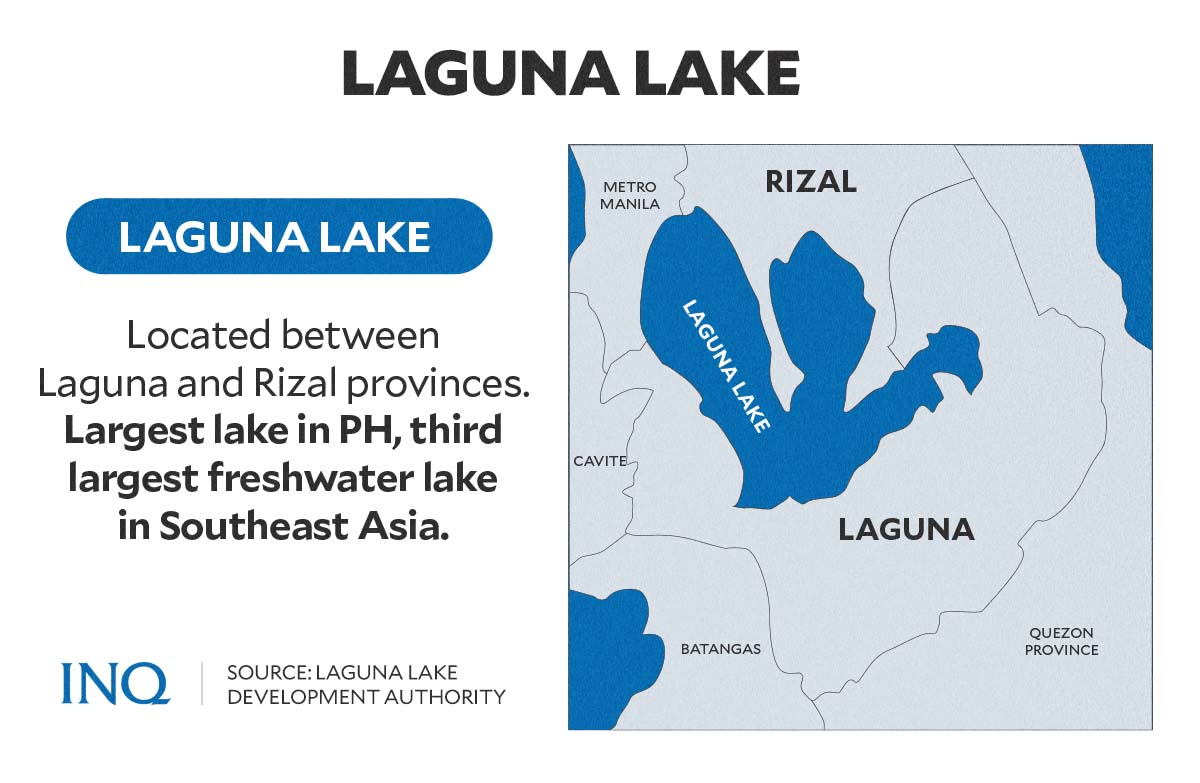

The Laguna Lake, which is located between the provinces of Laguna to the south and Rizal to the north, is known as the largest lake in the country and the third-largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia in terms of surface area—with 911 to 949 km² or 352,000 to 366,000 square meters of surface area.

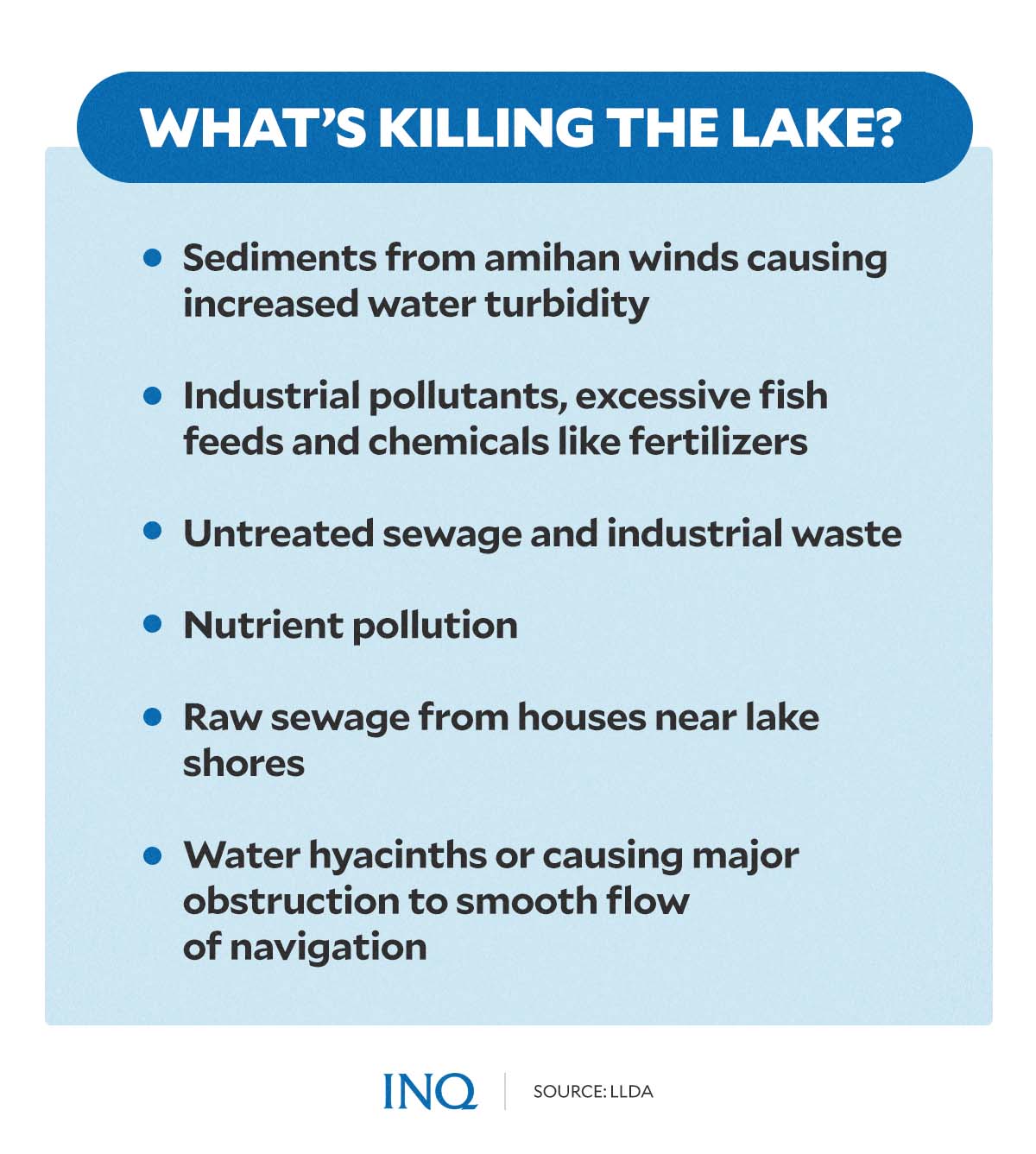

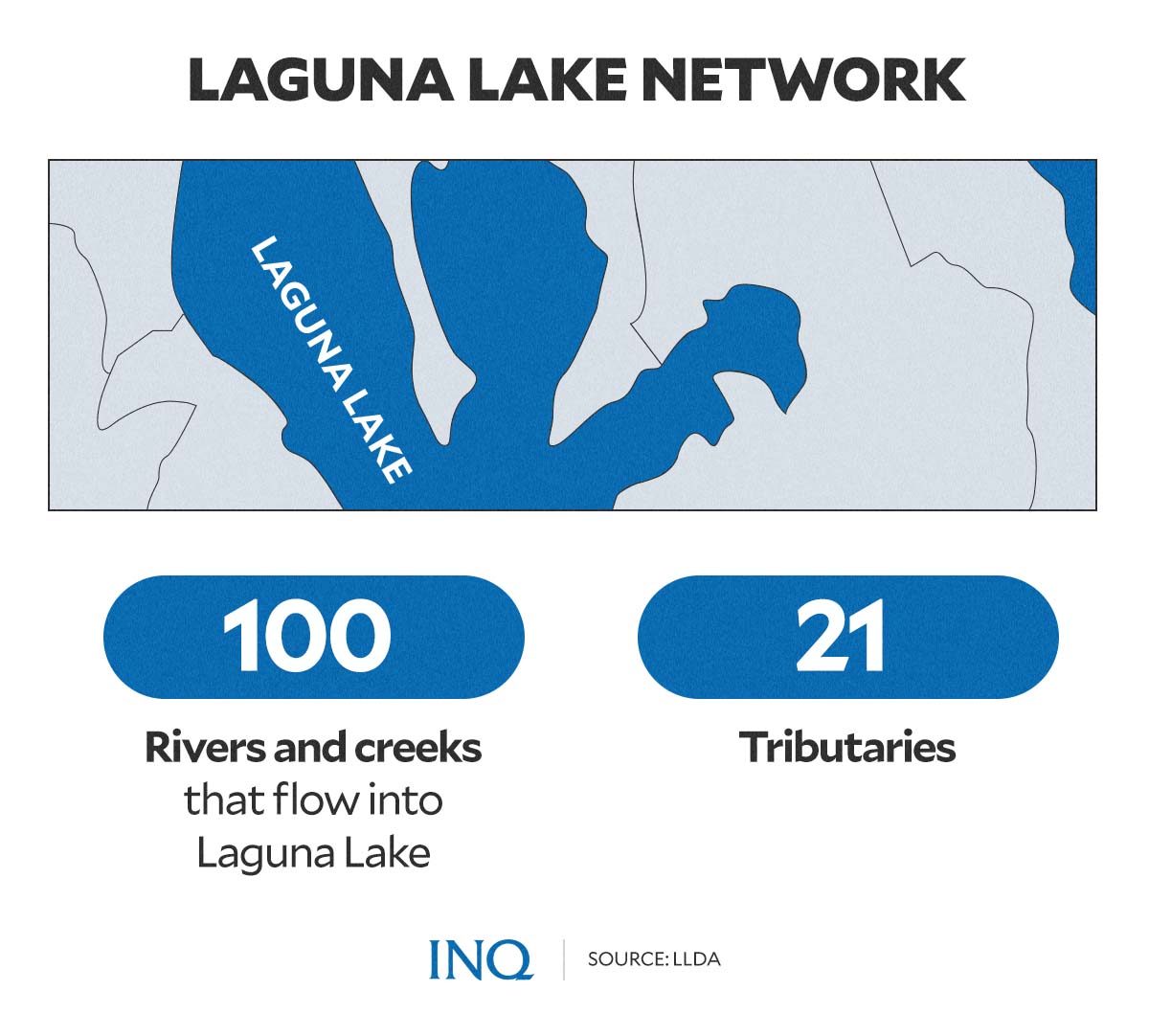

According to the Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA), at least 100 rivers and streams drain into the lake, of which 21 are identified as tributaries.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

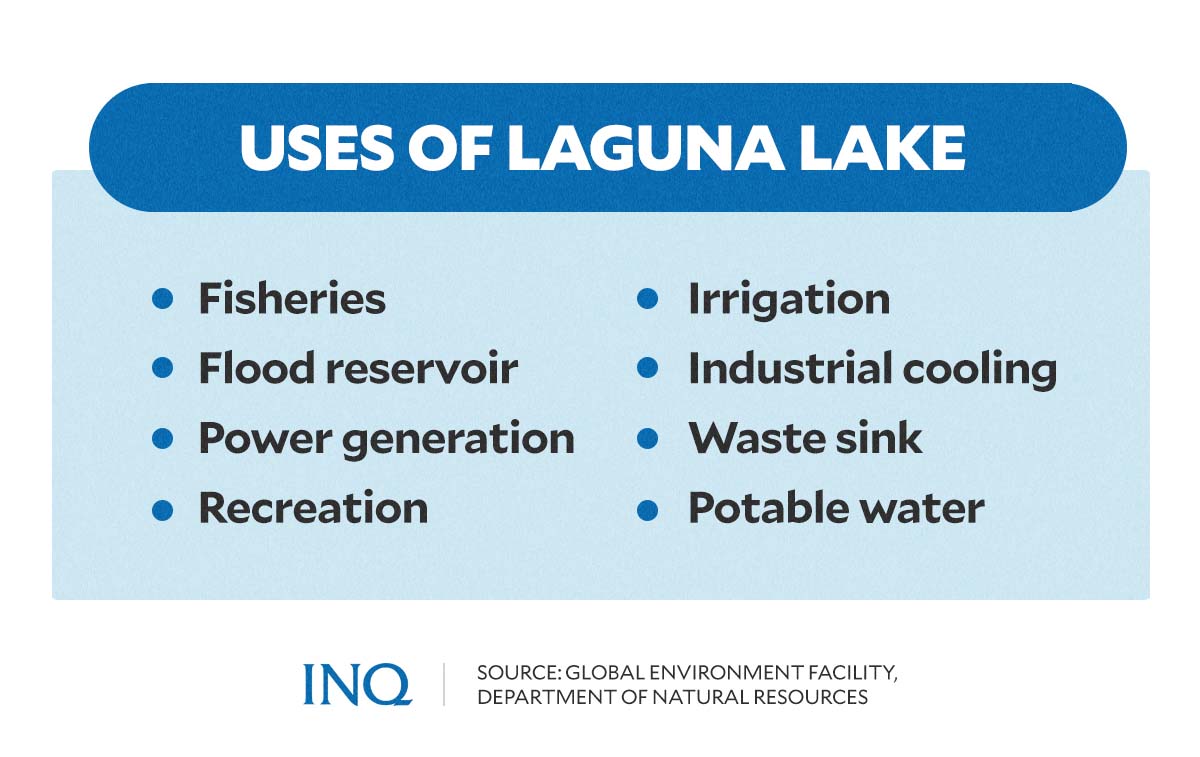

Currently, the lake is being used for fisheries, flood reservoir, power generation, non-contact recreation, irrigation, industrial cooling, waste sink for solid and liquid wastes for different sources, and domestic water supply.

With its many uses, it is important to maintain the cleanliness—specifically, the quality of water—of the lake. Several wastewater pollution sources could hinder operations that needed water supply from the lake due to water contamination and other issues.

In this article, INQUIRER.net will detail more about maintaining the country’s largest lake, as well as plans and ongoing campaigns which could help improve the quality of water in the lake.

Summer cleanups

While there are cleanup drives regularly done in the lake throughout the year, one of the peak cleanup activities of LLDA usually takes place every summer—around April to May—when more water hyacinths or water lilies propagate in the lake.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

Emiterio Hernandez, manager of the LLDA Environmental Regulatory Department, told INQUIRER.net in an interview that the LLDA works with other agencies such as the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) when clearing out water hyacinths, mostly in portions of the lake near Rizal province.

“We usually do that during summer months because it is easier to transport and gather [the water lillies]. It is also easier to operate the equipment compared when during rainy seasons since the waves and winds are stronger,” Hernandez explained, speaking in Filipino.

“If we don’t clean it all up during the summer months, the water lilies will be pulled by strong waves and winds and pushed to other parts of the lake or to ports—which could cause issues in operations of small fishing vessels or boats,” he said, adding that the cleanup drive to remove water hyacinths during summer is mainly to avoid issues in navigation.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

Hernandez also explained that water lilies, when left to decompose in the lake, will degrade the quality of water in Laguna Lake.

Water lilies could also cover an entire portion of the lake, which could lead to lesser light penetration in the covered water. When this happens, there would be lesser fish in the area—which can affect the livelihood of fishermen.

“[The removal of water hyacinth is not only during summer, all throughout the year, whenever we see that there is a fast propagation of water lily in the lake, but we will also immediately coordinate with the MMDA and DPWH to deploy equipment,” said Hernandez.

“Unfortunately, LLDA does not have its own equipment yet but through the efforts and assistance of other agencies, we can help the local government units (LGUs) surrounding the lake to reduce the water lilies,” he added.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

Aside from water lilies, the LLDA likewise focuses on cleaning or removing filamentous freshwater green algae in the lake, which bloom more during the summer season.

While the algae—also known as pond scum of the genus Spirogyra—does not produce toxins that can make humans and animals sick, it can deplete the oxygen levels in the lake once these algae decompose.

In June 2019, residents in Muntinlupa who were near the Laguna Lake complained about foul odor coming from the lake—described as “similar to the stench of pig pens and decaying fish”—which was due to algal bloom.

READ: Algae in Laguna de Bay not harmful despite smell

Hernandez said the LLDA is planning to procure a number of solar-powered paddle wheels to help increase the water oxygen levels in the lake.

These actions, however, are just some of the short-term measures being implemented by the agency “to somehow address the water quality problems in Laguna Lake.”

“Definitely, we need to have long-term rehabilitation measures in Laguna Lake,” said Hernandez.

Managing sediments

Other than water lilies and algae, another issue that threatens the quality level of the water in Laguna Lake are sediments deposited in the lake, mostly during the rainy season.

“Laguna Lake has long been the depository of sediments coming from the watershed. We can observe the sedimentation during the rainy season. During the rainy season, the water in the lake is not just rainwater but murky water—there are suspended sentiments,” said Hernandez.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

“For the longest time, we cannot remove the sediment deposit. It has already affected the depth of the lake from more than three meters to on average 2 and a half meters because of sedimentation,” he added.

Hernandez said one way to manage sediments in the lake could be through dredging projects.

“Maybe we need dredging, of course with due consideration to the environmental impact while doing the dredging, but maybe we need that to restore the depth of the lake,” he said.

“We could also address the high sediment deposit through planting trees.”

Dredging operations in the lake, said Hernandez, could increase the water storage capacity of the lake. It could also clear out any blockage in the river mouths, which could help recede flood faster.

“Of course, we cannot prevent floods just by dredging but [it will be beneficial in terms of addressing] the duration of flooding,” he said.

However, dredging activities in the lake could also have negative impacts on fisheries. Some fishermen in the area, where the dredging operations are conducted, will not be able to fish due to sediments in the water.

Still, Hernandez explained that dredging operations—if it will be used as a solution—should have a detailed plan, which includes programs that can assist affected fishermen and public and private fisheries.

So far, the LLDA has no dredging projects lined up in the pipeline.

On water quality

Based on criteria in the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Administrative Order No. 34 Series of 1990, the Laguna Lake was classified as Class C.

Among the beneficial use of Class C lake fresh surface water include:

- Fishery water for the propagation and growth of fish and other aquatic resources;

- Recreational water class 2 (such as boating);

- Industrial water supply class 1 (from manufacturing processes after treatment).

For Laguna Lake, fortunately, it was able to meet the threshold for Class C waters.

“Unfortunately, most of the tributaries of Laguna Lake were declared worse than Class C. Some were even worse than class D—including those that are located near Metro Manila. These tributaries are only fit for irrigation,” Hernandez explained.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

Fresh surface water that is declared worse than Class C or Class D is no longer able to propagate fish.

In addition, Pasig River—connected to the Laguna Lake’s only outlet, the Napindan Channel—was declared Class C. However, water from the river causes fish kills.

READ: Pasig River makes international waves despite being dead

READ: PH rivers yield bulk of Asia’s marine plastic wastes

During the dry season, water elevation in Laguna Lake drops and allows the backflow of water from Manila Bay to the lake. While this could be beneficial to fish species in the lake, the initial flow of saltwater could be harmful.

Graphic: Ed Lustan

Water from the Pasig River drains out to Manila Bay. This means that the initial backflow from Manila Bay to the lake would be the polluted saline waters from the Pasig River—which then causes fish kills.

“During the first backflow of water in the dry season, we always expect that there will be fish kill especially in areas in Taguig, Muntinlupa, and Binangonan—all of which are near Pasig-Napindan River,” Hernandez said.

Eyes on tributaries

Tributaries classfied as Class C and Class D, according to Hernandez, could further increase the volume of wastewater in Laguna Lake.

“The LLDA has river rehabilitation programs to address these kinds of water pollution,” said Hernandez.

“Unfortunately, under the Clean Water Act, we can only monitor the point sources of pollution such as commercial and industrial establishments as well as the households—which is the major contributor of wastewater pollution in Laguna Lake,” he added.

LLDA, according to him, can only advise water districts and water service providers to regularly unclog septic tanks. This is crucial because when clogged septic tanks overflow, untreated sewage could go to the lake’s drainage.

“Unfortunately, at least less than 20 percent of houses in Metro Manila are connected to sewerage system so we still have a lot to go before we can say that we have finally improved the lake’s water quality.”

Increase in cost

Since the lake has also been used as a source of raw water for domestic water supply, an increase in the water’s turbidity—as well as degraded water quality—would mean that water service providers would shell out more money for additional treatment costs.

In turn, this could impact the prices of water supply in some concession areas. It could also reduce the production of raw water.

“That is why it is important to ensure to maintain Laguna Lake at a certain level of water classification,” said Hernandez.

In 2010, Maynilad Water Services, Inc. (Maynilad) tapped the lake as raw water source. It has two completed treatment facilities in Muntinlupa, producing a combined output of 300 million liters per day and serving around 1.2 million customers in the southern part of its concession.

Last year, it started the construction of another treatment plan which was designed to produce 150 million liters per day (MLD) of potable water. This will primarily serve Cavite areas and other areas south of the West Zone concession.

Manila Water Company Inc. meanwhile has a treatment plant in Rizal, which is capable of distributing 100 MLD of potable water.

Ongoing Hungarian deal benefits

“Definitely, we need to have long-term rehabilitation measures in Laguna Lake,” said Hernandez.

Currently, the LLDA has ongoing studies and collaboration with the Hungarian government. The engagement with the foreign country aims to put up wastewater facilities in hotspot areas of Laguna Lake’s tributaries.

“It includes an early warning system which can help detect areas with high algae or low oxygen levels, among others, so the LLDA can be warned about these kinds of water quality issues,” Hernandez said.

The deal is being considered as one of the long-term solutions to preserve and improve water quality levels in Laguna Lake.

In December 2020, a memorandum of cooperation was signed by the LLDA and the private firm, Hungarian Water Technology Corp., during the second Philippines-Hungarian Joint Commission for Economic Cooperation. The project could possibly be funded by the state-owned Hungarian Eximbank.

Aside from installing 47 water quality monitoring stations, another component of the deal is a comprehensive feasibility study for the rehabilitation of the heavily silted water body.