Pasig River makes international waves despite being dead

The Binondo-Intramuros Bridge may be completed by September 2021 as it is now 50 percent complete the DPWH said in a statement. The bridge will link the old walled city and Manila’s business district which is separated by the Pasig River.-INQUIRER/GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

MANILA, Philippines—The Philippines earned an unflattering distinction recently for having the most polluting body of water and leading source of plastic wastes in the ocean—Pasig River.

The main waterway that snakes itself through Metro Manila, the Philippines’ industrial and commercial nerve center, had been found to be more pollutive than several other notorious rivers in the world, notably the Ganges River in India where millions bathe yearly for one of the world’s biggest religious festivals, Khumb Mela.

That Pasig River’s condition has drawn international attention is not a surprise and is presented in a study of rivers worldwide published last April in the Science Advances, a peer-reviewed journal by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) had provided details.

The study delved into where most of the plastics now floating and swimming in the oceans originate and found that among 20 countries that had been tagged as major contributors of plastic wastes, the Philippines was numero uno.

More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean

Of 1,656 rivers in the Philippines that were found to contribute plastic wastes to the oceans, Pasig River topped the list.

The river, which directly connects to the country’s main port for maritime trade and travel, and two key freshwater lakes in the Philippines—Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay—stretch for 27 kilometers with an average width of 91 meters and an average depth of 1.3 meters.

It was classified by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) as a Class C river in terms of usefulness. A Class C river can be useful for growing fish and other marine resources. Yes, grow fish.

A Class C river is also ideal for boating and other recreational activities. Yes, recreation.

It also, however, may be tapped to supply industrial water for manufacturing. Here, Pasig River is doing more than it can.

No fish growth, no recreational activities plus a lot of industries would, in 1990, lead to a declaration by ecologists of Pasig River as biologically dead and incapable of sustaining marine life.

How did Pasig River, object of folklore and stories about swimming in its nearly crystal clear water, end up dead?

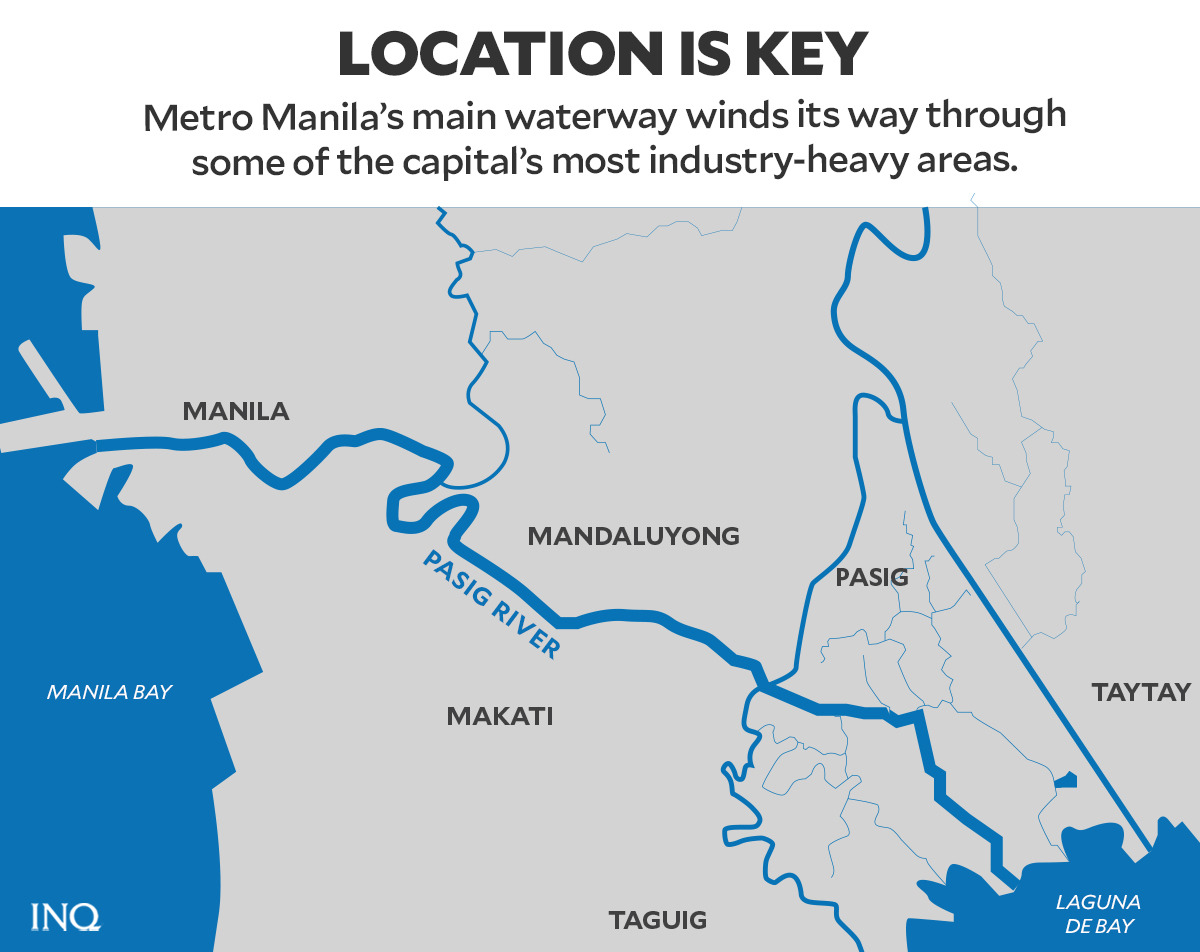

Location is key

Pasig River is right smack in the middle of Metro Manila’s heaviest industries in the cities of Taguig, Pasig, Makati, Mandaluyong and Manila plus the municipality of Taytay.

Its location made it ideal as a path for major means of transport, water sources for domestic and industrial sources, a place for recreation and habitat for aquatic life. It was able to support transport and as water supply for domestic and industrial needs. Forget about it being a habitat for aquatic life or as a place of recreation.

Pasig River’s major tributaries include:

- San Juan River (6.2 kilometers)

- Taguig-Pateros River (11.5 kilometers)

- Marikina River (19.3 kilometers)

- Napindan River (8.4 kilometers)

Additionally, it has 43 minor tributaries, mostly located in Manila.

While Pasig River’s location was considered by many as “strategic,” population growth, infrastructure development, and increased economic activities in surrounding cities led to its deterioration.

Plastic emission

According to a separate 2010 study by experts Joan Gorme, Marla Maniquiz, Pum Song, and Lee-Hyung Kim, domestic waste accounts for 60 percent of the total pollution in Pasig River.

At least 33 percent were from industrial wastes from manufacturing facilities like tanneries, textile mills, food processing plants, distilleries, and chemical and metal plants.

At least seven percent is highly visible—solid wastes dumped straight into the river.

According to the Water Pollution Control handbook by the United Nations (UN) Environment Programme and World Health Organization (WHO), the river has become “a dumping ground of informal settlers living along the banks of the river and its tributaries as well as surrounding establishments.”

“Due to the continuous dumping of wastes, the river bed has become more and more silted with organic matter and non-biodegradable garbage,” said Gorme et al.

The DENR-NSWMC (National Solid Waste Management Commission) in 2012 revealed that solid waste generation in Metro Manila is around 8,200 tons per day.

In 2019, around 7.17 percent of mismanaged plastic waste, or plastic that is wantonly thrown away, went to the ocean.

The study published in AAAS also showed that Pasig River, as the top polluter of the world’s oceans, dumps an estimated 38,000 tons of plastics into the oceans every year.

It is at least 6.43 percent of the global ocean plastic pollution.

“It is important to mention that the Pasig River is a very poor and degraded water body that is unable to cope and balance with the rapid urban growth,” said the report by Gorme et al.

“The water is stagnant, black, and stinking, and the bed seems to be devoid of any slope,” the report said.

“The drainage system in the river tributaries has been choked due to high siltation and dumping of garbage including non-biodegradable wastes,” the report added, noting that slums along the river banks and wastes from dwellers are worsening the river’s already worst condition.

What is in the waters?

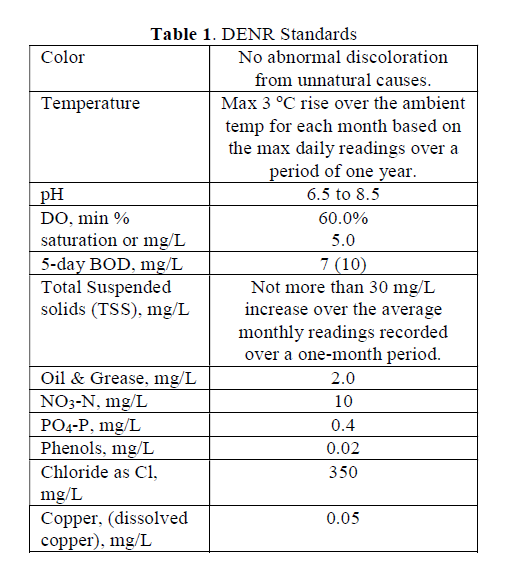

Water quality of Class C rivers is measured following the set criteria under the DENR Administrative Order No. 34 issued in 1990.

The criteria detail the acceptable color, temperature, pH level, solid waste, and other parameters for Pasig River.

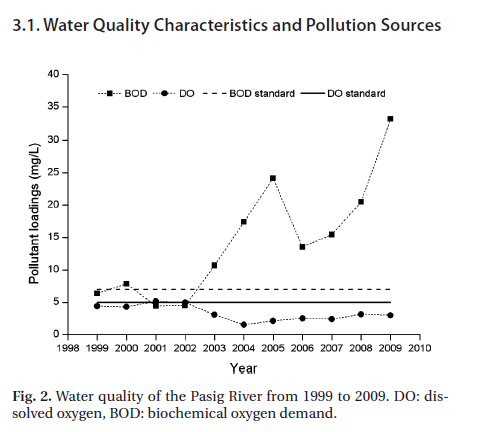

But the 2010 analysis by Gorme et al. showed that from 1999 to 2009, the water quality of Pasig River was toxic and failed to meet the standard clean level of 5 and 7 milligrams per liter (mgL) dissolved oxygen and biochemical oxygen demand, or BOD.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) content is a very useful parameter to show the ecological health of any body of water.

SCREEN SHOT FROM THE WATER QUALITY OF PASIG RIVER IN THE CITY OF MANILA, PHILIPPINES: CURRENT STATUS, MANAGEMENT AND FUTURE RECOVERY BY GORME ET. AL.

At least 295 tons of BOD has been discharged by Pasig River every day in 1990, the researchers found. At least 44 percent of it was domestic, 45 percent household and 11 percent was solid waste.

In 2000, the total BOD load went down to 240 metric tons per day, “but the [decreasing] trend continued to deteriorate over the subsequent years.”

High levels of dissolved oxygen, or DO, had been attributed to domestic and industrial waste around the river with about 58 percent (192,999 tons) generated by domestic waste and 43 percent (138,000) tons from industries.

Measuring the DO as a basis for calculating the oxygen deficit of the water and BOD to determine the oxygen loss rates is a simple model to determine the river’s water quality.

The amount of total suspended solids, or TSS, in Pasig River in the first quarter of 2009 was also high. Most solid particles found in water samples from the river were silt, decaying plants, animal matter and domestic and industrial wastes.

According to the study, volume of phosphate, oil and grease was also very high.

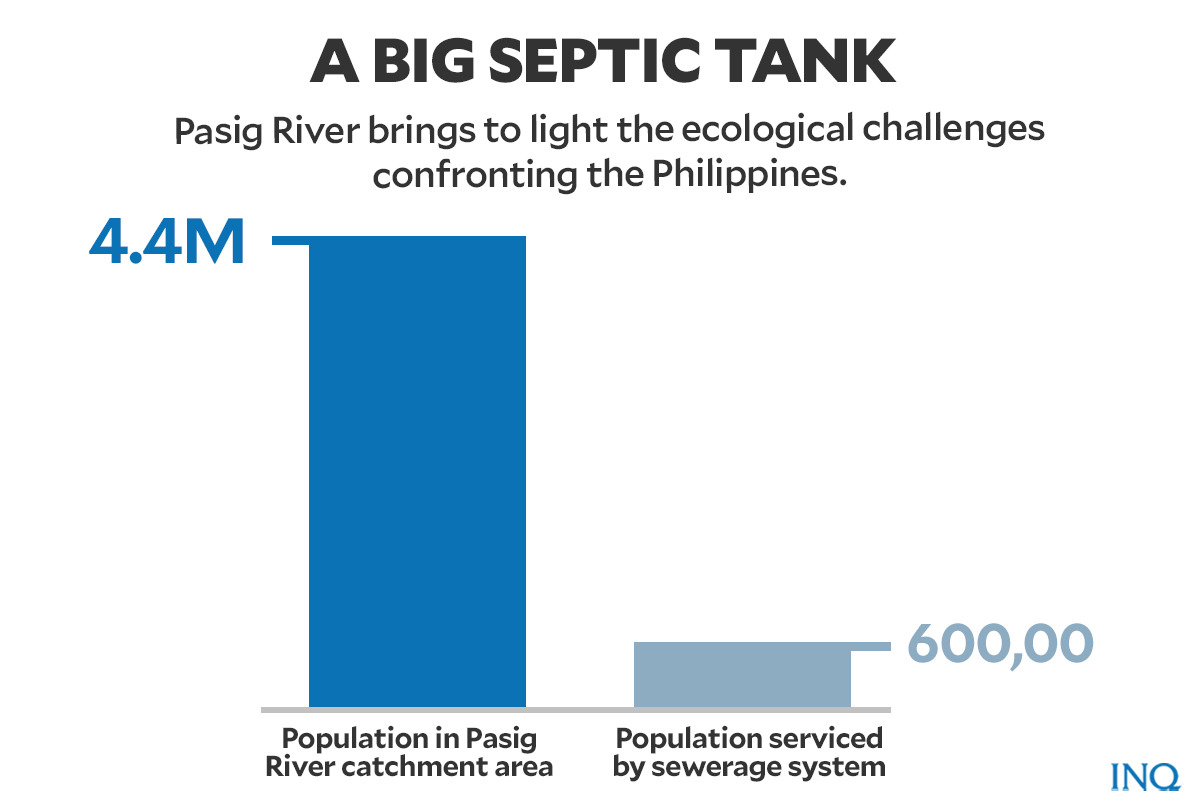

The researchers said at least 4.4 million people lived in the Pasig River catchment area but only 600,000, or 12 percent, are “serviced by the sewerage system that treats domestic waste water before their discharge.”

“Untreated waste waters from the remaining 88 percent of the population flow through canals into viaducts leading into the river,” they added.

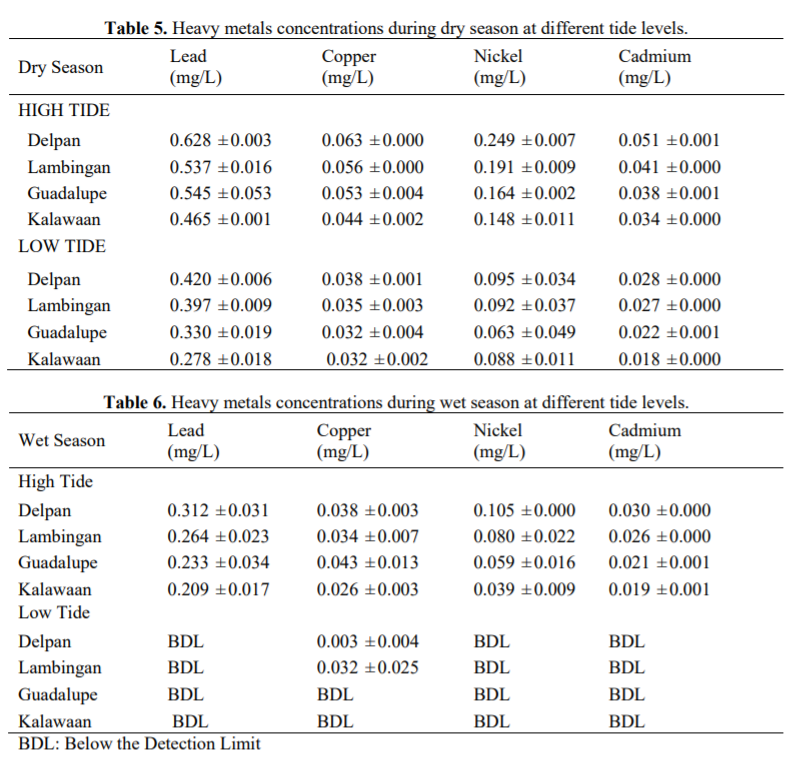

A separate study by Parnoda et al. in 2019 explained that varying seasons and astronomical tides affect river flow pattern and heavy metals concentrations in Pasig River.

The paper found that a low flow rate during the dry season can cause heavy metals, like lead, copper, nickel, and cadmium, to settle in the sludge of rivers.

This could result in the clouding of the water and coating of the riverbed.

“Inorganic wastes can smother the riverbed in a blanket of toxic residue and cloud the water,” the study said.

“This clouding blocks the penetration of sunlight into the water and therefore obstructs photosynthesis and inhibits plant growth, similar to what can be observed during eutrophication,” it added. Eutrophication is excessive amounts of nutrients in a body of water.

The wet season causes a distinct flow pattern in four different sampling sites – Delpan, Lambingan, Guadalupe, and Kalawaan sampling stations.

During a high flow rate, contaminants in the river will be washed out to Manila Bay.

It should also be noted that results from the study showed that in both seasons and flow patterns, the level of copper was above the standard number set by DENR.

Government intervention

In past years, the government has made an effort to rehabilitate the river by clearing piles of plastic wastes. It started in 1973 through the Pasig River Development Council (PRDC) and the implementation of the Pasig River Development Program (PRDP).

“These were mainly concerned with the relocation of informal families and dredging of the silted portions of the river, relocation of two large sewers in Manila Bay and the construction of concrete railings along its banks,” Gorme et al. explained.

Unfortunately, both PRDC and PRDP were abolished in 1987 due to lack of support.

The government again tried to revive the Pasig River in 1999 through the creation of the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission (PRRC). Its main goal was to supervise, monitor plans, programs, projects and activities, and enforce rules and regulations for the rehabilitation of the river.

Among activities implemented by the PRRC to improve the river’s water quality were:

- Mandatory localized sewage treatment.

- Sanitation projects for secondary sewage households.

- Expansion of community-based solid waste management.

The commission had a successful run in 2018 and was given the first Asia River Prize Award by the International River Foundation.

But in September 2020, President Rodrigo Duterte declared Pasig River to be “uncleanable.” A couple of months later, he ordered the abolition of PRRC, calling it a waste of time and money.

The commission’s powers and functions, listed by Executive Order No. 93, was then transferred to other government agencies and offices like Manila Bay Task Force, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development (DHSUD) and the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA).

According to Gorme et al., failure to achieve the target water quality for Class C rivers, like Pasig River, was due to insufficient government funding aside from lack of support from Metro Manila residents and natural disasters.

“The lack of monetary resources had resulted in the weak implementation of government projects,” the study said.

“The government has not been able to provide enough wastewater facilities to treat huge discharges coming from domestic, industrial and solid wastes, with the majority of these wastes being discharged directly into the river without proper treatment,” it added.

Limited scope

Rankings of rivers in the study published in the Science Advances, however, focused only on the volume of plastics each river spits into the oceans.

For instance, the Ganges River or river Ganga in India was ranked only eighth on the list and had a 0.63 percent share of ocean plastics.

However, in 2019, India’s Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) found that the river’s fecal coliform bacteria, like E coli, is three to 12 times higher than the permissible limit.

The CPCB said that fecal coliform in the Ganges was at the highest level at 30,000 most probable number (MPL) per milliliter (ml).

This is 12 times the permissible limit—2,500—and 60 times more than the desirable limit—500.

According to the CPCB, these dangerous levels of fecal coliform —usually from excreta transferred through untreated sewage—increases the risk of contaminating diseases.

What now?

To address plastic waste management in the Philippines, World Bank recommended the following:

- Raise sorting efficiency

- Set recycled content goals for all major end-use applications

- Require “design for recycling” standards for plastics

- Enjoin more chemical and mechanical recycling capacities

- Create industry-specific requirements to collect post-use plastics

- Restrict plastics disposal.

Last February, the National Solid Waste Management Commission (NSWMC) approved a draft resolution to list plastic straws and coffee stirrers as non-environmentally approved products, or NEAP.

The DENR has vowed to eliminate the use of plastic straws and plastic coffee stirrers in the country, saying “this is long overdue and we need to catch up with the demand of solid waste management in our country.”

RELATED STORY: PH rivers yield bulk of Asia’s marine plastic wastes