Wuhan embraces Yangtze River as coronavirus-hit city reopens

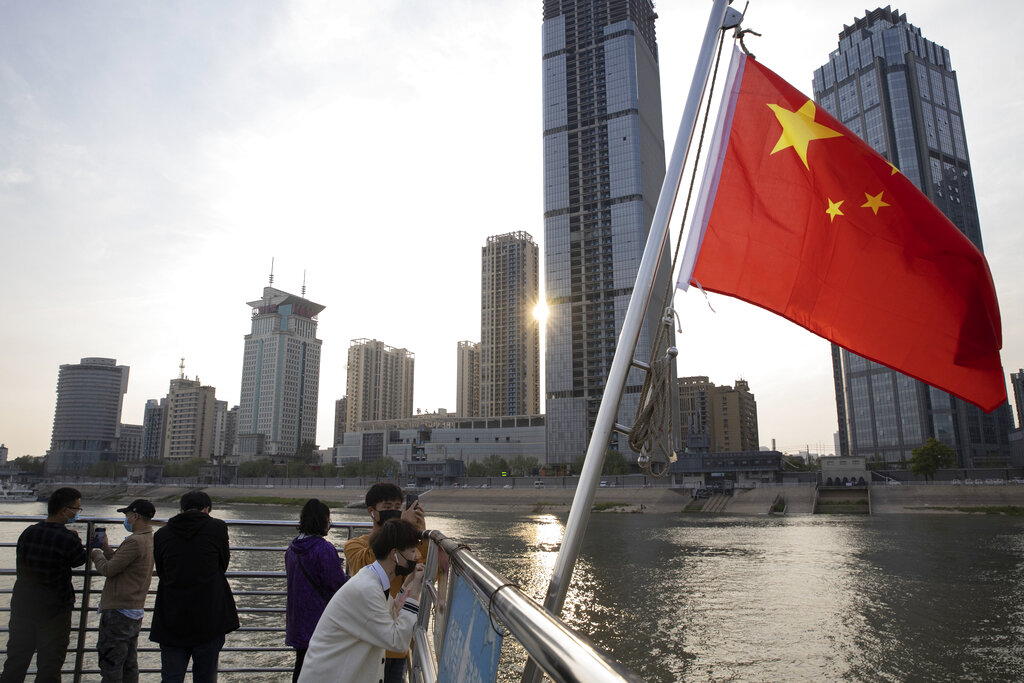

In this April 8, 2020, photo, passengers cross the Yangtze River on a ferry in Wuhan in central China’s Hubei province. The reopening of ferry service on the Yangtze River, the heart of life in Wuhan for more than 20 centuries, was an important symbolic step in official efforts to get business and daily life in this central Chinese city of 11 million people back to normal after a 76-day quarantine ended in the city at the center of the coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

WUHAN, China — Bathed in golden late-afternoon light, Chen Enting snapped a photo of his ticket to commemorate his first ferry ride across the Yangtze River after a 76-day quarantine ended in the Chinese city where the coronavirus pandemic began.

The reopening of ferry services on the Yangtze, the heart of life in Wuhan for two millennia, was an important symbolic step to get business and daily life in this city of 11 million people back to normal.

Wearing goggles, gloves, a homemade mask and a black trench coat, Chen was checked by security guards in protective suits and bought a 1.5-yuan (20-cent) ferry ticket. He boarded with a dozen other passengers, some pushing electric scooters, and found a bench at the front beside a red flag with a yellow sickle. He sprayed the seat with disinfectant before sitting.

“The ferry on the Yangtze River is a symbol of Wuhan’s people,” said Chen, a 34-year-old cost engineer and Chinese Communist Party member.

“The choppy river symbolizes the force of life,” he said, as the sun set behind the Tortoise Mountain TV Tower. “Although Wuhan had such an ordeal, it will flow away just like the river and receive exuberant vitality.”

Article continues after this advertisementWuhan was one of China’s most important centers under inward-looking dynasties that had little interest in foreign trade and carried out commerce and politics over the country’s vast river networks.

Article continues after this advertisementThe city was eclipsed by the explosive rise of Shanghai, Hong Kong and other coastal cities after the ruling Communist Party set off a trade boom by launching market-style economic reforms in 1979.

Today, Wuhan is regaining its status as an economic dynamo as Chinese leaders shift emphasis from exports to developing more sustainable growth based on domestic consumer spending. The city government says more than 300 of the world’s 500 biggest companies, including Microsoft Corp. and Honda Motor Co., have operations in Wuhan to get access to central China’s populous market.

The metropolis was formed from three ancient cities — Wuchang, Hankou and Hanyang — at the meeting of the Yangtze and Han rivers that grew together.

“If you are in Wuchang, you can go anywhere under heaven,” said Ji Li, a University of Hong Kong historian, quoting a traditional saying.

The emperor Kublai Khan visited in the 13th century when China was part of his Mongol empire and Shanghai was a fishing village of a few thousand people.

In the mid-19th century, Wuhan became, along with Shanghai, Tianjin and Qingdao, one of a series of “treaty ports” where China’s Manchu rulers were forced to give Western powers trading privileges and exempt their people from local laws.

A rebellion began on Oct. 11, 1911, in Wuhan that spread across the country and led to the breakup of the Manchu empire and the founding of President Sun Yat-sen’s Republic of China.

The Yangtze’s water is “very sweet,” communist leader Mao Zedong said after he swallowed a mouthful while swimming in the 1950s, according to a report from the time by The Associated Press.

Meandering 6,300 kilometers (3,900 miles) from Tibet’s Tanggula Mountains to the East China Sea, the Yangtze is the longest river in Asia and the world’s third-longest.

It and the Yellow River in the north are the “mother rivers of the nation,” much like America’s Missouri and Mississippi or Eastern Europe’s Danube. It is also the site of the Three Gorges Dam, the world’s biggest hydroelectric project.

The Yangtze stars in countless poems, songs and history-making events, including the third century “Battle of Red Cliffs,” which was fought by one of China’s wiliest strategists, Zhuge Liang. The story, involving armored battleships, has been turned into a traditional opera and a 2008 blockbuster movie directed by John Woo.

Today, Wuhan produces agricultural chemicals, 6% of China’s cars, and components for smartphones, industrial machinery and optical devices for markets in Europe and North America. Skyscrapers loom above parks and ancient temples.

Ships carry goods 700 kilometers (450 miles) downriver to Shanghai by way of Nanjing, another ancient inland city.

Shipping, however, plunged after the coronavirus outbreak started in Wuhan late last year and led to a strict lockdown of the city. Traffic near Wuhan fell by as much as 70%, according to HawkEye 360, a company in Virginia that follows radio communications and ships’ satellite-linked tracking beacons.

Traffic is back to less than half its pre-outbreak level, the company says.

Mao’s face, etched in a giant gold coin, perches atop a stone obelisk in the Bund, the riverfront former center of Western business activity and now a tourist spot. On it is etched a poem by Mao calling for a bridge to be built across the river.

That bridge was finished in 1957, cementing Wuhan’s renaissance as a transportation hub by connecting rail networks in northern and southern China.

That connection is one reason the coronavirus spread so fast.

Authorities have since decontaminated the station, and on April 11, high-speed trains began leaving Wuhan for Beijing again. The ferry system had opened a few days before.

Chen Xianming, a 70-year-old veteran of 26 years in appliance sales, knew that would save him money. Paying for taxis across the bridge had cut into profits.

“We should be thrifty,” Chen said as he secured boxes on a motorized tricycle he uses to make deliveries.

Most of Wuhan is thinking the same way and tightening its belt after factories, restaurants, shopping malls, cinemas and almost every other business except supermarkets were shut for 2 1/2 months. Jittery consumers aren’t spending much. Manufacturing has yet to get back to normal levels.

But the public has returned to the banks of the Yangtze, known in Mandarin as Chang Jiang, or Great River.

Couples wearing masks walk hand-in-hand. Fishermen flick long rods out across the babbling waters. Joggers run past picnickers. People fly kites shaped like butterflies, birds, lanterns and fighter jets. A ship’s horn blares.

“Wuhan reopens,” Chen said. “This is a day of remembrance.”

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.