Diagnosing sexism in Japan’s medical society: ‘No guilt’ over excluding women

TOKYO — It was February 2010. A meeting of Tokyo Medical University’s entrance exam committee was about to take place in a room of a high-rise hotel in Tokyo’s Nishi-Shinjuku district. The fate of examinees was about to be decided at the hotel, which is located close to the university.

A former senior official of the university, who served as an entrance exam committee member at the time, recalled a whispered conversation between Masahiko Usui, 77, a former chairman of the university’s board of regents and then university president, and a clerical staff member in a corner of the room.

“These are the results if we apply this coefficient,” the staff member said.

“Good, we will go with that,” Usui replied.

In the hands of the staff member was a list of the test results of all examinees, with figures such as “0.95” and “0.90.” The senior official assumed that multiple coefficients had been prepared, and Usui was making the final decision as to which one to apply.

Article continues after this advertisementLater on, the former official had the chance to hear from Usui. “If we did the entrance exam normally, women would account for half of admissions. That is why we apply coefficients to the women’s scores,” the former official quoted Usui as saying.

Article continues after this advertisementAn internal investigation by the university discovered that discrimination against women started from 2006, at the latest. This year, the scores of examinees underwent complicated manipulation. First, a coefficient of 0.8 was applied to the scores of the second-round essay test for all candidates to uniformly lower scores. Then 20 points were added to the score of male examinees who were scheduled to graduate from high school that year, as well as those who had graduated from high school within the past two years. Ten points were added to male examinees who graduated from high school three years ago, while no points were added to male examinees who graduated from high school four years ago or more, as well as all female examinees.

The former official outspokenly expressed his feelings, saying, “I have no feelings of guilt. No one would honestly disagree with the opinion that more women would be a problem.”

Females underrepresented

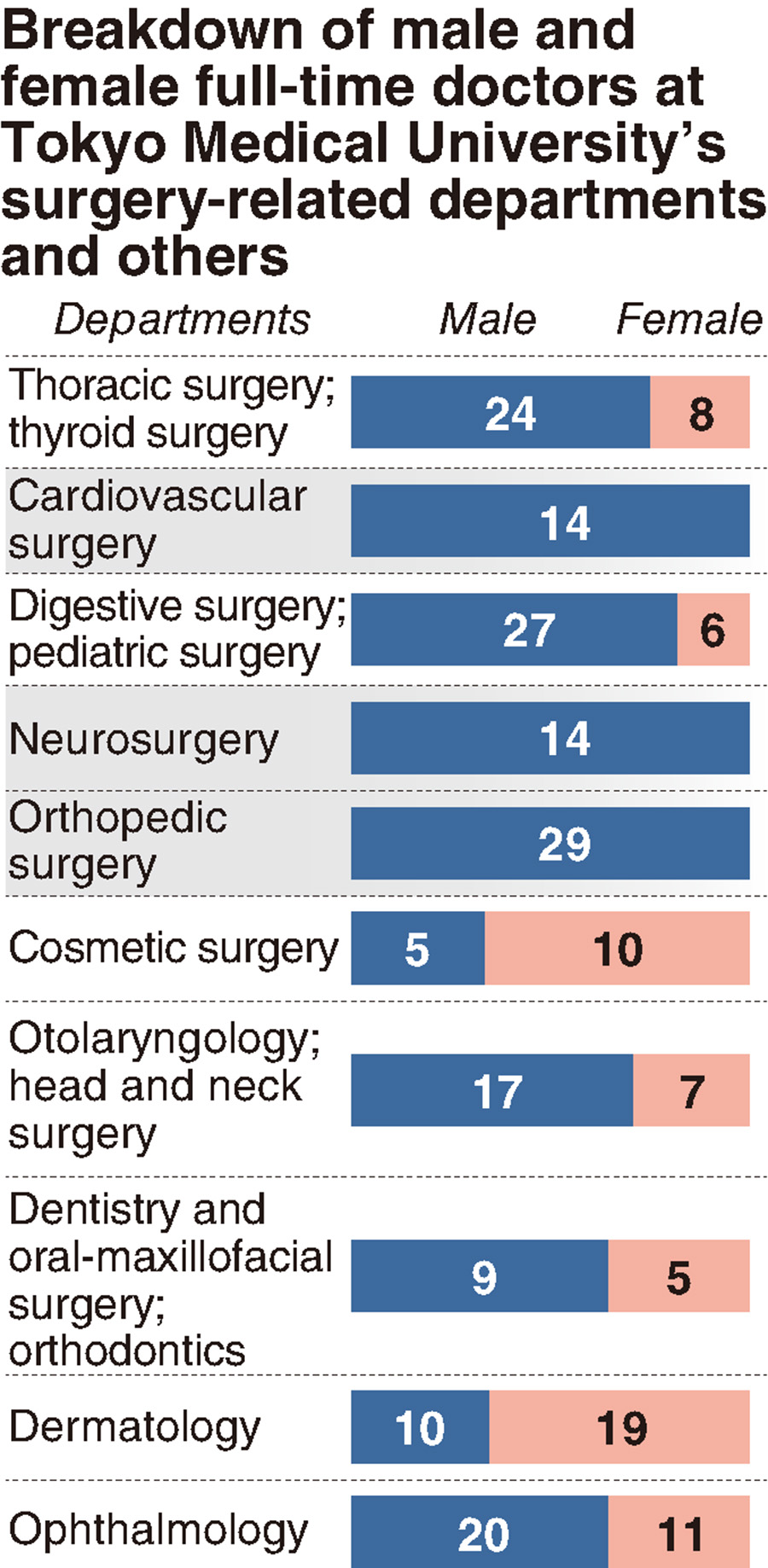

Neurosurgery: 0 percent. Orthopedic surgery: 0 percent. Cardiovascular surgery: 0 percent. These figures denote the percentage of full-time female doctors working at three surgical departments at Tokyo Medical University Hospital as of Aug. 1 — in other words, no women were there.

“Surgery is a totally male-dominated world. There was an atmosphere that keeps women away,” said a female internal medicine doctor in her 50s who graduated from the university.

In surgery-related departments, late-night emergency calls are a regular occurrence, and surgeries can be physically demanding work that extends for more than 10 hours. It can be hardly called an ideal workplace for women who wish to have and raise children.

According to the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry, the percentage of female doctors nationwide — including those working part-time — at the end of 2014 was 20.4 percent. By departments, women accounted for 46.1 percent of doctors in dermatology and 37.9 percent in ophthalmology. However, the figures nosedive in surgery-related departments, such as 5.2 percent in neurosurgery and 4.6 percent in orthopedic surgery.

The overall percentage of full-time female doctors at Tokyo Medical University Hospital is not particularly low, standing at 30.2 percent. However, figures vary widely by departments. “There have long been voices within the university claiming that more women would doom surgical departments,” a senior university official said.

Using ‘trade secrets’

There is a possibility that the unique characteristics of medical schools could also have contributed to discrimination. At private university medical schools, many of the graduates who pass the national examination for medical practitioners join one of the departments at university hospitals. A system has been established in which they then remain at the university hospital or get dispatched to affiliated or related hospitals. Therefore, the entrance exams play the role of a sort of employment exam for the “medical university group.”

The training of doctors is done by each department, and departments decide which hospitals doctors will be dispatched to. There are some cases in which a female doctor leaves work to have a child or for other reasons, so another doctor is newly dispatched to the hospital or dispatching personnel itself is suspended.

A female surgeon worked at a hospital affiliated with Tokyo Medical University for about 1½ years around 2005. She worked from 7:30 a.m. to 10 p.m. six days a week, and also went to work on her days off when she was responsible for inpatients.

The woman said: “The working conditions are poor in surgical specializations, with few women and many of them unmarried. With regards to securing personnel for hospital departments and affiliated hospitals, it makes sense to train male doctors with a lower risk of leaving a job.”

More than a decade ago, a female doctor in her 40s who worked at a national university hospital discovered she was pregnant after she joined the gastrointestinal surgery department. A male professor sounded her out about transferring to a local affiliate hospital, but she declined. “Go somewhere else if you don’t like it,” the professor told her, so she moved to the staff department of a different university hospital.

“How do you drop female test-takers?”

“We do all kinds of things, like making the math questions more difficult.”

A former official who held an important post at Tokyo Medical University until a few years ago revealed that devising ways to reduce the number of women passing entrance exams was a routine topic of conversation at meetings attended by presidents and chairmen of private universities with medical schools.

At one such meeting, the former official asked a staff member at a university known for its low percentage of women what their “secret” was, but the staff member was evasive, only saying, “I can’t tell you that — it’s a trade secret.”

“It is the same at every university. We are of no use to the public if we are swayed by sentimentality,” the former official said clearly.

Breaking with the past?

At an emergency briefing for students at the university on Aug. 9, Acting President Keisuke Miyazawa, 60, apologized to students, saying, “We have caused great disappointment and distress among students.”

He also made a promise, saying, “The university will make every possible effort to create a positive working environment for women.”

At a press conference two days earlier on Aug. 7, the university explained that a string of improprieties was committed under the leadership of Usui, former chairman of the board of regents. Tetsuo Yukioka, 67, an executive regent, pledged to “root out discrimination.”

The university has released information on the general entrance examination for next year on its website. Out of the 171 candidates who passed this year, 30 were women (excluding those who took the National Center Test for University Admissions).

Several university officials have the same opinion that the number of women will definitely increase next year.

However, negative opinions about female doctors persist on the front line of hospitals.

“If the number of women who pass increases, there will be fewer capable people in the hospital departments, and heavier burdens will surely be on those on the front line,” one university official said, showing his true feelings. “The tide of gender equality is a real headache, but all we can do for the time being is push through by saying, ‘The discrimination was something the former chairman did of his own accord.’”

It seems there will not be any preparation to make a break with the past.