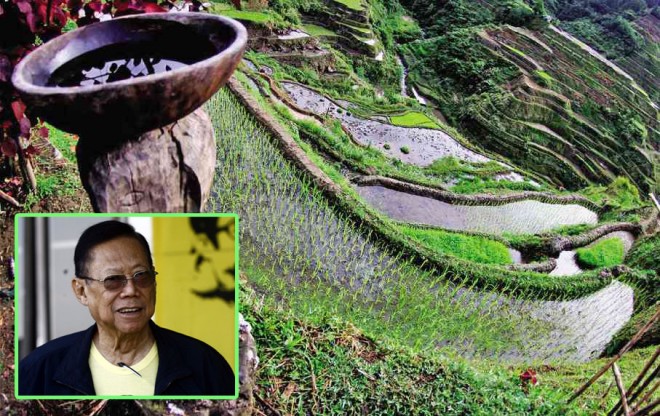

Butz Aquino key role rarely told in Cordillera peace pact

BAGUIO CITY, Philippines—Shortly after the ouster of strongman Ferdinand Marcos in 1986, Agapito “Butz” Aquino went to the upland town of Sadanga in Mountain Province for the first time to convince elders there that they no longer needed to fight the government.

But Aquino was too excited and arrived early when the community was not yet ready to receive him so he had to return to complete his task, said Fernando Bahatan Jr., author of the yet-to-be-released book “Struggles for Cordillera Autonomy.”

Aquino was the official emissary of his sister-in-law, then President Corazon Aquino, who opened all government channels to encourage rebel groups to talk peace after Marcos was ousted, Bahatan said.

But the name of Butz Aquino, who died on Monday at age 76, rarely crops up today whenever the Cordillera story is retold to younger generations.

Accounts of his role in the Cordillera peace talks, which were part of Bahatan’s draft, were also cut for brevity when the book’s final version was approved by its financier, the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process.

Door to peace

But people who fought for Cordillera autonomy remember it was Aquino who opened the door to peace in the region, Bahatan told the Inquirer on the telephone on Wednesday.

Aquino’s chief task was to build confidence with the Cordillera fighters who distrusted the government, said Sadanga Mayor Gabino Ganggangan, who once served as a political officer for slain rebel priest Conrado Balweg.

Aquino also took back to Malacañang all he learned about the Cordillera tribal peace processes to hasten the government’s negotiations with Cordillera communities, Bahatan said.

Due to Aquino’s efforts, Mrs. Aquino motored to Mt. Data in the Mountain Province on Sept. 13, 1986, to exchange tokens with Balweg and implement a sipat (cessation of hostilities between government troops and Cordillera rebels).

The sipat allowed both sides to begin negotiating peace, leading to the issuance of Executive Order No. 220 on June 15, 1987, which created the Cordillera Administrative Region by reuniting upland provinces that were separated in the 1960s with various regions.

“[Balweg] was first to respond to Mrs. Aquino’s call for peace,” Bahatan said.

Mrs. Aquino had sent her brother-in-law to meet with elders in Sadanga, a natural convergence point for Balweg’s political leaders and elders in the region.

Patient, good-natured

“Butz was a very patient and good-natured man. He arrived when the community was practicing tengaw, a period when no one in the community works and when no one can enter or leave the community. It’s a planting ritual we practice before harvest. But it meant no strangers may enter the village,” Ganggangan said.

“We had to let him stay in a school outside the village. When the ritual day ended (sometime between the end of April and the start of May in 1986), the community allowed Butz in, and he was surprised to see not just the whole community assembled but delegates from other provinces, like Kalinga,” he said.

It was also a very angry crowd, Bahatan recalled, because some of the problems confronting the Cordillera provinces at that time involved government projects introduced by Marcos.

Development projects

The Cordillera’s struggles began with government-sponsored projects like the Chico River Dam in Kalinga, said Dr. Steven Rood, country director of the Asia Foundation, who spoke at an autonomy forum here in June.

“It begins not with a political upheaval but because of a violation of local control over resources. That’s the whole point of an ili (community). When the government messes with that [right], it ignite[s] resistance,” said Rood, a political scientist who used to teach at the University of the Philippines Baguio.

The effort to understand Cordillera tribal dynamics was a particularly difficult undertaking for strangers like Aquino, Ganggangan said, “but it needed to be done because the [Cordillera] fighters had too much pent-up rage against the government.”

“They did not trust the government and the government could not offer any other way to prove they were not out to trap and arrest Father (Conrado) Balweg. So we offered instead our bodong (peace pact) process, and Butz brought that to Cory,” he said.

Closure agreement

The sipat lasted until Mrs. Aquino’s son assumed the presidency in 2010.

In 2011, the Aquino administration concluded the negotiations began in 1986 with a June 14 closure agreement that granted development projects for upland communities in exchange for disarming and disbanding Balweg’s militia, the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army.

RELATED STORIES

Cordillera militia gets DAP projects

Rebel priest’s son now an Army soldier