House in literary classic defies time

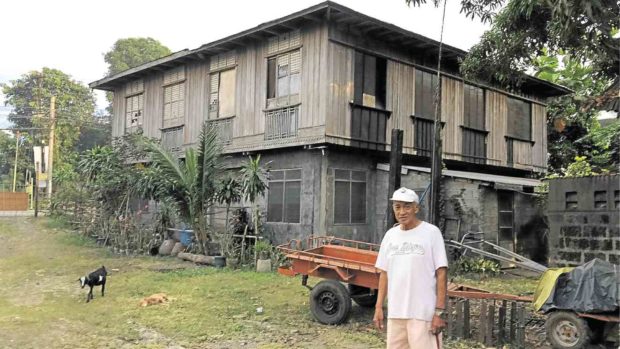

The house in Bauang town in La Union province where Ilocano writer Manuel Arguilla was born is now home to the author’s nephew, Jose Sonza. —PHOTOS BY YOLANDA SOTELO

BAUANG, LA UNION—Papaya trees in bloom are no longer found in the sprawling yard of the house where acclaimed Ilocano writer, Manuel E. Arguilla, was born. Long gone, too, is the camachile tree in front.

Arguilla mentioned the trees in his 1940 short story, “How My Brother Leon Brought Home a Wife,” as well as the wooden house that, to this day, has defied the test of time.

Dogs run free and goats graze in the yard beside the house. At the back, a deteriorating barn stands and a path leads to a wide rice field stacked with hay that would be fodder for the family carabao for months.

“This is the house where Leon, in the story, brought home his wife,” says Jose “Pepito” Arguilla Sonza Jr., 73. Sonza is the son of Arguilla’s sister, Aurelia, and lives in the house with his family.

Arguilla was the second of four children of Crisanto Arguilla, a farmer and carpenter, and Margarita Estabillo, a potter. The eldest was Aurelia while the third and fourth were Salvador and Gualberto, respectively.

Article continues after this advertisementSonza admits that he has no recollection of his uncle. “He died when I was only a year old,” the nephew says.

Article continues after this advertisement“How My Brother Leon Brought Home A Wife” is one of the most famous works of Arguilla, an Ilocano writer in English, a patriot and a martyr.

His stories, written when he was between 22 and 29 years old, were compiled in a book, “How My Brother Leon Brought Home a Wife (And Other Stories)” published by the Philippine Book Guild in 1940. The collection won first prize in short story category in the First Commonwealth Literary Contest in 1940.

Arguilla’s stories were almost always set in his village, Nagrebcan, here.

During World War II, Arguilla joined the guerrillas. He was captured and executed by Japanese soldiers in August 1944. He was 33.

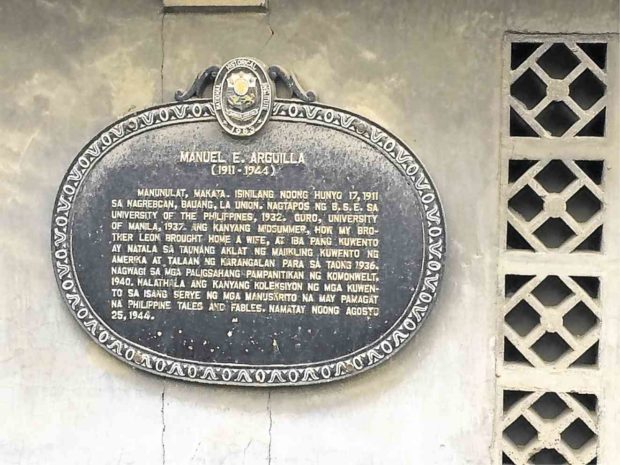

In front of the Arguilla house is a barely visible marker put up by the National Historical Institute of the Philippines and detailing the writer’s profile. The house could have been built during the American occupation when Arguilla was born on June 17, 1911.

Sonza recalls his grandmother telling him and his cousins that their uncle had an uncanny way of dodging farm chores. “He would bring books and continuously read these while his siblings were working. My grandmother would tell Arguilla’s siblings not to bother him as he was studying,” Sonza says.

He also remembers playing with his friends on the same cart that Leon and his wife, Maria, used in going home in the story. But the cart is long gone, too.

“Leon” could have been taken from the name, “Manuel,” or simply Noel spelled backwards.

Maria could be “Auntie Pinay,” or Josefina, the wife of Salvador. It was Salvador who actually brought home a wife to Nagrebcan.

But a cousin insisted that it must be Lydia, Arguilla’s wife, because the story refers to Ermita, Manila, where the couple had lived. Lydia was also a writer and an art curator.

Sonza showed the rooms of the wooden house, saying they were called “Narra” and “Santol.”

“[Narra room] could be where Maria met Leon’s father for the first time, as depicted in the story,” he says.

He says his grandfather built a wooden house with concrete posts at a time when most houses in the village were made of nipa and bamboo.

“He was a carpenter but was also a contractor, so he had money for the house. [He used] tanguile wood (for the floor, door posts and trusses) while the walls were ipil wood. The windows were made from capiz shells,” Sonza says.

A rocking chair now at Manila Hotel came from the Arguilla house while the writer’s papers and documents, all in a chest, were taken by the National Press Club, supposedly to be brought to the National Library.

The house was occupied by top officials of the invading Japanese forces during World War II. It also once served as an office of the Central Bank.

Former Mayor Mary Jane Ortega of San Fernando City says the local government offered to rent the second floor of the Arguilla house for a museum. Nothing came out of the talks, however.