Vessel monitoring, key to fight vs plunder of PH seas, faces new problem

MANILA, Philippines—The Vessel Monitoring System (VMS), which is seen to help in sustaining marine resources by keeping track of commercial fishing vessels, is facing a new challenge.

In a Dec. 14, 2022 letter to Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) officer-in-charge Demosthenes Escoto, the BFAR was asked to clarify what happens next as the Integrated Marine Environment Monitoring System (IMEMS) contract with a British solutions provider has already expired.

The VMS forms part of the IMEMS, which BFAR had said seeks to effectively monitor and control marine resources in the Philippines, especially through the detection of illegal activities.

But there’s a problem.

In the Dec. 14, 2022 letter to BFAR, sent by lawyer Ma. Neseira Ailah G. Tuquero, the bureau was told that based on the Terms of Reference contained in IB No. 2018-19, “delivery of goods is required within 4 years reckoned from the date of receipt of the Notice to Proceed and in accordance with the project implementation schedule provided in the bidding documents.”

Article continues after this advertisementThe Proceed Date indicated in the Notice of Award was indicated as Dec. 4, 2018 while the Contract End Date was indicated as Dec. 4, 2021, so “based on the award, the contract has already expired for over a year.”

Article continues after this advertisement“Even assuming for the sake of argument that the expiration date as stated was a typo, the same has also expired,” the letter read. “This also has a direct bearing on the satellite services subscription which applies only for the whole duration of the project.”

As stated in the letter, the expiration of the contract will also necessarily result in consequences such as, but not limited to, the forfeiture of the performance security or extension thereof along with other effects as may be provided in the various Termination Clauses under the Terms of Reference, particularly in cases of default.

Because of this, BFAR was also asked to make public any actions or resolutions or any notices and communications in relation to the expiration of the contract with the SRT Marine Systems Solutions Ltd.

Controversial

Last year, a complaint was filed at the Office of the Ombudsman against then BFAR director Eduardo Gongona, Escoto and Hansel Didulo, who were then Department of Agriculture (DA)-BFAR bids and awards committee chairpersons, and Simon Tucker and Richard Hurd, officials of the solutions provider.

The complaint, which was filed by lawyer James Mier Victoriano, asked the Office of the Ombudsman to charge the respondents with violations of Sections 3(e), 3(g), and 3(j) of Republic Act No. 3019 or the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act; Sections 30, 34, 65(c), and 65(d) of RA No. 9184 or the Government Procurement Reform Act; and Section 23.6 of the Revised Implementing Rules and Regulations of RA No. 9184.

READ: BFAR director, 4 others face graft complaint over fishing vessel monitoring system project

This, as the initial invitation to bid in 2017 for the IMEMS Project Phase II stated that the project was to be funded by the French Republic and through a loan agreement. The initial invitation to bid had an Approved Budget for the Contract (ABC) of P1.6 billion.

Victoriano said the loan agreement required that the bidder must be either a French national or possess a joint venture agreement with a French national, and that the goods must be of French origin.

However, “despite the requirement, SRT participated in the bid and was declared by DA-BFAR to be eligible and eventually won the bid.”

Victoriano said it was clear that DA-BFAR did not comply with the conditions provided in the initial invitation to bid and would have continued with the award if not for the disapproval by the French government.

Because of the disapproval by the French Republic, BFAR then sought the approval of the National Economic Development Authority to cancel the loan agreement and proceed with the procurement for the project using local funding.

Looking back, it was in October 2018 when BFAR conducted the last bidding with an ABC of P2.09 billion. SRT was eventually awarded the contract to equip fishing vessels with VMS transceivers.

Fight for VMS implementation

But before the complaint was filed in March 2022, the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) and fishers’ groups clashed on whether BFAR should still implement the VMS despite a court decision that voided its legal basis.

Looking back, fisherman Ruperto Aleroza stressed that “the sea gives us our livelihood and food [so] we need to take care of it.”

He made this appeal in light of efforts to fully implement the VMS then, a system which the BFAR said was expected “to enhance the capacity of the government to monitor fishing operations and enforce laws in Philippine waters to achieve long–term sustainability of our resources.”

The appeal came in the wake of an order by then Solicitor General Jose Calida to BFAR and National Telecommunications Commission (NTC), which were among agencies tasked with implementing VMS, to comply with a court decision voiding Fisheries Administrative Order (FAO) No. 266.

READ: Gov’t requires monitoring devices in all fishing vessels

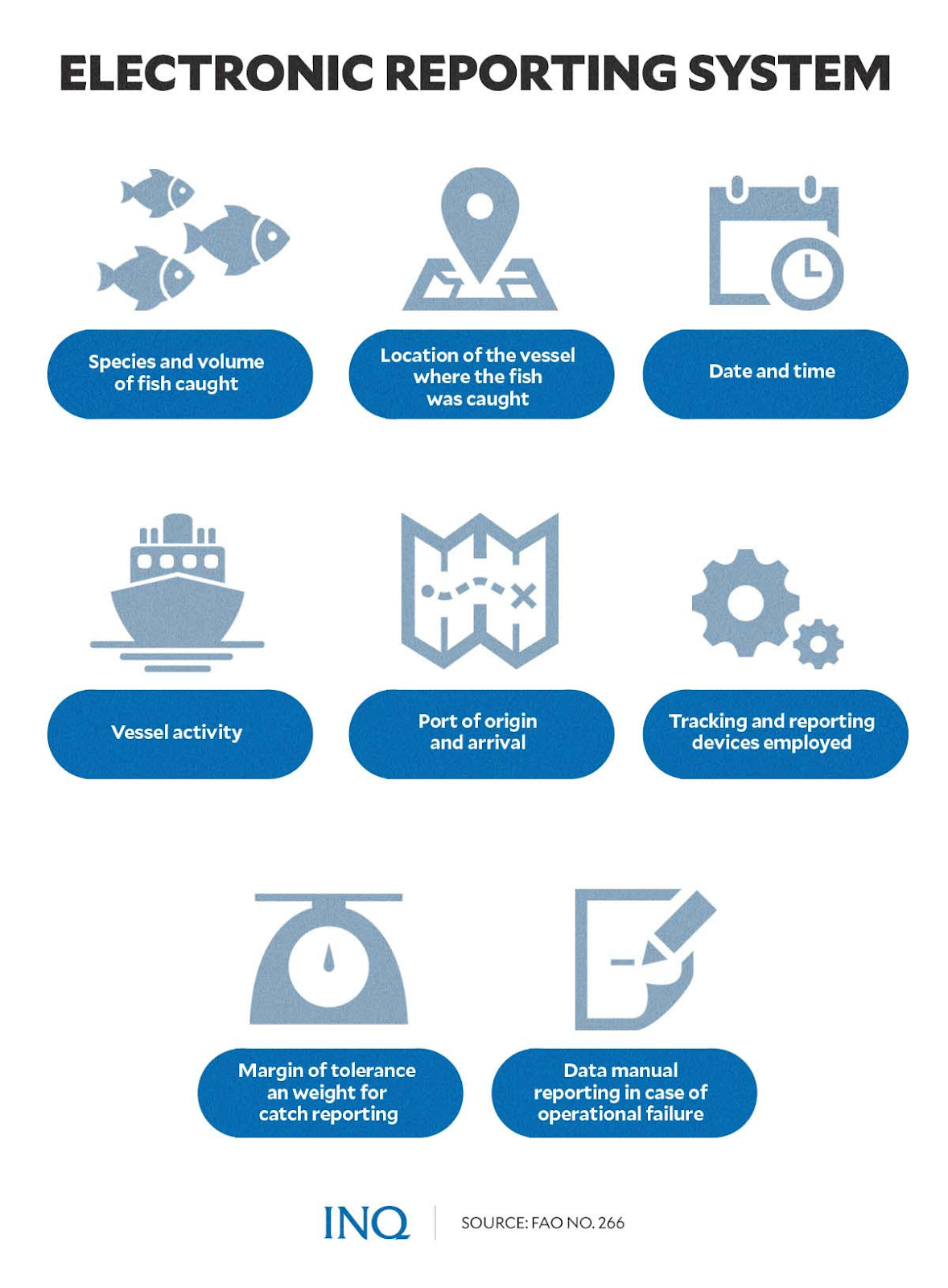

FAO No. 266 was signed by then Agriculture Secretary William Dar on Oct. 12, 2020 to list down rules and regulations in the implementation of the VMS and installment of Electronic Reporting System (ERS) in commercial fishing vessels operating in the Philippines.

But on June 1, 2021, the Malabon City Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 20 declared FAO No. 266 as void, saying it’s not constitutional.

Fishing firm’s complaint

The decision granted the petition, filed by the Royale Fishing Corp., Bonanza Fishing and Market Resources and RBL Fishing Corp., which said that Sections 14 and 119 of Republic Act No. 8550 should not be implemented.

The provisions of the Fisheries Code of the Philippines, as amended by Republic Act 10654, was implemented by FAO No. 266. But the fishing corporations said these are not constitutional.

Section 14 provides that DA-BFAR should establish a monitoring, control and surveillance system in coordination with local government units, fishing councils, the private sector and other agencies involved in the fisheries sector.

READ: Advocacy group wants DA-BFAR to promulgate rules to protect local fisherfolk

This was to make certain that the Philippines’ fisheries and aquatic resources are “judiciously and wisely utilized and managed on a sustainable basis and conserved for the benefit and enjoyment exclusively of Filipino citizens.”

Section 119 provided that no municipal, commercial or distant water fishing vessel shall engage in fishing without complying with the VMS promulgated by the DA-BFAR in coordination with local governments.

The fishing corporations, which are engaged in commercial deep-sea fishing, however, said the provisions violated their constitutional right to privacy and protection from unlawful searches.

They said FAO No. 266 also violated the equal protection clause and the law it seeks to implement, saying that the release of FAO No. 266 violated their right to participate in the decision-making process.

This was the reason that last Jan. 17, some fishing corporations asked the RTC to cite Gongona in contempt for alleged disregard of the decision which prevented the implementation of FAO No. 266.

READ: Fishing firms want BFAR, NTC cited for contempt for defying court order

The OSG said as the RTC made permanent its preliminary injunction, and unless the Supreme Court (SC) issues any injunctive writ, the BFAR and NTC should desist from implementing FAO No. 266.

READ: OSG to BFAR: Follow court decision on unconstitutionality of monitoring systems

Its new legal opinion was different from its earlier stand that BFAR and NTC can still implement FAO No. 266 and direct commercial fishing operators to install the VMS.

For lawyer Gloria Ramos, vice president of Oceana, the recent reversal in the position of the OSG on the implementation of FAO No. 266 is baffling, “to say the least.”

Fisherfolk’s fight

The group Pangingisda Natin Gawing Tama (PaNaGat) Network said BFAR and NTC should stand firm in implementing FAO No. 266. They likewise condemned the “continued violations committed by commercial fishing vessels.”

PaNaGat and Oceana said that Republic Act 10654, which amended the Fisheries Code of the Philippines, prohibits RTCs from issuing injunctions, as provided by Section 134.

The prohibition against the enforcement of environmental laws was likewise reiterated in the SC’s rules on environmental cases, and the Office of the Court Administrator’s Circular No. 87-2016, they said.

For Ramos, the installation of VMS in commercial fishing vessels is a requirement of Republic Act 10654. This requirement, she said, will strengthen the monitoring, control and surveillance system required by the law.

Oceana said based on BFAR’s record last month, the implementation of VMS has already reached 50 percent, or 1,526 of the 3,077 total commercial fishing vessels with license to operate in Philippine territorial waters.

The VMS are expected to track the location, course and speed of fishing vessels in real time to collect data and information that would help manage the Philippines’ fish and other marine resources, according to the BFAR.

When FAO No. 266 was signed in 2020, it directed that vessels weighing 3.1 to less than 30 gross tons (GT) should have a BFAR-approved vessel monitoring system (VMS) installed within one year.

Vessels weighing 30 GT or more, FAO No. 266 said, should immediately install a VMS.

ERS will be for the recording and transmission of catch data, like species and volume of fish caught, location of the vessel where the fish are caught, vessel activity and the vessel’s port of origin and arrival.

BFAR said the ERS was expected to provide these minimum data in real time:

- Species and volume of fish caught

- Location of the vessel where the fish was caught

- Date and time

- Vessel activity

- Port of origin and arrival

- Tracking and reporting devices employed

- Margin of tolerance and weight for catch reporting

- Data manual reporting in case of operational failure

The National Fisheries Monitoring Center was tasked with hosting the system of all Philippine-flagged fishing vessels within Philippine waters, which include the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), high seas and EEZ of other nations.

Why is VMS needed?

For fishermen and Oceana, the VMS is essential, especially for the protection of municipal waters that are critical to the recovery of the ocean from decades of overfishing, illegal fishing and declining fish catch.

Republic Act No. 10654 designates 15 kilometers from the shoreline as municipal waters––reserved for the preferential use and access of municipal and artisanal fisherfolk pursuant to the social justice provision of the 1987 Constitution.

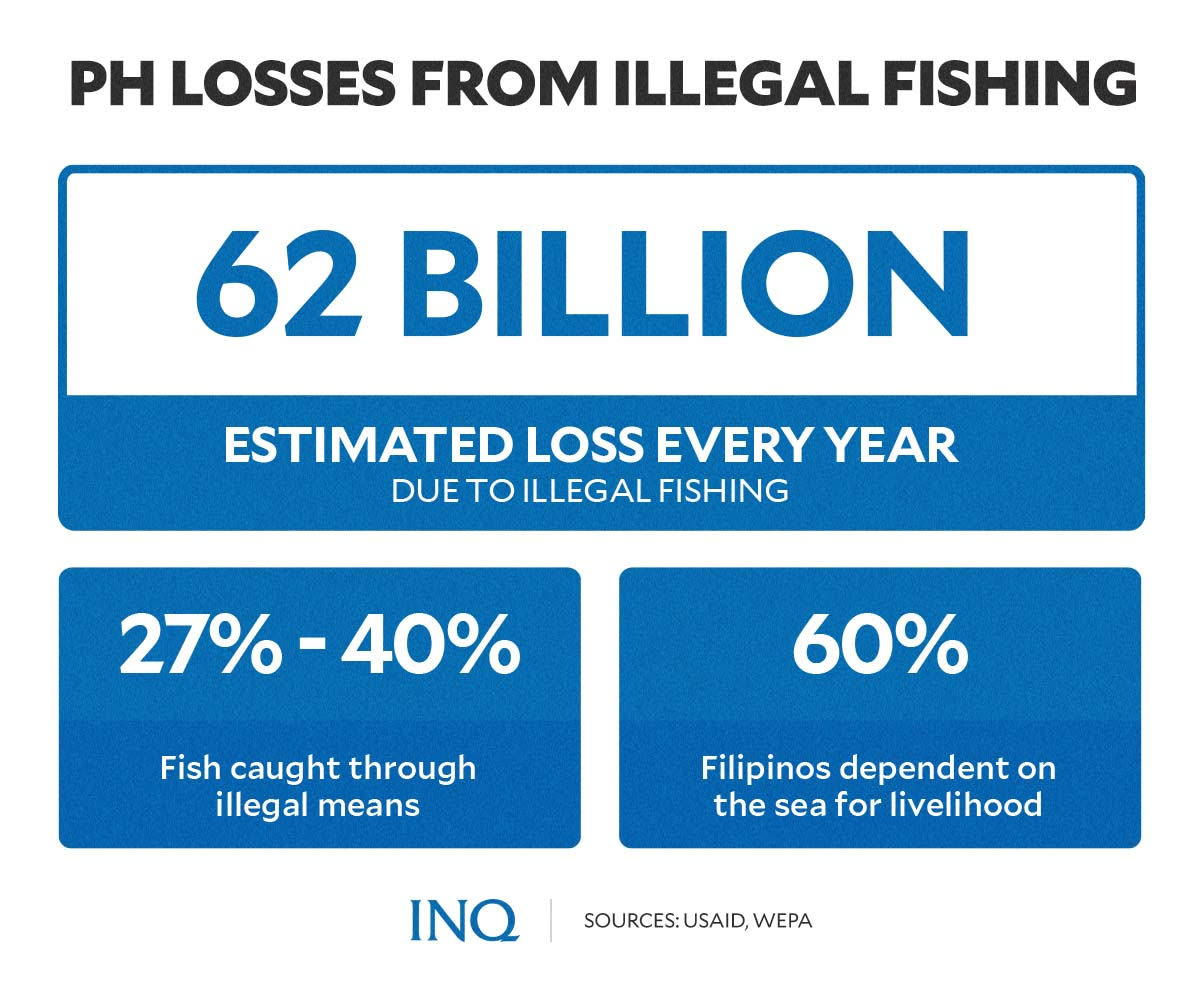

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) said in 2020 that the Philippines has been losing an estimated P62 billion yearly because of illegal fishing.

It revealed that in the Philippines, illegally caught fish amounted to 27 percent to 40 percent of all fish caught in 2019. The USAID study quantified illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

The USAID found that 30,000 vessels are still not registered while commercial fishers do not report haul reaching almost 422,000 metric tons of fish each year.

It said these show the immense impact of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in the Philippines’ marine ecosystem.

This, as 60 percent of Filipinos live in coastal towns and highly depend on the sea for livelihood.

For Oceana’s Ramos, “Illegal fishing has remained a problem even if we have the law. The intrusion of commercial fishers in municipal waters caused this problem of overfishing.”

“Our fish stocks are continuously decreasing at an alarming rate. This has caused unjust suffering to poor artisanal fisherfolk that’s why the government has to abide by its mandate to protect the coastal communities’ livelihood and the food security of the Filipino people,” she said.

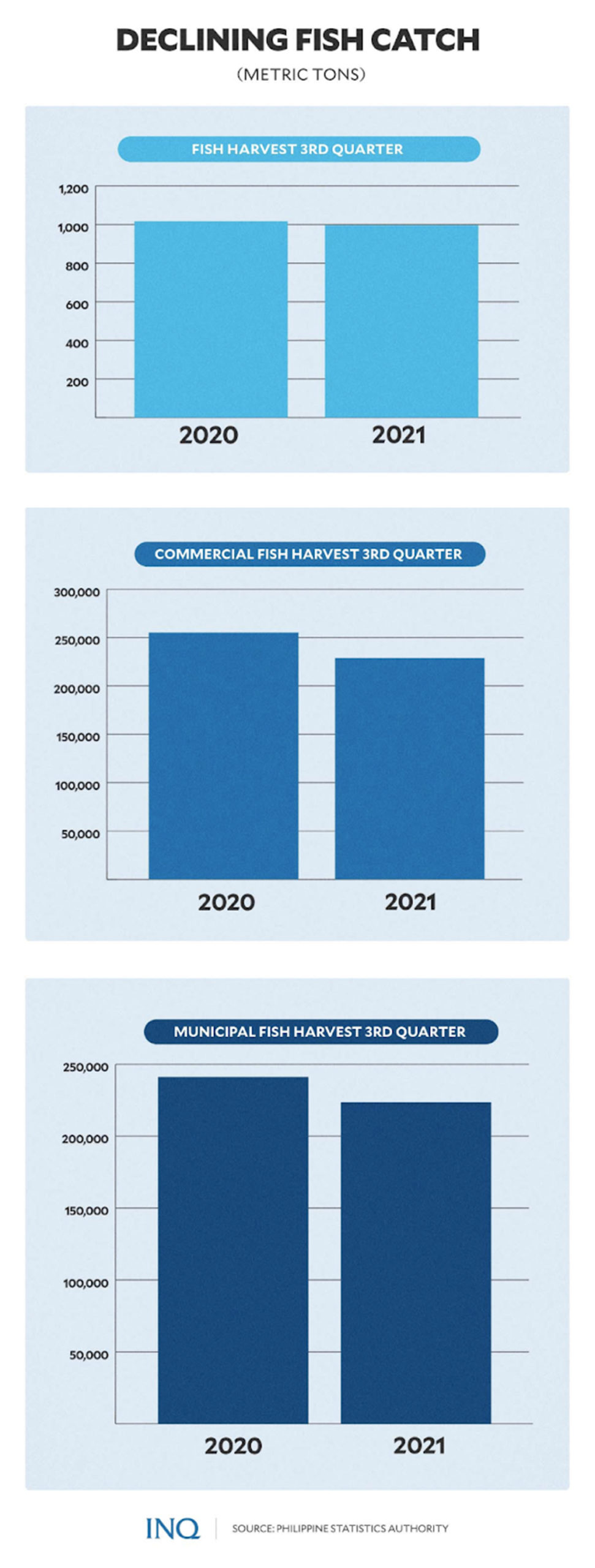

Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority revealed that in the third quarter of 2021, total fisheries production went down by negative 2.1 percent from 1,016,460 metric tons in 2020 to 995,470 metric tons in 2021.

The volume of production of commercial fisheries likewise fell by negative 10.3 percent from 255,110 metric tons in 2020 to 228,780 metric tons in 2021.

Marine municipal fisheries had a harvest of 223,500 metric tons, a negative 7.3 percent growth from the 2020 level of 241,130 metric tons.

BFAR said the VMS likewise ensures the safety of fishermen through a tracking device that would monitor the vessel’s location in instances of accidents and disasters.