Pandemic dug deeper pit for PH poor—study

FILE PHOTO: In this photo taken on December 8, 2020, street dwellers queue up for free food distributed by Catholic religious order Society of the Divine Word (SVD) in Manila. Charities are struggling to meet the ever-growing demand for food as millions of families go hungry across the country where Covid-19 restrictions have crippled the economy and thrown many out of work. Ted ALJIBE / AFP

MANILA, Philippines—Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Filipino families relying on microenterprises to survive were already in the precipice of hunger and income loss.

A study by researchers at Ateneo de Manila University (AdMU) found that most may have already been pushed off the cliff.

Data from the study fell in stark contrast with those being painted by the government, which offer a rosy picture even as the numbers drew widespread gloom.

In his Christmas Eve message last year, President Rodrigo Duterte urged Filipinos to see that there was still hope left in the middle of darkness, poverty and suffering because of the pandemic.

READ: Hope even in darkness, poverty and suffering, Duterte tells Filipinos

A study, titled “The Impact of COVID-19 and the ECQ on Low-Income Households in Microenterprises: Analysis of the ASA Philippines Client Survey”, provided a deeper probe on the impact of the pandemic and government response to it.

Article continues after this advertisementIt was prepared by professors of the AdMU Department of Economics and covered low-income households during the first enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) in 2020.

Article continues after this advertisementPoverty worsened

Associate Professor Geoffrey Ducanes, Professor Leonardo Lanzona and Associate Professor Philip Arnold Tuaño discovered that most of the 97,000 low-income households in microenterprises surveyed in May 2020 “suffered severely from the lockdown.”

A severe decline in earnings became the biggest impact among the respondents, who are clients of a microfinance institution.

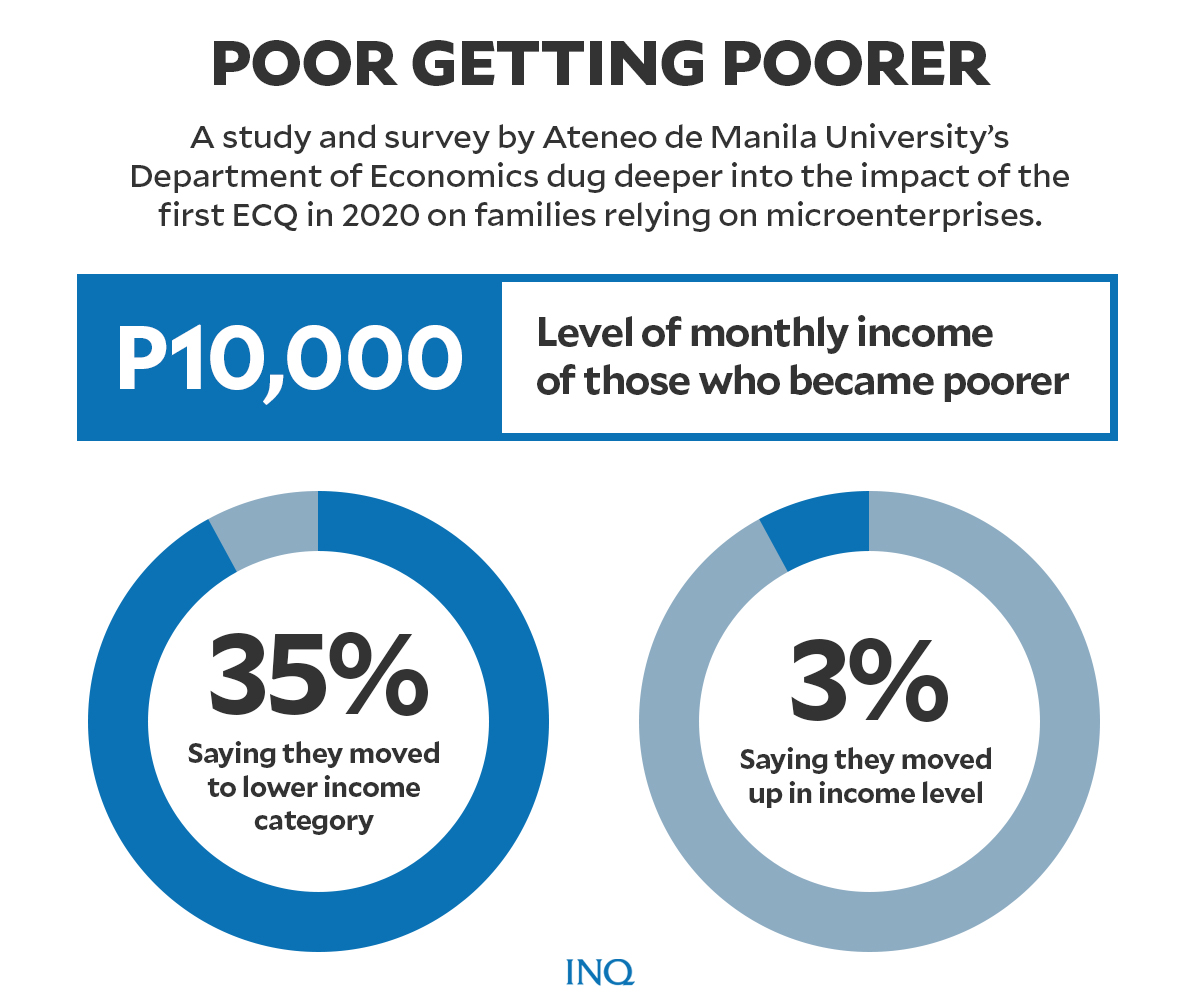

During the 2020 ECQ, 35 percent of respondents in all 17 regions covered by the survey said they moved to a lower-income category—P10,000 and below—while only 3 percent moved to a higher-income category or up to P100,000 or P100,000 and above.

Graphic by Ed Lustan

The researchers, however, noted that 54 percent of the households were already in the lowest income category prior to ECQ, making it impossible for them to move to a lower-income category. Meaning they’ve already hit rock bottom.

“If the sample is limited to households who were at least in the second income level pre-ECQ, then 76 percent reported moving to a lower-income category during the ECQ,” the study stated.

Separate surveys on the 2020 ECQ by the Social Weather Stations (SWS) reflected the same results.

In December 2020, around 48 percent of Filipino families rated themselves as poor while 36 percent think they are borderline poor.

READ: Almost half of Filipino families feel they are poor, latest SWS survey says

In a survey also by SWS conducted from April to May 2020, 49 percent of families described themselves as poor and 33 percent viewed themselves as borderline poor.

READ: Only 17% of Pinoy families feel they’re not poor, 49% say they are — SWS

More empty stomachs

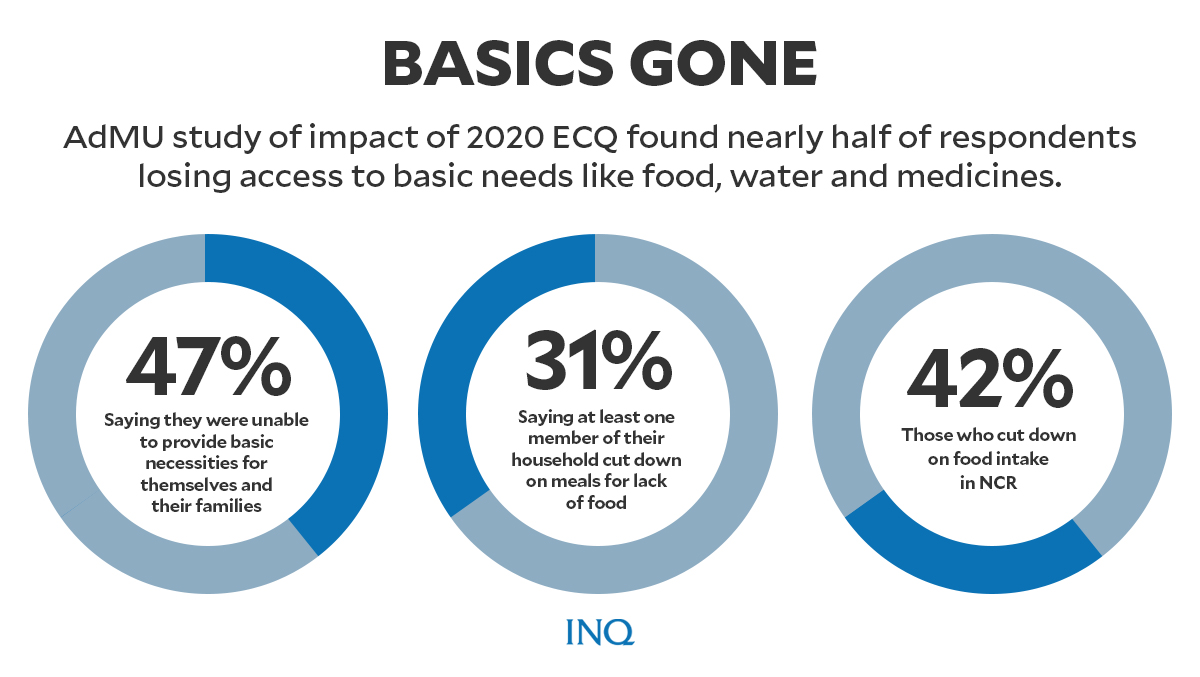

Aside from increased poverty among AdMU study respondents, almost half or 47 percent of households included in the survey said they were unable to provide enough basic needs—food, water and medicines—for their families during ECQ in 2020.

Graphic by Ed Lustan

Most who reported they were unable to provide enough needs to themselves and their families came from the National Capital Region (NCR), Calabarzon, Caraga, Western Visayas, Northern Mindanao and ARMM.

“Only 39 percent said they were able to provide the same as before, and 14 percent said they were able to provide more than enough,” the study read.

Moreover, 31 percent of the surveyed household reported: “at least one member eating less than they wanted during ECQ because they lacked food.”

The share of those who ate less during the 2020 ECQ was high in NCR—42 percent—and Caraga—39 percent.

At least 26 percent said they did not only eat less prior to the survey period, but they also experienced it twice. Another 26 percent experienced it three times.

A huge 67 percent of the 42 percent who experienced eating less than they wanted in NCR said they experienced it twice.

In addition, 12 percent said they experienced having no food to eat in the house during ECQ 2020.

The portion was especially high in Caraga with 20 percent and Northern Mindanao and Davao del Sur both with 17 percent saying they had no food at all during last year’s ECQ.

“Among those who reported experiencing having absolutely no food to eat in the house during the ECQ, 43 percent experienced it at least twice,” the survey read.

“By region, the share of those who experienced this at least twice is especially high in NCR at 62 percent (of the 13 percent who experienced having absolutely no food),” it added.

Last month, SWS released a survey showing that the country’s average hunger rate in 2020 reached an all-time high of 21.2 percent amid the coronavirus pandemic.

READ: SWS survey: PH hunger rate climbs in new all-time high amid pandemic

How families cope

While majority of the sample households—around 89 percent—said they received some form of aid during the 2020 ECQ, around 73 percent said they got assistance in form of relief goods—typically rice and canned goods.

“To be able to provide for their family during the ECQ, 38 percent of the sample households, as a primary answer, said they either got another job or tapped into other sources of income (such as pension), 27 percent said they spent less, and another 27 percent said they borrowed money,” the study found.

Some also made adjustments to their livelihood during the ECQ, due to poverty and hunger.

Around 23 percent said they closed operation, 19 percent have cut their operating hours, 4 percent changed their livelihood, another 4 percent added other sources of income, and 2 percent had laid-off workers.

“By region, the share of those who closed operation was especially high in NCR (35 percent), Region 3 (32 percent), and Region 4A (31 percent),” the researchers noted.

More needs to address

The adjustments, however, were not permanent solutions for the sample households.

Graphic by Ed Lustan

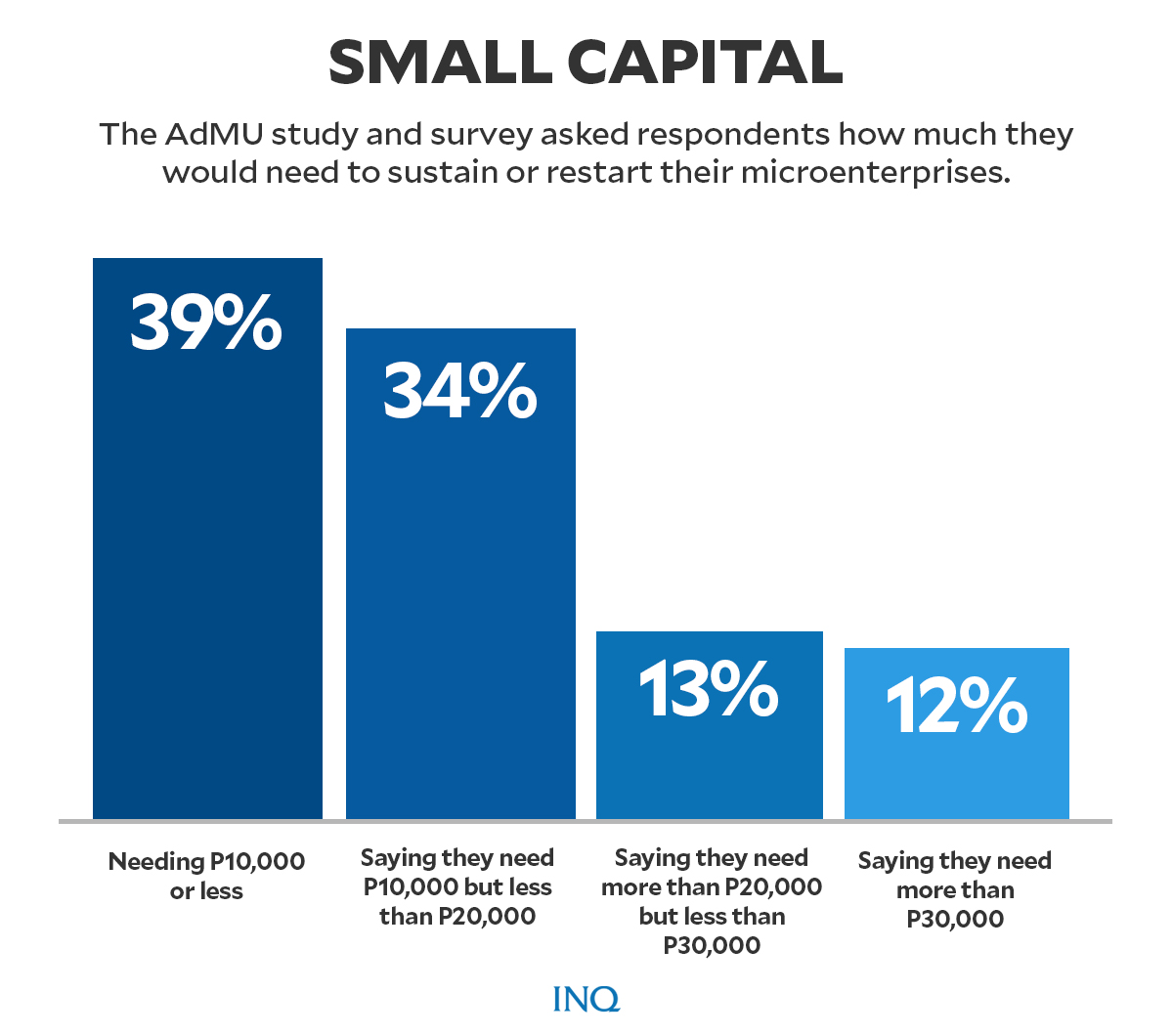

“When asked how much capital they would need to bring their families out of their predicament and back to their pre-ECQ condition, 39 percent said they would need P10,000 or less, 34 percent said they would need more than P10,000 but less than P20,000, 13 percent said they would need more than P20,000 but less than P30,000, and the other 12 percent said they would need more than P30,000,” the survey results said.

“Overall, the amount of capital the household enterprises said they would need is quite small, possibly reflecting the amount of loans they have historically received from microfinance institutions rather than their actual needs, and also possibly reflecting an underestimation of how long the economic difficulties arising from the pandemic would last,” the researchers said.

Majority, around 86 percent, said they would source capital by borrowing from a microfinance institution, a little over 12 percent said they would use their savings, while three percent said they will find capital from other sources.

Still, many respondents worry about being able to maintain their business post-ECQ. At least 74 percent said a primary hurdle could be decline in sales, 14 percent mentioned the stoppage of production or supply, 9 percent said lack of capital, while 2 percent said loan and bill payments.

The issue with ayuda

To aid Filipino families amid the pandemic, the national government distributes a lifeline—called ayuda or cash aid.

According to the AdMU study, 17 percent received ayuda from local government units (LGUs) and different government agencies while nine percent from the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps).

Still, around 19 percent of the total survey respondents said they were not using any money transfer service—a crucial mode of receiving ayuda.

On the other hand, one-third of the respondents did not have any household member registered in LGU offices, an important requirement for getting cash aid.

“The share of unregistered household enterprises and members is high in both developed and underdeveloped areas, but especially in Region 3 (48 percent), ARMM (43 percent), NCR (41 percent), and Region 4A (41 percent),” the study said.

Missed targets

A separate report, also published by the Ateneo de Manila University, said the Duterte administration has failed to meet its own targets in addressing the pandemic.

While official data depicted a rosier picture—lower poverty and higher education rates through the years–reality on the ground reflected the opposite.

“President Duterte may be very popular and official poverty rates may be going down, but these do not erase the reality that many Filipinos continue to feel and experience poverty and hunger—especially under the pandemic,” the researchers said.

“President Duterte did not use his political capital where it is supposed to matter: in the everyday lives of Filipinos,” they added.

For example, while the country saw lower poverty rates under the Duterte administration—16.7 percent in 2018—more households in general (48 percent) rated themselves as poor under the Duterte presidency, according to Social Weather Stations (SWS) data cited in the study.

READ: Gov’t missed its own COVID-19 targets – Ateneo study

TSB

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.