Poor fend for themselves amid gaps in gov’t pandemic response

MANILA, Philippines—The strict lockdown in Metro Manila was scheduled to end on Friday (Aug. 20) but uncertainty prevails over what would come next—another round of enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) or a less restrictive measure.

READ: IATF weighs between ECQ extension and MECQ in Metro Manila

While the next quarantine measure in Metro Manila after Aug. 20 is uncertain, one thing has been clear since the start of the COVID catastrophe in 2020—its impact had been “profound and adverse” on the poor.

READ: Metro Manila mayors defer decision on NCR community quarantine status to IATF

Bea Rodriguez, a widow, lives in a household of 12 people in a resettlement area in Towerville, San Jose del Monte City, Bulacan. She lives in a small house with her children and their families so she can “closely watch over her family.”

In 2020, as the government first imposed ECQ, she lost one month’s worth of income, prompting her to think of ways she can make ends meet for her family, a household that consumes at least three kilos of rice per meal.

READ: Pandemic in PH: Misery beyond numbers

“I hope people in government act as if they were in our situation,” said Rodriguez who, before the pandemic, had been depending on her salary from Igting, or Maigting na Samahan ng mga Panlipunang Negosyante sa Towerville Inc., a social enterprise based on clothing production.

Igting sewers went back to work a month after the lockdown prompted them to temporarily stop operations. PHOTO FROM UP CIDS REPORT

Rodriguez, 61, was one of the Filipinos trying to struggle against poverty who had been engaged by the Program on Alternative Development of the University of the Philippines’ Center for Integrative and Development Studies (UP CIDS) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) in a research program.

Article continues after this advertisementEduardo Tadem, Ph.D. said the report on the program presented five cases—urban poor community, women’s micro social enterprise, an indigenous people’s community and a school for indigenous children and youth.

Article continues after this advertisementCOVID punishment

Filipinos, especially in the midst of a crisis, say, “Who else will help us except for ourselves?” In Filipino, “Sino pa ba ang magtutulungan kung ‘di tayo rin?”

This was the reality for millions of people feeling the direct impact of the COVID pandemic since 2020. Most felt neglected while government restrictions left them in the dark and fighting their way through the crisis.

Rodriguez, for instance, had to rely on relief programs from her son’s employer and money transfers from relatives as the group she works for, Igting, was forced to close for a month amid COVID protocols.

In 2020, the government had a provision to provide assistance to families who “have no incomes or savings to draw from, including families working in the informal economy and those who are not presently recipients of the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps).”

Rodriguez said the government assistance, through the Social Amelioration Program (SAP), could have helped her family but delays in actual aid distribution prompted her and her family to find ways to survive on their own.

READ: Pandemic sinks PH poor even deeper

“Three weeks after the declaration of the community quarantine, the first of the three rounds of food packs from the local government arrived. It contained five kilos of rice, eight cans of sardines, and four packs of instant noodles,” said the UP CIDS report.

It added, “The first of the two payouts of the cash aid (amounting to P6,500) was made in the third week of May.”

The same was experienced by the Ayta Mag-Indi community in Porac, Pampanga—indigenous individuals in barangays Camias and Planas whose ordeal showed how health crisis-related policies “further exacerbate the already marginalized status of indigenous peoples in Philippine society.”

When the community first learned of the strict lockdown, “they tried to build their understanding of the pandemic from the fragments of information they obtained,” the UP report said.

The only support that the indigenous groups had, the report said, were the Ayta Barangay Health Workers who were likewise “not fully informed” about the health crisis.

The residents said the government was not even the first to provide them with basic necessities: “The very first effort to provide them assistance came from the graduate students of University of the Philippines who were their longtime partners in community development projects and initiatives.”

READ: PH economy sinks deeper into recession

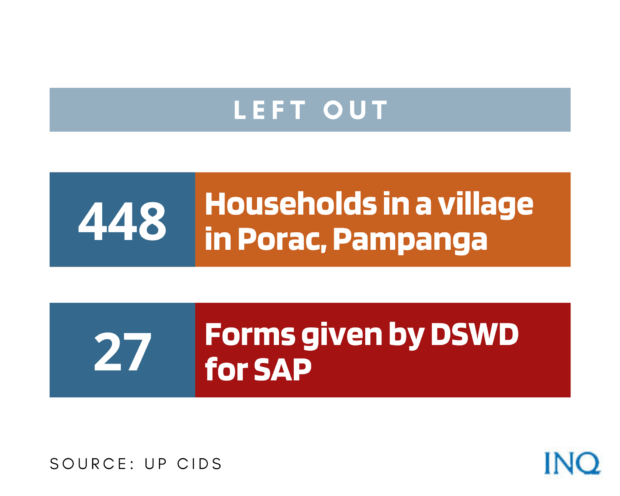

In a village, there were 448 households, but when the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) gave out forms for the SAP, only 27 were given to the community.

The report said the tribal chieftain tried to negotiate with the barangay captain to at least provide for half of the families in the barangay, but to no avail— 90 percent of the families in the village were “left out of the longed-for promise of assistance by the national government.”

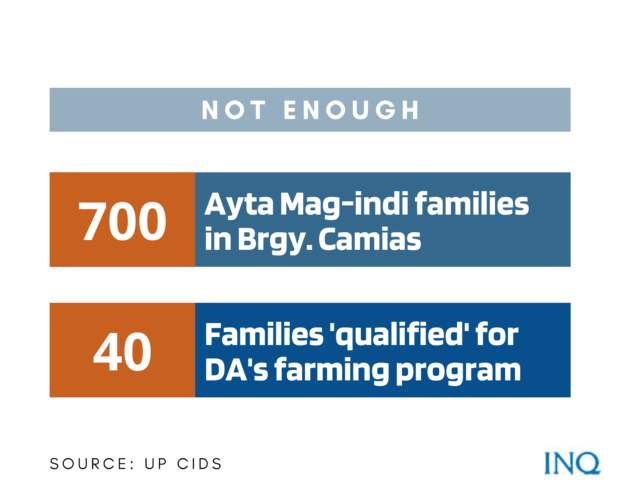

In Barangay Camias, families were asked to take part in a program of the Department of Agriculture on communal farming, but out of 700 families in the village, only 40 families were said to be “qualified,” leaving 90 percent of the population with nothing.

Four months after the lockdown was imposed, the report said the community was excited after hearing that the DSWD will provide “more assistance,” but only 70 hygiene kits were provided by the department.

“You can liken this to a disaster. The COVID-19 virus caused the pandemic. But the responses to address the pandemic, or lack thereof, is what brings on the disaster to the people,” said Benny Capuno.

Resilience and initiatives

In Quezon City, as the strict lockdown was imposed in 2020, the Alyansa ng mga Samahan sa Sitio Mendez, Baesa Homeowners Association, Inc. (ASAMBA) “devised their own ways of mobilizing effectively in response to a health crisis.”

ASAMBA members organize food items for the distribution in their community. PHOTO FROM UP CIDS REPORT

The group’s women leaders served as the community’s frontline workers with tasks ranging from restricting residents’ mobility to implementing basic health protocols. The group said they also had to work on food rations because “many went hungry.”

The report said the essential element in ASAMBA’s implementation of lockdown was not “imposing draconian and punitive-based measures to get people to comply.” Instead, a collective leadership from community workers made it possible for residents to comply.

In Bulacan, the Bantay Kalusugan Pampamayanan, despite the struggles they experienced since the start of the health crisis, was “resolute in continuing its role as health service provider in the community.”

Its activities involved checking, monitoring, and documenting the health of community members, but the health workers likewise engaged themselves as first responders and health informants.

In Pampanga, while only 40 families were officially listed to benefit from the program of DA, the Ayta Mag-indi collectively decided that the produce and harvest from the program will be made available to all families in the village.

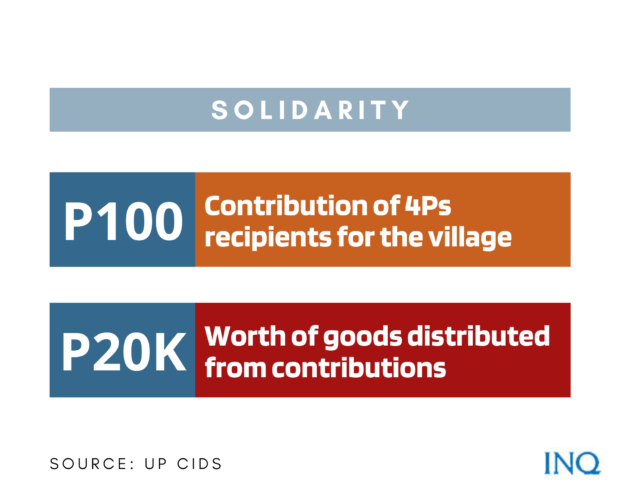

The 4Ps beneficiaries also contributed P100 each (in cash or in kind) and were able to generate P20,000 worth of essential needs that were distributed to families who were not recipients of the government program.

Community leader Violeta Abuque said P100 may seem as a very small contribution, but it definitely showed solidarity and the community’s capacity to look after their own welfare.

The workers of Igting also found ways to cope with the health crisis as the enterprise decided to open again after CAMP Asia, Inc. approached them to produce 100,000 face masks which allowed workers to earn P300 to P900 per day.

Lockdown miseries

Several communities struggled, especially on finances, as the government was “delayed” or “inconsistent” in its delivery of basic services for Filipinos highly impacted by the crisis.

However, for most residents, it was not the only reason for their struggles because COVID-19 restrictions likewise made their lives harder.

In Barangay Minuyan Proper in San Jose del Monte City, Bulacan, residents were allowed to go out only twice a week – Wednesdays and Saturdays—which means that a family needs to have “enough” money to purchase goods that would last for days.

This, the report said, was not good for poor families, especially for households with heads who lost jobs because of lockdowns.

In Metro Manila’s Bakwit Schools (alternative schools) for lumad children, who are fleeing militarization in Mindanao, the lockdown was a “nightmare”.

Gov’t needs to respond

As Filipinos sink deeper in dire straits amid the pandemic, the UP researchers said the government should consider “new and additional measures to arrest the deteriorating conditions.”

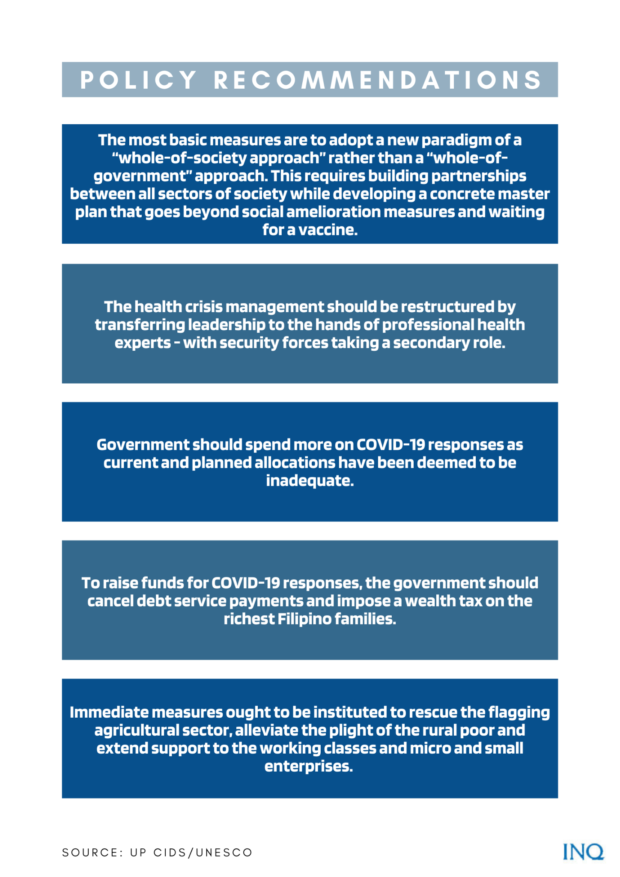

Last year, the researchers presented the following five policy recommendations to representatives of eight Philippine government offices:

- The most basic measures are to adopt a new paradigm of a “whole-of-society approach” rather than a “whole-of-government” approach. This requires building partnerships with all sectors of society while developing a master plan that goes beyond social amelioration measures and waiting for a vaccine.

- The health crisis management should be restructured by transferring leadership to the hands of professional health experts—with security forces taking a secondary role.

- Government should spend more on COVID-19 response as current and planned allocations have been deemed to be inadequate.

- To raise funds for COVID-19 responses, the government should cancel debt service payments and impose a wealth tax on the richest Filipino families.

Immediate measures ought to be instituted to rescue the flagging agricultural sector, alleviate the plight of the rural poor and extend support to the working classes and micro and small enterprises.