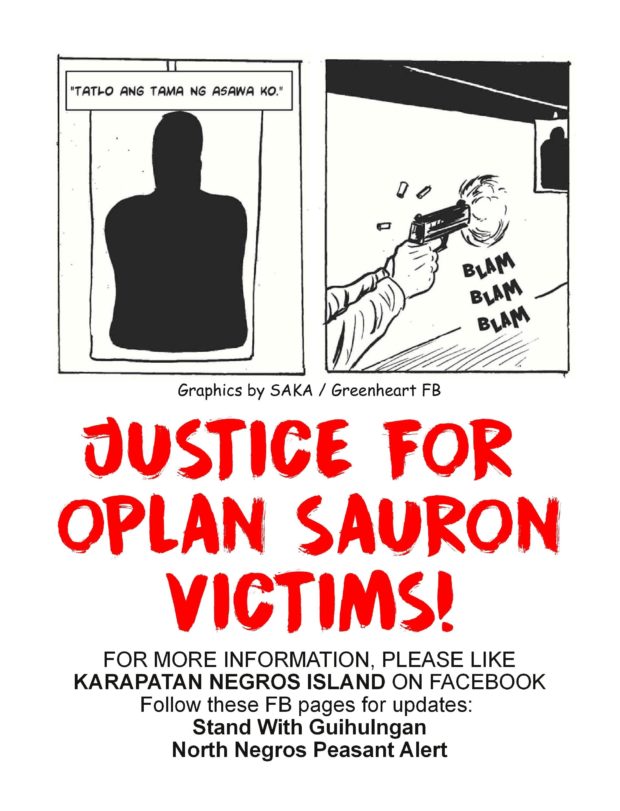

Negros Oriental killings illustrated in comics

STORYTELLING MEDIUM The Concerned Artists of the Philippines has commended three illustrators for telling the story of the killing of 14 farmers in Negros Oriental in drawings, in a show of solidarity with the victims’ families.

MANILA, Philippines — The illustrated stories started to appear on the internet two days after the Negros Oriental killings.

The first told in drawings the testimony of Carmela Avelino, the widow of farmer Edgardo Avelino, who was killed by police in a weapons raid in Canlaon City on March 30.

The second illustrated the testimony of McKallif “Jun” Arapoc, brother of Steve Arapoc, a farmer who was also slain by police in a similar raid in Manjuyod town on the same night.

And the third depicted the testimony of Leonor Avelino, widow of Ismael Avelino, brother of Edgardo Avelino, whom policemen also killed in the Canlaon raid.

14 killed

Article continues after this advertisementIn all, 14 farmers were killed in the military-backed police operations in Canlaon City and Manjuyod and Santa Catalina towns.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Philippine National Police claimed the farmers were shot because they fought back while officers were serving search warrants on them.

The authorities said the farmers were members or sympathizers of the communist New People’s Army (NPA) and had participated in attacks on security forces in the province.

But a fact-finding team formed by several human rights and farmers’ organizations found last week that the 14 had been summarily executed.

Emiliana Kampilan, award-winning author and illustrator of “Dead Balagtas Tomo 1: Mga Sayaw ng Dagat at Lupa,” which won both the National Book Award and the Madrigal Gonzalez Best First Book Award, illustrated the testimony of Leonor Avelino.

In an interview with the Inquirer, Kampilan said she was disgusted and angry with the police and the military and felt it was her duty as an artist and activist to present Avelino’s story in a compelling visual form.

Written by poet-activist

Like Julius Villanueva, who illustrated Carmela Avelino’s testimony, and Josel Nicolas, the illustrator of Arapoc’s account, Kampilan worked with poet-activist Angelo Suarez of Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo (Saka) to develop the digital artworks.

Suarez worked using the findings of the investigative team from Stop Killing Farmers Network.

He turned the findings into narratives that the illustrators could work with.

“Comics is a visual mode of storytelling. It combines the strength of words and images, so it’s really two ways of expounding on the truth,” Kampilan said, adding that it was a powerful medium to spread information.

In a statement issued on Sunday, the Concerned Artists of the Philippines commended Villanueva, Nicolas and Kampilan for their solidarity with the slain farmers’ families.

“We commend the efforts of our fellow Filipino storytellers to tell the stories of the marginalized to the public via [comics]. We congratulate them for their effective use of the medium, delivering compelling artistry and political acuity in the fight for genuine land reform and against fascist rule,” the group said.

Villanueva, author and illustrator of “Life in Progress,” said comics was “much more potent in disseminating ideas and stories” compared to the written form.

He said his goal in drawing the testimony of Carmela Avelino was to generate compassion for the plight of the farming family.

“Usually, when some people read about this, they’re quick to label the victims as rebels or NPA. I wanted to show them as people, as a family who have just suffered a really horrible injustice,” Villanueva said.

Nicolas said he wanted people to see what happened and to be informed of events that were physically distant from their own realities.

Suarez said comics was attractive to his group because a lot of details from the witnesses’ testimonies were visual.

He said two more such works were under preparation.

Nicolas said he used his art for activism. In 2015, he said he drew a comic strip about the Kentex factory fire that killed 74 workers in Valenzuela City based on a work by Suarez.

“I’ve always valued communication in art, [and its potential for] social service,” Nicolas said.

He said that although he was “very angry” as he drew the story, he wanted readers to understand that they just could not be blind to what was happening in the country.

“With anything I do, I want people to feel some gut reaction … I want people to feel as helpless as the people they are reading about,” he said

Sympathy

Villanueva said he had a similar goal.

“I wanted the comics to generate sympathy for the plight of these farmers, to make their story reach people who otherwise wouldn’t have heard of it. I think it has been successful in that end,” Villanueva said.

Kampilan has heard her work labeled as propaganda, but to her what matters is that she has been able to help shed light on the plight of Negros farmers.

“I feel we succeeded in doing that. How people will act on the rage or sadness they feel after reading the comics is another thing,” she said.