Tarlac town keeps history in war museum

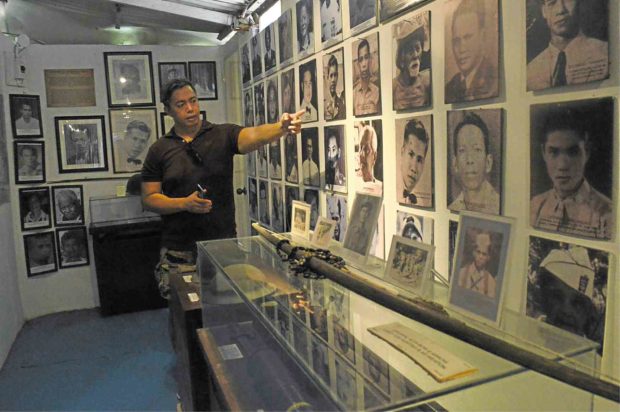

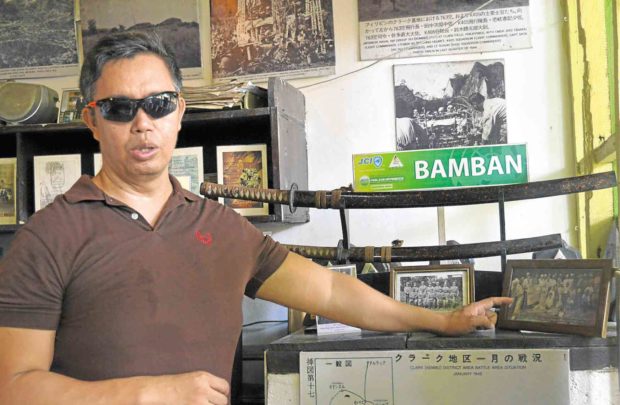

HONORING WAR VETS Former migrant worker Rhonie dela Cruz used his savings to put up the Bamban Museum of History in honor of his grandfather and other Filipinos who fought the Japanese during World War II. —PHOTOS BY MARIA ADELAIDA CALAYAG

BAMBAN, Tarlac — Rhonie dela Cruz has broken off from the path usually taken by Filipino migrant workers.

Instead of retiring, traveling, farming or starting a business, he chose to spend his money to establish the Bamban Museum of History (BMH) in this town of his birth.

Dela Cruz, 47, said he was inspired by the legacy of his paternal grandfather, Macario, who served in Squadron 101 that became Company A of the Bamban Battalion of the South Tarlac Military District under Capt. Alfred Bruce.

Macario’s son, Bartolome, fought as a member of Bruce’s unit in the Battle of Bamban Hills. Another son, Domingo, saw action with the US Army’s Philippine Scouts.

Two relatives of his mother, Brigida Cauguiran, served in the Philippine Scouts.

Patriotism

“I know the history of Bamban. There should be a place to showcase its history. The memories should not be lost to the next generations. I want to keep history alive,” Dela Cruz said.

The museum’s strength lies not only in Dela Cruz’s perseverance to keep the endeavor going since 2005 but also because Bamban had a very rich story of how it thrived during the war, from December 1941 to September 1945.

Savings

The town also represented patriotism when its residents, including the Aeta indigenous people, fought Spanish and American colonialism.

In Dela Cruz’s estimate, eight of 10 residents had one or more relatives who fought in World War II and who should be honored.

The Bamban Museum of History keeps photographs, documents, personal belongings and other memorabilia of hometown heroes.

Dela Cruz, an accountancy graduate, built the BMH on a 220-square-meter lot he bought from his father, Rufino.

Seed money came from his savings while working for National Chemical Fertilizer in Saudi Arabia from 1993 to 1998, and for a metal parts fabrication plant in Japan from 2000 to 2001.

“Sasadsad ke (I’ve been trying to sustain it),” he said in Kapampangan. But it was a challenge since the museum did not get any funding support from the local or national government.

It does not charge an entrance fee as well, and relies instead on donations of friends, volunteers and guests.

Battle sites

Since March, Ernie Legaspi, who runs a local cable television station and a water refilling shop, has been contributing monthly to pay for the museum’s electricity.

Dela Cruz’s other friends pitch in time and labor as cleaners and tour guides.

Before putting up and curating the BMH, Dela Cruz founded Bamban Historical Society (BHS) in September 1999.

LIBERATING BAMBAN This 1945 photograph from the US National Archives and Records Administration shows American soldiers entering Bamban from Lingayen, Pangasinan, to flush out Japanese forces in the town with the help of local guerrillas.

BHS heeded the example of the late Angeles City historian Dan Dizon. Its 25 founding members identified 12 battle sites, undertook research on the Battle of Bamban Hills, and installed initial markers on nine historical spots in the town.

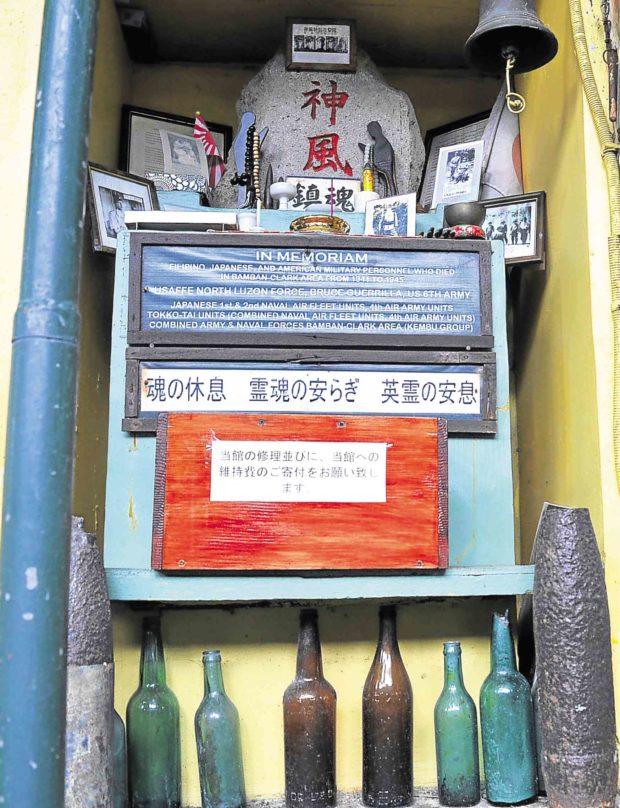

The museum receives many Japanese visitors, both young and old. A number of them come to pray for those who died in the war, which is why an altar has been put up near a row of Philippine, American and Japanese flags.

Artifacts, such as military uniforms, helmets, guns, bloodied flags and aircraft machine guns, are on display.

The BMH has many photographs and documents, which are reproductions from the US National Archives and Records Administration as well as from relatives of veterans. It also holds original pieces, such as a set of 25 black-and-white pictures collected by Pvt. Joseph Bryant Bedingger of the 11th Cavalry during his tour of duty between 1902 and 1903.

Austere

Joan Skiff, wife of Pvt. Marshall Skiff of the US Army 38th Division, was among the BMH’s first visitors and donors.

The museum remains an austere facility. Much of it is makeshift and less equipped to handle the task of preserving its more vulnerable items. But it still gives a bird’s eye view of how Bamban hurdled war’s devastation.