Jihadists rise in Mindanao

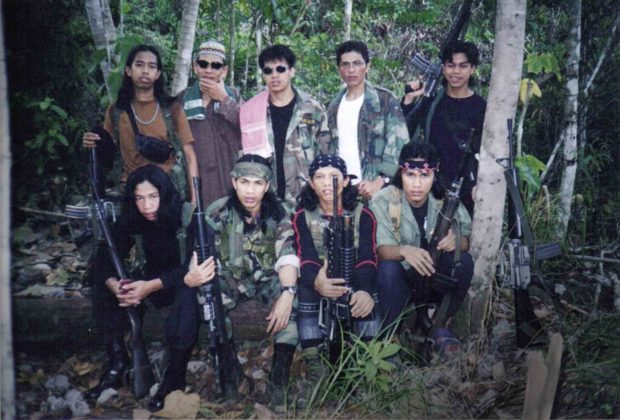

JUNGLE LAIR Abu Sayyaf bandits, shown in this file photo in their jungle stronghold, have linked up with other Islamist terrorists in Mindanao.

(Editor’s Note: The writer served as chair of the government panel in peace talks with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front during the Aquino administration. She is also a political science professor at the University of the Philippines.)

In the last 50 years, the Philippine government has been trying to forge peace with Moro insurgent groups. But for every step forward, it moves two steps back. In between these steps, a new generation is born, the world changes, and new armed groups are formed.

The eve of the 21st century ushered a qualitatively new wave of jihadism in the country. A slew of new Philippine-styled Islamist armed groups emerged. Although linked by kinship and historical ties to the Moro liberation fronts formed in the 1970s, these new groups espouse a different ideology.

If the older generation of rebels struggled for the right to self-determination and self-government of the Moro people, the new militant groups want an Islamic state that is part and parcel of a global caliphate.

The former fought the Armed Forces of the Philippines for the recognition of Bangsamoro as an ethnopolitical identity; the latter is mounting a violent, intolerant, hegemonic religious jihad against nonbelievers.

Article continues after this advertisementUnlike their elders, the 21st century Islamists have no patience for a long drawn-out guerrilla war. Rather, they want quick, explosive results achieved through indiscriminate acts of violence like bombings, kidnappings and beheadings. Unabashedly, they raise funds through criminal activities.

Article continues after this advertisementBorn in the age of information and communication technology, these militants are social media-savvy. They are networked with global jihadist movements whose modus is to operate as a conglomerate of self-sustained, self-radicalized, decentralized cells.

JI connection

The oldest of these homegrown Islamist formations is the notorious Abu Sayyaf group (ASG). Formed by younger, foreign-educated cadres of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in Sulu and Basilan in 1991, their reported first links with al-Qaida was through a foreign foundation.

In 2001, the ASG connected with operatives of Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), an al-Qaida network in the Southeast Asian region. Despite factionalism and descent to banditry in Sulu, the Basilan group led by Isnilon Hapilon appears to have kept intact the Islamist agenda of Abdurajak Janjalani, the ASG founding father. In July 2014, Hapilon pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) group.

Had the administration of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo not restarted peace negotiations following the all-out war launched by the previous administration of President Joseph Estrada against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), it is possible that the MILF would have taken the same path as the ASG.

After all, JI operatives were already in MILF training camps since 1994. In 2001, however, the MILF agreed to hold fresh talks with the government on the basis of their original Bangsamoro agenda.

In mid-2000, the MILF moved to decisively cut ties with the ASG and JI. Their leaders were purged from MILF areas in central Mindanao. JI stuck close to the ASG in Basilan and Sulu.

Had the talks under the nine-year Arroyo administration reached fruition, another Islamist group—Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF)—would not exist today. However, the peace talks suffered a major setback with the Supreme Court’s junking of the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain. In 2010, Ameril Umbra Kato organized his supporters in the MILF’s 105th Base Command into the BIFF.

We in the government peace panel officially learned of these troubles in our April 2011 meeting. According to the MILF panel chair, Mohagher Iqbal, his group was talking to Kato but the latter “cannot accept endless negotiation and forever ceasefire.” On the other hand, the MILF could not accept two armies under its roof.

Internal reconciliation efforts eventually failed. With the BIFF rejecting the Nur Misuari-led MNLF faction’s offer to align, the next years instead saw Kato’s group working more closely with JI operatives led by Zulkifli bin Hir, alias Marwan.

JI itself tapered off with the killing of Marwan in Mamasapano on Jan. 25, 2015. But both the ASG and the BIFF persisted.

The young ones

Over the years, similar upstart groups came and went, their leaders killed, their followers scuttled.

Although they all started small, some groups became more potent than others. This is true of the so-called Maute group, which was formed in 2012 by Abdullah and Omarkhayam Romato Maute of Lanao del Sur. The brothers called their group Daulat Ul Islamiyah, but they also referred to it as IS Ranao.

I encountered the Maute group in mid-2015. That was when we organized a series of Brigada Eskwela activities in three Butig schools in Lanao del Sur. We dropped the third school site because the MILF was unable to guarantee our safety. Eight months later, that place became the scene of a 10-day fighting when the Maute group occupied the municipal hall.

In these battles, Aziza Romato, the second wife of the late MILF vice chair Alim Abdul Aziz Mimbantas, lost two sons. I met Aziza in one of the meetings of the Task Force Camps Transformation held in the MILF’s headquarters, Camp Darapanan. As a mother, I commiserated with her loss.

The Romato clan owns the land that hosts the MILF’s Camp Bushra. MILF founder Hashim Salamat and Mimbantas were buried in the nearby mountain. With the ascent of the Maute group, parts of these areas are now off-limits to the MILF.

Little is known about Ansar Al Khilafah Philippines (AKP), which operates in South Cotabato and Sarangani. But AKP has been described as having the closest links to IS fighters through their Indonesian and Malaysian comrades.

Period of limbo

No doubt the stalled implementation of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro and the failure of the 16th Congress to pass the Bangsamoro Basic Law prevented the consolidation of whatever the peace process had gained on the ground.

The delay lent credence to the Islamist discourse against supporting the peace process, heightened the historical Muslim distrust on the government, and put the MILF’s credibility at stake.

Misuari’s hands were similarly tied. Holed up in a remote village in Sulu, evading a 2013 warrant of arrest, he hardly offered a viable alternative pole. In fact, he lost hundreds of loyal fighters in the Zamboanga siege, notably the charismatic Habir Malik.

The country, meanwhile, entered the circus of elections and dropped everything to ride out the exercise. In this period of limbo, the new militant groups stealthily moved in and the four major Islamist groups eventually conjoined.

Four-cornered alliance

Looking back, the September 2016 bombing in Davao City was a flashpoint that signaled the four-cornered alliance of Hapilon’s ASG, Maute group, AKP and BIFF was now in action.

There is potency in this alliance, which has enabled the four groups to operate out of their respective rural home bases into urban centers like the cities of Davao and Marawi, and even the nearby seas over to the Visayas, as shown by the pursuit operations conducted in Bohol in April. Together, the four groups represent a unity that transcends tribal affiliations.

Moreover, with the claimed IS mantle as the prospective caliphate in the region, the four groups can provide sanctuary and mobility not only to each other but also to foreign jihadists.

This alliance did not happen overnight. The groups at first operated independently. The International Alert’s Conflict Map separately attributed 463 and 482 deaths to hostilities involving the ASG and the BIFF respectively from 2011 to 2016. The Maute group caught up belatedly, with 83 deaths resulting from AFP-Maute hostilities halfway through 2016.

It may be said that one unintended consequence of the botched AFP-PNP mission to arrest Hapilon on May 22 was to upset the plans of the alliance. Still, the fierce response of the Islamists points to a large arsenal of weapons and a wide network of supporters in the area. ASG-Maute allies in Maguindanao or those in Basilan and Sulu have not even been mobilized.

Keeping the peace

What have held back a full-scale war in Mindanao are the stable ceasefire and the functional security cooperation between the government and the MILF, the biggest organized Moro armed group. The MILF and other MNLF factions have stayed the course of peace. Except for Misuari, all the other MNLF leaders are collaborating on the redrafting of a Bangsamoro Basic Law.

As for Misuari, having secured a safe conduct pass from the new administration, he is held at bay—a safe, smiling distance from the administration of President Duterte.

Similarly, the appointment of three leftist personalities in the Cabinet, the unilateral ceasefires and reopened peace negotiations with the Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army-National Democratic Front of the Philippines (CPP-NPA-NDFP) have staved off simultaneous action on other rebel fronts. Fighting in NPA areas in the eastern and northern regions of Mindanao would have thinly dispersed AFP troops.

Although these overtures from the Duterte administration have not prevented the NPA from launching attacks like the burning of private properties of agribusiness firms and calling on its forces to resist the declaration of martial law in Mindanao, these have stopped the CPP-NPA-NDFP from actually going all-out against the government.

However, all these remain tenuous. What is called for is a more cohesive, nuanced, and comprehensive response to the problems associated with the various sources of armed conflict affecting Mindanao and the rest of the country.

Is the declaration of martial law necessary to address the threat of radical Islamism in the Philippines? What is the way forward? These questions will be addressed in my next article. —CONTRIBUTED