New year, uncertain future

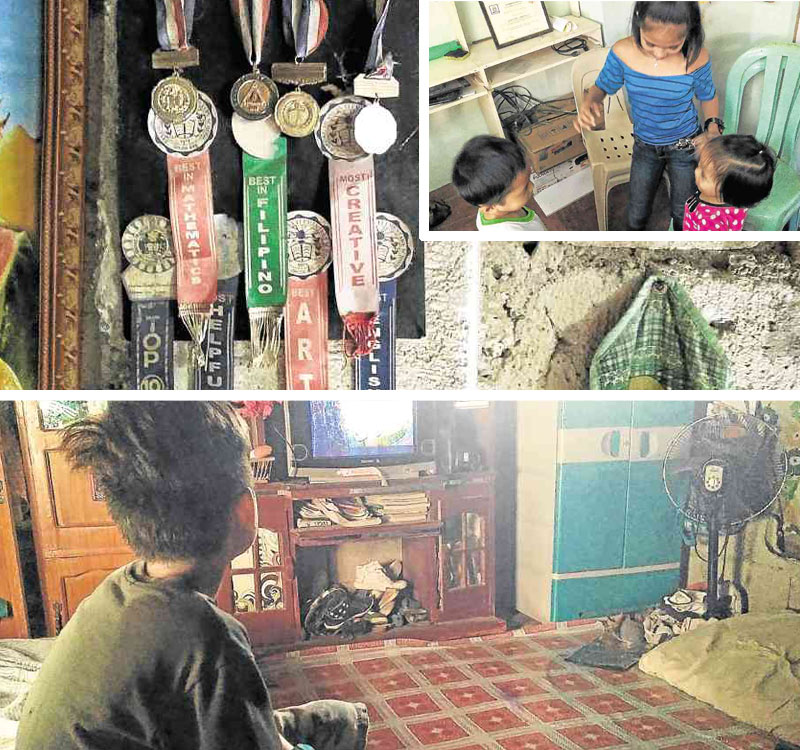

Linda (topmost photo), Alden and Anna are just a few of the children who are trying to get on with their lives after losing their parents to the government’s all-out war on drugs. Another is Jimmy, a bemedalled high school student who has lost interest in his studies after his father, Joseph, was killed in an alleged police operation. With Joseph gone, his wife has been left to fend for herself and their seven children. —PHOTOS BY JHESSET ENANO

While a new year brings a promise of hope, drastic change has come to the families of those killed in the war on drugs. Change—the spark that fueled Mr. Duterte’s popular campaign—has come knocking on the doors of suspected drug users, leaving behind a bloody trail.

Asked how she celebrated Christmases and New Years past, 11-year-old Linda readily answered: “With my family.”

However, the death of her parents—drug suspects who earlier surrendered under “Oplan Tokhang”—has torn her family apart. She and her six siblings now live in different houses, having been adopted separately by their relatives who could not take all of them in.

On the night of Aug. 25, Linda woke up to three masked men kicking open the door to their house in Camarin, Caloocan City. She saw bullets tear through her parents’ heads and bodies. She later held them in her arms as she swore at the gunmen who threatened to kill her if she did not shut up.

Seven gunshot wounds for Papa Albert and eight for Mama Lilia, Linda (all names have been changed to protect the children) recalled as though she was just counting her fingers.

Article continues after this advertisementShe and her siblings are just a fraction of the number of children orphaned by the administration’s bloody war on drugs. In its first six months, over 6,200 deaths have been recorded, both at the hands of policemen and vigilantes.

Article continues after this advertisementPresident Duterte has recently apologized for the “unintended killings” in the drug war which he branded as “collateral damage.” But what has not been given equal attention are the grieving families and loved ones they left behind.

For Linda, this is the second New Year’s Eve without her parents who were once jailed for petty crimes. At one point, the family welcomed the new year in the visiting area of a police station.

“I knew it was going to happen, that they were going to get killed,” said Linda who has been blaming herself for her parents’ death. Maybe if she had warned them, they could have avoided their fate, she reasoned out.

Separate lives

She now lives with her grandmother who also adopted her brother Alden, 8, and sister Anna, 5. Three other siblings aged 10, 4 and 1 are in the care of another relative. The eldest who is 13 years old is with a guardian.

On New Year’s Eve, Linda did not get to see her other siblings as her relatives said that it was unsafe to go to Caloocan City where seven people were killed recently by masked men.

Even her siblings Alden and Anna were elsewhere, visiting other relatives in another area. For Linda, it is now apparent that with her parents’ death, their family will never be complete, even on special occasions.

For Mary, her husband’s death in the hands of policemen began a whirlwind of hardships for her family.

Police reports said that Joseph, 44, was a notorious drug dealer in Barangay Bagong Silangan, Quezon City. They narrated that at 12:30 p.m. on Aug. 7, there was a buy-bust operation in his house in Jubilee New Life. Instead of surrendering, however, he shot at policemen who fired back, killing him.

But his wife, children and neighbors tell a different story: On that day, a big number of policemen had swarmed over the area, dispersing the crowd who had gathered on the road to attend a Bible study. Mary said they were all told to hide inside their houses before four gunshots rang out.

But she didn’t know then that it was her Joseph until she saw his body at the morgue.

Today, her seven children are without a father. The impact of his death showed itself in child’s play. During the interview, 7-year-old Julius, the youngest of the brood, kneeled in front of this reporter and placed his hands on his head.

“That was how their father pleaded for his life,” Mary said before telling this reporter about a huge bullet hole on one of her husband’s fingers. “He did not own a gun. He only had an axe which he used to chop wood.”

Deprived of a second chance

Mary knew that Joseph, a pedicab driver and jeepney dispatcher, used to take illegal drugs so that he could work longer hours. “But he was a changed man. Why did they not give him another chance?”

Steeped in poverty, Mary wants her children to finish their studies. But with her meager income as a housemaid unable to support even their basic needs, they have been forced to stop their schooling.

“After his death, there were days when we ate only once a day,” she said. “But I am not scared anymore as long as nothing happens to my children.”

There are medals and ribbons displayed on the walls of their house, earned by another son, 14-year-old Jimmy. But Mary said her husband’s death had distracted her son from his studies and left him more aloof and quiet.

Still, the family welcomed the New Year together, as Joseph’s ashes remained in the house, next to his photograph.

But the family might be torn apart once more as Mary mulls leaving the country to work overseas. At present, she earns a mere P150 a day. As 2017 starts with Joseph gone, Mary is now left with a burning question: “What will happen to my children when I’m gone?”