September 1972: Recalling the last days and hours of democracy

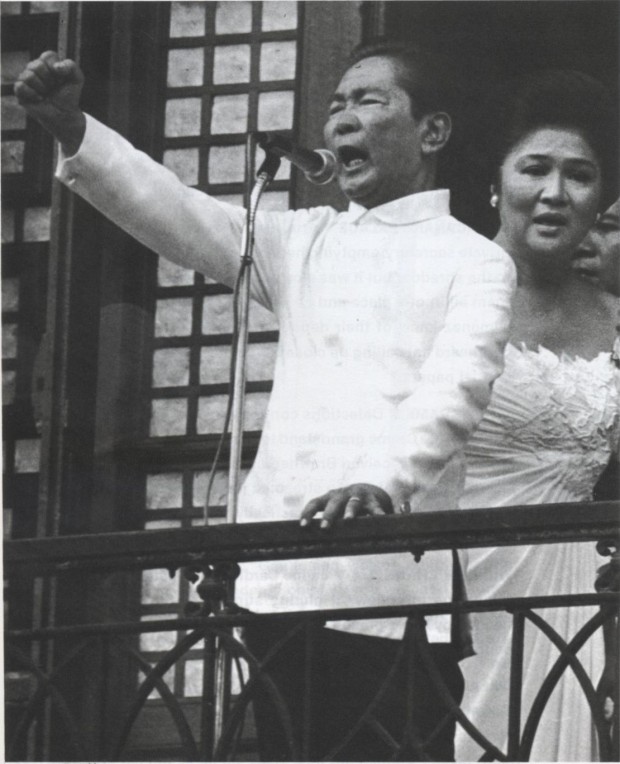

Former dictator Ferdinand Marcos with wife Imelda. FILE PHOTO

Proclamation No. 1081, the document that placed the country under martial law is dated Sept. 21, 1972. The fateful date is divisible by President Ferdinand Marcos’ lucky number 7 in keeping with his known obsession with numerology.

When the proclamation was signed is still subject of debate. There are sources that say it was signed on Sept. 17, Sept. 22or even on Sept. 23.

Below is timeline of events before the announcement of martial law on Sept. 23, 1972 which some insist as the correct anniversary for the declaration of martial law.

March 15 to Sept. 11, 1972. Twenty terrorist bombings occur in Metro Manila. All the bombings, without exception, had been attributed by the military authorities to the “NPA/MAMAO urban guerrillas.”

Among the places the bombings occurred were on in the Palace Theatre on Ronquillo Street, at a department store on Carriedo Street, at the buildings of Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company, entrance of the Board Room of the Filipinas Orient Airways, porch of the South Vietnamese embassy, Philippine Trust Company branch in Cubao, Phil-American Life Building, Senate Publication Division and the Philippine Sugar Institute in Quezon City, and at the SWA building in San Rafael. At least one died in the Carriedo bombing and more than 40 people were injured in the incidents.

Article continues after this advertisementSept. 11. On his birthday, Marcos releases the book, Today’s Revolution: Democracy. The book analyzed what was wrong with the country. It drew a picture of a heroic president trying to create a viable economy despite the hardships posed by the communists, “oligarch families” and elitist politicians.

Article continues after this advertisementThe release of the book was seen as the justification for martial law.

READ: How Marcos planned martial law

– A huge rally is held at Plaza Miranda under the auspices of the Movement for Democratic Philippines where thousands of demonstrators laid the blame for the terroristic bombings “on the Marcos administration.”

– The National Union of Students of the Philippines holds a “Tyrant’s Day” rally in front of Malacañang. A former intelligence officer of the Armed Forces who spoke at the rally pointed out that only one person had been killed in the series of bombings. He said, “That is not the way a terrorist works, as he wants to spread fear by killing as many people as he can.”

Sept. 12. President Marcos says the “rising tide of violence in the land” provides basis for the use of emergency powers.

Sept. 13. In his privilege speech at the Senate, Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., exposes Operation Plan (Oplan) Sagittarius, allegedly Marcos’ master plan to seize power. Under the plan, Greater Manila and the towns of Rizal and the entire Bulacan province would be put under military control as “prelude, maybe, to clamping martial law.”

Aquino scores a “devilish plot” when he noted that the “so-called increased sabotage activities and liquidation plans by urban guerrillas operating in the Greater Manila area is the main cause for the plan.” Yet, the plan was conceived even before the bombings, he says.

THAT’S WHAT FRIENDS ARE FOR Ninoy is shown with fellow members of the Liberal Party Jovito Salonga and Gerry Roxas.

He also notes that one of the two arrested bombing suspects was a PC (Philippine Constabulary now the Philippine National Police) sergeant who was employed at the Firearms and Explosive Section of the PC.

He points out that only one bombing had caused death and injuries to people and that “the bombings had all been timed for maximum publicity and nothing more.”

Sept. 16. Marcos declassifies a confidential report submitted to him by Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, which claims that Aquino had met secretly with communist leader Jose Ma. Sison, indicating a possible linkup between the Communist Party and the Liberal Party–a charge which Aquino denied.

Sept. 19. Bombs explode in Quezon City Hall where the Constitutional Convention was meeting. Despite tight military security, bombers manage to plant dynamite sticks with timing devices. Explosions within seconds of each other occurred in a fourteenth-floor men’s room and a sixth-floor bathroom. Eleven people were hurt.

Sept. 20. Marcos cancels all his appointments and goes into a lengthy meeting with the armed forces top brass, Enrile, Justice Secretary Vicente Abad Santos and Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor.

Sept. 21. Some thirty organizations hold rally at Plaza Miranda to “denounce the pattern of fear and repression pointing to an impending imposition of martial law.”

Sept. 22. Friday Noontime, Marcos meets with US Ambassador Henry Byroade to discuss the need for martial law.

Before 9 p.m. Enrile, on his way home to Makati, is “ambushed” by “communist terrorists” who peppered one of the cars in his convoy with bullets. Enrile escapes unharmed.

READ: True or false: Was 1972 Enrile ambush faked?

He would later admit at a press conference with Fidel Ramos in February 1986 that the ambush had been staged. He and Ramos were part of the “Rolex 12,” the group of military advisers who had helped Marcos plan martial law.

Among the 12 were Gen. Fabian Ver; then Armed Forces Chief of Staff Gen. Romeo Espino; then Army chief Gen. Rafael Zagala; Gen. Ignacio Paz, head of Army intelligence; Air Force Gen. Jose Rancudo; Navy Rear Adm. Hilario Ruiz; Gen. Tomas Diaz, head of a key Constabulary unit; Gen. Alfredo Montoya, head of the Manila Metropolitan Command; Col. Romeo Gatan, commander of the constabulary in Tarlac; and, Eduardo Cojuangco, the only civilian in the group.

But then, in his memoir published in 2012, 40 years after the declaration of martial law, Enrile denied that the ambush had been staged. “This is a lie that has gone around for far too long such that it has acquired acceptance as the truth … This accusation is ridiculous and preposterous,” Enrile said in his book.

9 p.m. President Marcos calls the attack on Enrile “the last straw,” signs Proclamation No. 1081, which puts the entire country under a state of martial law. (As stated earlier, when Proclamation No. 1081 was actually signed is still the subject of debate.)

In accordance with the proclamation, Marcos would rule by decree, general order and letter of instruction, functioning both as President and Congress.

Midnight. First on the list to be arrested is Aquino, who was widely recognized as Marcos’ main political rival. He is arrested at the Hilton Hotel in Manila by members of the military led by Colonel Gatan. Aquino had been discussing tariff matters with colleagues when invited to “step outside” the hotel. Upon returning to the group, he says, “I’m sorry I can’t address the meeting. I’m being arrested.”

READ: Ninoy’s arrest

Sept. 23 (Saturday)

1 a.m. to 4 a.m. Marcos orders his political opponents rounded up, all schools closed and all communications and public utilities placed under government control.

Without warning, the military seize and seal media establishments, walking into their offices and posting announcements that said, “This Building is Closed and Sealed and Placed Under Military Control.” They also order the staffers to leave.

1 a.m. Sen. Jose Diokno is arrested at his residence.

2 a.m. Sen. Soc Rodrigo is arrested.

4 a.m. By dawn, the Camp Crame gymnasium is starting to get crowded with the 100 of the 400 listed subversives already rounded up. The list of detainees included Ramon Mitra and Sergio Osmeña Jr., businessman Eugenio Lopez Jr., teacher Etta Rosales, lawyer Haydee Yorac, journalist Amando Doronila, and other prominent Marcos opponents, outspoken journalists, labor union organizers and delegates to the 1971 Constitutional Convention.

6 a.m. Radios are silent, television sets are blank and newspapers are off the streets as nation wakes. Journalists remember the first months of martial law as among the darkest. Airline flights are suspended indefinitely and overseas telephone operators refuse to accept incoming calls. There is no immediate official announcement, but news about what had happened while the nation was sleeping spreads like wildfire.

Rumors circulate that Senator Aquino’s major crime was his opposition to Marcos, and that declaring martial law was a way for the President to stay in office beyond the constitutional limit of two terms.

(In all, at least eight major English newspapers, 18 vernacular, Spanish and English language dailies, 60 community newspapers, 66 TV channels, 20 radio stations and 292 provincial radio stations were closed down soon after the imposition of martial law.

Mass arrests of journalists and deportation of foreign media men followed. Only newspapers which were mouthpieces of the government were allowed to open. Military censors sat at city desks to monitor stories that might not be positive about Marcos’ New Society.)

3 p.m. A stern-faced Press Secretary Francisco Tatad goes on air over television and radio and in a slow monotone tells the country about Proclamation No. 1081.

7 p.m. Marcos himself goes on air for the formal announcement of the proclamation. He imposes curfew and bans public demonstrations.

Marcos would later close down Congress, taking over the power to make laws. From September 1972 to May 1978 (when the Batasang Pambansa or National Assembly was convened), Marcos was the one-man Congress; all laws came from him alone.

In reality, from 1978 to 1986, Marcos retained his power to make laws such that there was the unusual situation of the Batasang Pambansa and Marcos both having the power to make laws. But it was not that complicated as the Batasan was controlled by Marcos allies (Marcos’ critics called the Batasan his rubber stamp); there was hardly any conflict.

Over 6,700 laws were promulgated by Marcos from September 1972 to February 1986, composed of 2,036 presidential decrees, 1,525 letter of instructions, 61 general orders, 690 executive orders, 1,409 proclamations and other issuances.

Sources: Inquirer Archives, Impossible Dream by Sandra Burton, The Marcos Regime: Rape of the Nation by Filemon C. Rodriguez, Waltzing with a Dictator by Raymond Bonner, A Nation Reborn: Kasaysayan: The Story of the Filipino People, Vol. 9, Philippine Free Press September 23, 1972, A Garrison State and other Speeches: Senator Benigno “Ninoy” S. Aquino, Jr., Six Young Filipino Martyrs edited by Asuncion David Maramba

RELATED VIDEOS