Continuous cycle of malnutrition leads to unfulfilled dreams

Save the Children’s “Reach” campaign highlights the drastic effects of growth stunting among children due to malnutrition. PHOTO BY MEG ADONIS/INQUIRER.net trainee

“We will wait for five more minutes. If Marso doesn’t respond, it means he’s gone.”

These were the most painful words Angelita Salonga, 28, had to hear about her 2-year-old son, whom doctors had diagnosed with pneumonia, dehydration and tumors on both lungs in February this year. Only hours earlier, she had rushed Marso to a hospital on a motorcycle because he had trouble breathing.

On their way, she had placed her head on his chest. She could not feel it rise and fall. She could not feel a proper heartbeat.

Five minutes later, Marso succumbed to his illnesses. Salonga had hoped and dreamt that he would be his family’s “redeemer”—a bright ray of hope to cast light on their difficult life.

“It’s very painful to lose a son. I did everything for him,” she narrated two months later to nongovernment organization (NGO) Save the Children. “We wanted him to finish schooling and have a stable job, unlike how we are now.”

Article continues after this advertisementSalonga’s voice visibly broke at every mention of her son. Behind her, on camera, is her home in Barangay North Bay Boulevard North (NBBN) in Navotas City. The cabinet doors in the kitchen are decorated with flowers and clouds, drawers are adorned with big, yellow stars.

Article continues after this advertisementJust a few meters from their house, trucks loaded with different types of seafood haul these goods into the fish port every morning. Everyday, Salonga had to sift through garbage just so she could earn a living and feed her four children.

But before help could reach them, the Salonga family was not able to reverse Marso’s fate with the little food they could afford from digging through piles and piles of garbage for scraps to sell.

In February 2016, Marso succumbed to the drastic effects of malnutrition, just shy of 3 years old.

Poor children more likely to be malnourished

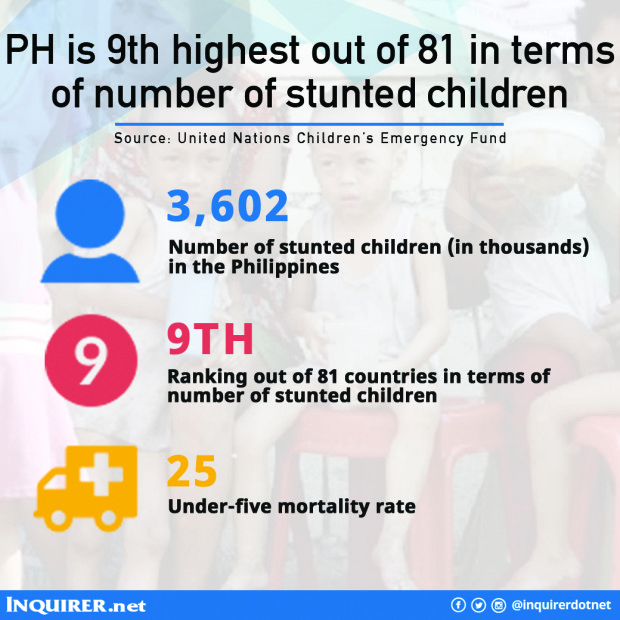

Marso’s death is just one among thousands caused by malnutrition. The Salongas of Navotas, the second to the poorest city in developed Metro Manila, are just one among thousands of families in the Philippines living below the poverty line, thus most vulnerable to diseases brought about by malnutrition.

READ: Stunting worsens despite GDP growth

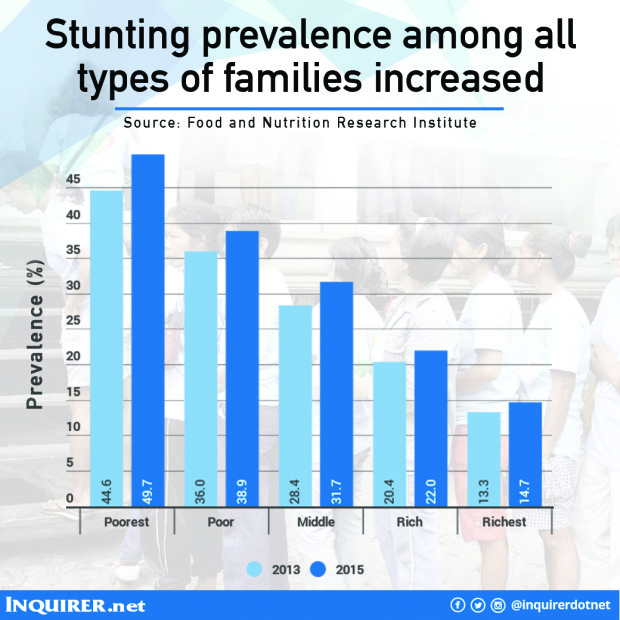

Data from the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) showed that the rate of stunting prevalence among Filipino children under 5 years old rose to 33.4 percent in 2015, up from 30.3 percent in 2013. For children who are both under 5 years old and belong to families under the poverty line, the rate is even higher at 49.7 percent, up from 44.6 percent in 2013.

Lilibeth Dasco, FNRI senior science research specialist, said in an interview with INQUIRER.net that this was because families like Salonga’s did not have the same access to food as compared to those under the richest group of Filipinos.

“If the child has not eaten food in adequate quantities and with sufficient nutrients for long periods of time, then there will be linear growth faltering,” she said. “His height is constrained, and the diseases would always come back.”

With little access to food comes food insecurity, or the lack of enough food to sustain one’s health. When a child is not fed properly, he or she begins a continuous “cycle” that causes further malnutrition and, worse, death.

READ: Editorial: Food for thought

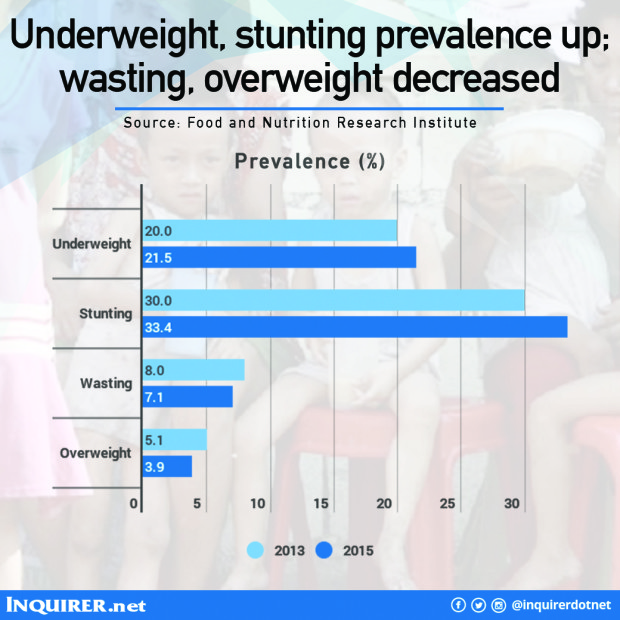

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines stunting as growth retardation or delay, as a result of exposure to prolonged hunger. In the Philippines, all stunting rates spiked in 2015 compared to 2013.

The high rates of stunting due to malnutrition in the country are a far cry from the 20 to 29 percent cut-off recommended by the WHO.

In a 2011 report by the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund, the Philippines ranked 9th out of 81 countries in terms of highest numbers of stunted children. Neighboring countries like Indonesia, Vietnam and Myanmar ranked 5th, 17th and 19th, respectively.

Stunting most prevalent in PH

Malnutrition, however, is not limited to stunting alone. The WHO identified three other kinds of malnutrition mainly underweight, the result of low intake of food; overweight, the result of over-intake of food; and wasting, or having a low weight-for-age. The prevalence rates of both underweight and stunting increased in just two years, while those of wasting and overweight lowered.

Dasco clarified that stunting has more long-term effects while wasting is classified as a “current” problem. She explained that even if children have the right weight and the right height, they might immediately lose weight once they are not properly fed.

Among the four kinds of malnutrition, stunting remains the most pressing in the country because not only do more children suffer from it, but many people are not even aware that it is a problem.

Save the Children health and nutrition adviser Amado Parawan said in an interview with INQUIRER.net that his NGO’s main concern was how Filipinos usually dismiss the problems as a “racial characteristic,” often mistaking shortness in height as genetic.

This assumption must be changed, first and foremost, Parawan said, “The WHO said that the child growth standard is global. A 5-year-old child anywhere around the world will have this particular height if given the optimal care and nutrition,” he said.

Parawan noticed that majority of the Filipinos almost never recognize stunted children as malnourished. “They think malnourished children are only those who are very thin. [They don’t know that] those who are lacking in height are also malnourished. […] They only notice wasted children, but stunting is more serious,” he said.

Preschool years as ‘window of opportunity’

The symptoms of stunting are often not noticeable until the child’s preschool years.

“When they are 3 to 5 years of age, that is when the parent would notice the effect [of stunting] because it’s long-term. It’s not [like wasting] that if you just keep feeding your child, he or she would gain weight the next day,” said Dasco of FNRI.

In 2013, a study by The Lancet medical journal came out about how the child’s first 1,000 days—from conception until two years of age—serve as the “window of opportunity” for the child to be saved from malnourishment.

“If you have intervention programs [during those first 1,000 days], then you will still be able to reverse [the effects of] malnutrition. But if you do it after the child turns 2, it would be difficult,” Dasco said.

Most parents, however, seem to be unaware of the “window of opportunity” and its importance. Moreover, the problem does not lie solely on how the child is treated during his or her early years. Parawan of Save the Children confirmed that child malnutrition could also be a “hereditary” problem, as malnourished mothers, more often that not, bear malnourished children.

“If the mother is malnourished, [then she] has a small uterus; it will not expand because [the mother] lacks uterines. That’s what we call intrauterine growth retardation,” he said. “The fetus will not grow [properly] and when the baby comes out, he or she is already stunted.”

Thus, more children grow up malnourished, and the cycle continues.

READ: Malnutrition threatens 1.5M Filipino children–UN

How to ‘graduate’ from malnutrition

On the part of Save the Children, Parawan asserted that breastfeeding was the primary solution to the growing number of malnourished children. In fact, one of their programs, called Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), includes educating poor mothers, particularly those expecting children in their teenage years.

“If they are teenage mothers, we enroll them in our maternal and child health program… so we can also take care of them. We teach them family planning,” he said.

Under the CMAM program are three concrete steps aimed at helping malnourished children “graduate” from their condition, gradually going from severely malnourished to moderate and to normal.

First, Save the Children does house-to-house visits to assess the children and prevent the growing number of cases in which parents “hide” their children. “Sometimes, the mothers hide their malnourished children because they feel ashamed. [They are afraid] it shows that they do not know how to take care of their children,” Parawan said.

The second step is validation: Check the heights and weights of the children to classify them as normal, moderately malnourished or severely malnourished.

During a validation phase in Barangay NBBN in March 2016, Save the Children identified 117 children as moderately malnourished and three as severely malnourished. (Today, those diagnosed as moderately malnourished are now all normal and those severely malnourished, moderate.)

Lastly, the trained barangay health workers give the parents ready-to-eat supplementary food for their children, such as peanut butter laden with essential vitamins and minerals.

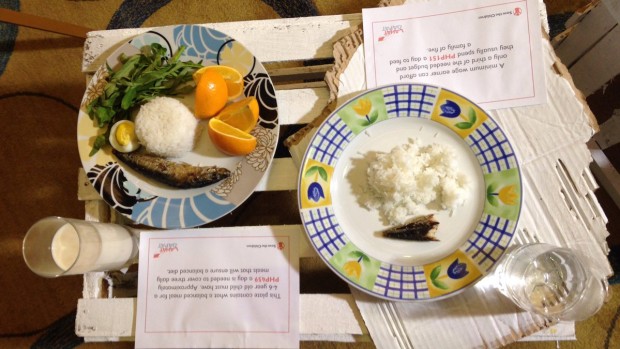

Save the Children showcases the kind of food needed by a child aged 4 to 5 (left) vs what a minimum wage earner can afford. PHOTO BY MEG ADONIS/INQUIRER.net trainee

Before its Navotas leg, Save the Children had implemented their CMAM program in Mindanao in 2008, following the effects of the armed conflict between the military and Moro Islamic Liberation Front rebels, and in the Visayas soon after.

Save the Children also launched last month their “Reach” advertisement, focusing on the causes and effects of malnutrition, particularly stunting. It was to be shown in cinemas nationwide all throughout July, the National Nutrition Month.

April Sumaylo, Save the Children National Media Manager, stressed that child malnutrition in the Philippines has “very little progress.” She hoped that through Reach, they would be able to ensure that no child dies before his or her fifth birthday.

“[T]his campaign is really to call everyone’s attention, raise public awareness on the causes of malnutrition,” Sumaylo said. “We are here to stand for the child’s right to life. We’ve been saying that children are the future, [but] we don’t look into the welfare of our children.”

Need for ‘champions’ in gov’t

During the Reach launch last June 28—two days before the inaugurations of President Rodrigo Duterte and Vice President Leni Robredo—Save the Children reached out to the new administration to prioritize the fight against child malnutrition.

“We’re looking for champions in Congress, the Vice President [and] the President to make sure that the problem of malnutrition will be made known to all,” Parawan said. “If we’re not going to do anything, then the future of our children is wasted.”

According to the 2016 National Expenditure Program of the Department of Budget and Management (DBM), the National Nutrition Council appropriated P217,038,000 of its budget this year to its projects, including the “First 1,000 Days” Intervention Package. P138,124,000 was also appropriated for their “Assistance to Local Nutrition Programs.”

Newly appointed Health Secretary Paulyn Jean Rosell-Ubial also said the Department of Health would prioritize giving quality health services to the “poorest of the poor” Filipinos, and that she would implement mandatory annual checkups and the designation of “patient navigators” to ensure this goal was achieved.

READ: New health chief’s been at it so long

Save the Children health and nutrition adviser Amado Parawan introduces the CMAM program during the “Reach” advertisement launch on June 28, 2016. PHOTO BY MEG ADONIS/INQUIRER.net trainee

For 2017, Parawan urged the DBM to increase the allocation for other health-related services and interventions, instead of simply giving just a generic lump sum for health alone.

The health advisor noted that the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) needs specific conditions that the beneficiaries need to comply with in order for them to benefit from the conditional cash transfer (CCT) scheme.

“There should be conditionality [so the families] do not just accept and accept cash. Perhaps they need to attend breastfeeding sessions, as well as nutrition and livelihood sessions,” he said.

READ: Prioritize fight vs child malnutrition, Duterte urged

President Duterte had said he would continue the CCT program started by his predecessor, former President Benigno Aquino III, but Parawan is hoping the new administration would thoroughly review the 4Ps.

If not, more and more children like Marso could lose their chances to alleviate their families from poverty, and would never have the chance to achieve their dreams.

Sumaylo of Save the Children put it best: “Some kids might want to be future basketball players but they can’t because there’s a height requirement. Imagine if you don’t reach your full height potential.”

That, she added, would and should be unacceptable.