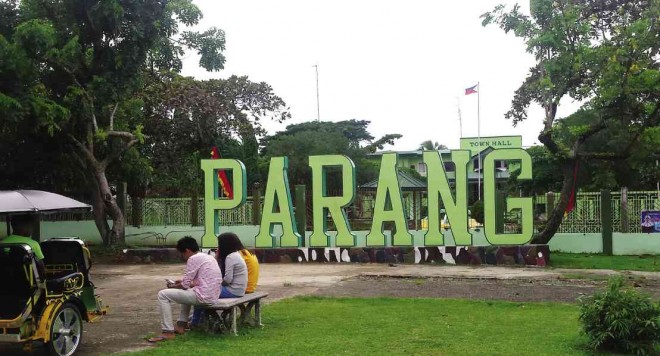

Town torn by war starts to smile

THE TOWN of Parang in Maguindanao province is undergoing a transformation that its people hope would be lasting. It used to be a battlefield for Moro rebels and government soldiers during an all-out war waged by the government and is now trying to bury that past and start anew. MA. CECILIA RODRIGUEZ

There’s one thing common in the different faces that greet tourists visiting the gateway to the Iranun region—their smiles.

Some of the faces are framed in sequined hijabs, some are covered in makeup, some tanned and wrinkled, and some as smooth as porcelain. But the smile is always there, proud to welcome guests to a small town that has so much to offer.

Abdulmaquid Salic, a madrasah teacher, offered an explanation why the people of Parang, a town some 26 kilometers from Cotabato City, were so welcoming to visitors. “Fifteen years ago, in the time of war, the only visitors we had were soldiers, refugees and groups doing fact-finding missions,” he said.

“We knew only fear then, no reason to be happy,” he said. “Conflict was everywhere.”

The so-called Iranun region, which covers the municipalities of Parang, Matanog, Buldon and Barira, had been the hotbed of Moro rebellion since the 1970s. At the inner core of the region is Camp Abubakar, known then as the bastion of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the target of an all-out war launched by the government in 2000.

Article continues after this advertisementOver a million civilians in Maguindanao province were displaced at the height of the war. As the entry point to the embattled region, Parang sheltered hundreds of thousands of internally displaced refugees as villages became battle fields. Government buildings were converted into garrisons, schools into evacuation camps.

Article continues after this advertisementSalic said he had worried that his town would never recover. To help hasten the reconstruction and rehabilitation of Parang after the war, he and his colleagues formed a nongovernment organization (NGO) called Tabang Ako Siyap Ko Bangsa Iranun Saya Ko Kalilintad Ago Kapamagayon Inc., or Tasbikka.

Unique place

Tasbikka sought out volunteers to help build peace and bring prosperity to the Iranun people. Many came forward, most of them having their own grim experience of the war.

“Development is impossible without peace,” said Mohammad Abas, one of the founding members of Tasbikka and who now sits as its interim executive director. “Our first concern was how to put the people back on their feet to rebuild the town,” Abas said.

Having no funds to support full-time employees, Abas and Salic gathered other volunteers to work with the local government to provide livelihood assistance to war victims and former rebels. The group also helped broker the establishment of peace zones in remote villages in Parang and the rest of the Iranun towns.

Mayor Ibrahim “Doc” Ibay said other conflict-torn areas could learn from Parang. “Our town is a unique place in the sense that Muslims and Christians have been living in peace here for over 100 years. About 55 percent of our population is Muslim, the rest are Christians, but we work for peace as one people,” he said.

Abas said that by responding to the basic needs of the people, such as health services, water supply, education, energy and livelihood, they worked for peace themselves and did everything to prevent violence and conflict.

Normalization

When the MILF and the government signed the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro, Parang was among the first towns to celebrate.

“Muslims, non-Muslims, everyone in Parang welcomed the peace agreement. Finally, the war has ended,” Salic said.

But Tasbikka’s volunteers still had more work to be done. A research about the roots of conflict in the Iranun region, which Tasbikka had been part of, identified land-related disputes and the failure to swiftly address boundary issues among families as sources of violence. “Rido,” or clan feud, remains a major concern for Parang and the other Iranun towns as clashes between warring clans become fiercer.

Ibay said the proliferation of loose firearms contributed to the prevalence of violence in the region. “Normalization, which is part of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), will help prevent more violence. But that is not enough. Conflict-resolution mechanisms should be put in place and sustained,” he added.

Apart from normalization, Ibay suggests that customary ways to resolving disputes among families be respected. “We cannot just depend on the traditional justice system, we need to consider customary settlement and alternative dispute mechanisms. Hopefully, under the BBL, these can be strengthened,” Ibay said.

Investment center

With guns silent, people turned to building Parang as a center of economy in the region.

Abas said agri-business opportunities abounded in the region and Tasbikka was helping small farmers take advantage of these opportunities.

“Parang’s land is rich and fertile and its seas are bountiful. As investors are coming in, we are making sure that the people participate in the decision-making. The people should be part of the development process,” he said.

Tasbikka and the local government, with support from various international NGOs, have been working at a master plan for Parang’s comprehensive development along the norms of good governance, environmental protection and inclusive growth.

“We envision to be the investment center of Central Mindanao. We have Polloc Port, one of the biggest ports in Mindanao. We have a bustling trading center and our agricultural lands are still fertile. Parang and its people are off to a bright future,” Ibay said.