In Tagum City, dead get ‘condo units’

THE WELL-PAVED road leading to a giant cross at the center of the sprawling La Filipina Public Cemetery in Tagum City, Davao del Norte province, as seen on Oct. 29. The public burial ground has become a tourist draw due to its “park ambience” and orderly structures. FRINSTON LIM

In Tagum City, the dead have their own “condos.” Neatly arranged rows of tombs and niches for some 20,000 dead in a sprawling 2.5-hectare area have transformed the disorganized, unkempt public cemetery in La Filipina village into a must-see tourist destination in Davao del Norte province.

In contrast to most public burial grounds, La Filipina cemetery is more like a park than a typical “spooky bone yard,” according to Grace Terante, manager of the city economic enterprise office that operates the cemetery.

“You wouldn’t know right away that it’s a cemetery unless you’re inside the premises,” Terante said. “It’s like a park. You wouldn’t be spooked.”

Established in early 2000 during the administration of then Mayor Rey Uy, the cemetery needed to be managed properly with limited spaces for public infrastructure.

For both dead, living

Article continues after this advertisementThe present cemetery is the former bone yard being used in Tagum since the 1970s, with the earliest dead interred there in 1974, Terante said.

Article continues after this advertisementIn 2004, the city government rehabilitated La Filipina cemetery, Tagum’s oldest and biggest, turning it into a place where even the living can use and enjoy.

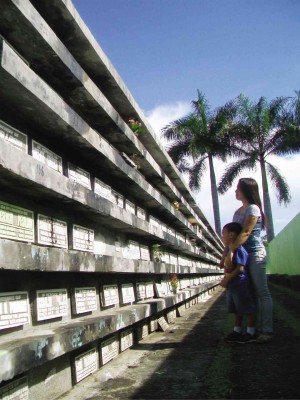

Tombs are built in “apartments” or “condo-type” in up to four rows, with tombs stacked on top of each other. The dead are arranged alphabetically so visiting loved ones can easily locate them.

Separate rows of “condos” were also built as bone niches to maximize land space and make La Filipina usable for up to 20 years.

A total of 2,071 tombs are built in 25 “condo blocks,” while there are at least 10,214 bone niches in La Filipina.

City ordinance

A city ordinance mandated the transfer of the skeletal remains of those in the condo blocks to the bone niches five years after interment, but the transfer period has been extended to 10 years to ensure that only those completely “skeletonized” would be exhumed and transferred.

“We have to ensure the dead are respected,” Terante said.

A WOMAN and her son pray by the grave of a relative in La Filipina Public Cemetery in Tagum City, Davao del Norte, last Oct. 29.

The present public interment area is a far cry from what it was once, she said. The old cemetery was a “typical site of disorganized rows upon rows of tombs of various sizes and conditions, making the place eerily spooky,” she added.

“Before, when you visit the cemetery, you have to walk on the tombs in order to get to your deceased loved one’s grave. In the present setup, there’s a sense of order, so no grave is being stepped on anymore,” Terante said.

Palm trees line each side of the well-paved roads leading to the cemetery, while benches are found in strategic areas. A large cross is at the center of the vast burial ground.

The cemetery is 3 kilometers away from the city proper.

Convenience

Fritzie Sarigumba, a 32-year-old resident of Davao City who visited her father-in-law’s tomb on Wednesday, said La Filipina “is orderly and beautiful.”

“As if this is a park for the living, and not a place for the dead,” Sarigumba said. “Tombs can be easily located.”

To ensure smooth traffic flow, the cemetery management designated only two main entry-and-exit gated points, which are manned by 27 personnel from the city police station, the city’s Security Management Office (SMO) and a few volunteers.

A chapel has been built near the cemetery entrance.

Niches are built in such a way that these are seen as just perimeter walls on the outside, thus maximizing land space.

Enterprise

One component of the city economic enterprise, La Filipina cemetery earns at least P3 million a year from fees.

“We don’t set a target for cemetery revenue because it’s more of a social service. Our collection is used in constructing new tombs and niches,” Terante said.

Each burial costs P3,450 in La Filipina, but families of dead indigents are charged only P1,650 for regulatory fees. The city government writes off the P2,000 allocated for tomb construction.

Due to its ambience, La Filipina has become a favorite haunt, not of the restless souls of the departed but of lovers longing for some uninterrupted hours of trysts.

“The cemetery even became a lovers’ haven,” Terante quipped.

A 9 p.m. curfew was then imposed and 27 personnel from the police, city government and volunteers guarded the 2.5-ha cemetery in three shifts.

Terante acknowledged that it took a lot of political will for past officials to implement the project.

“It was a new idea and people used to oppose it, saying it was a sign of disrespect to their dead. But when they saw the good side of the project, they relented,” she said.

Replicated

Officials under the new mayor, Allan Rellon, enhanced the project, she added.

Since 2005, representatives of about 300 local government units have expressed their desire to replicate La Filipina cemetery after visiting Tagum, officials said.

In Mindanao, areas such as Davao City and Bansalan, in Davao del Sur province, have replicated Tagum’s project. Officials believe this is the right and modern way of honoring the dead.

“For the government, it’s the right way of managing limited public spaces. It’s not really a good sight having traditional cemeteries in every village. For the families of the departed, this means less (funeral) costs,” Terante explained.

She said public cemeteries in the villages of Pagsabangan, Madaum and Busaon would be undergoing a facelift, and eventually be transformed into like La Filipina’s.