Top execs remember martial law

Editor’s Note: Starting Sept. 21, the 42nd anniversary of the proclamation of martial law by President Ferdinand Marcos, we have been running a series of articles to remember one of the darkest chapters in Philippine history. The articles are necessarily commemorations and more so a celebration of and a thanksgiving for the courage of the men and women who endured unspeakable pain and loss to overcome the Marcos dictatorship and regain our freedoms. These are some of their stories.

But every Sept. 21, on the anniversary of the declaration of martial law, EastWest Banking Corp. president and chief executive officer Antonio Moncupa Jr., former Philippine Stock Exchange SVP Jose Fernando T. Alcantara and University of the East (UE) president Ester Garcia are unfailingly taken back to those dark days when they had to muster the courage to rise above their fear for their own safety to pursue a higher goal of helping restore freedom and rule of law in the Philippines.

Moncupa was just 23 when he was arrested together with his mentor Horacio “Boy” Morales on April 21, 1982.

He was Morales’ political aide and was detained for almost two years at the 15th Military Intelligence Group headquarters due to his links to the National Democratic Front (NDF), the political arm of the Communist Party of the Philippines.

Morales, considered one of the highest-ranking members of the NDF at the time, had just picked up Moncupa from his house in Sta. Mesa Heights, Quezon City, when their car was blocked by military agents, who arrested them with drawn guns.

They were taken blindfolded and handcuffed to a military camp in Bago Bantay, Quezon City.

Physical abuse

Moncupa recalls being hit hard by his captors as soon as he arrived at the camp, since the military felt it could not touch as high profile a political detainee as Morales.

So the young Moncupa, who admits to having devoured the writings of Mao Zedong and Marx while completing his economics and accounting studies at De La Salle University, bore the brunt of the psychological and physical torture.

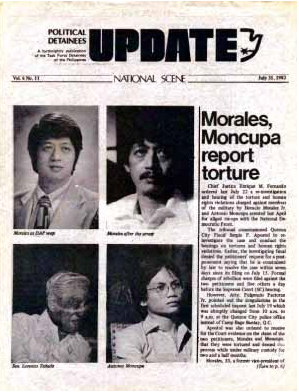

POLITICAL DETAINEES A publication of the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines reports the torture of Horacio Morales (top, right) and Antonio Moncupa Jr. (below, right) in July 1982.

He was not allowed to sleep and was subjected to endless questioning and when he refused to admit his ties to the underground movement, he was subjected to electrocution, beatings and water torture.

Moncupa was eventually released on Jan. 26, 1984, and after lying low for a while, he rejoined the mainstream and made up for lost time.

He finished his degree and managed to go up the ranks of the corporate ladder at a furious pace.

The discipline and the determination that he always had, and enhanced during his years in detention, proved to be valuable ingredients in his success, allowing him to outwork and outwit his colleagues until he became president and CEO of EastWest Banking Corp.

Mental torture

Alcantara was subjected to mental torture during his detention, which lasted for 22 months at Camps Crame and Bicutan.

He said those months passed at a glacial pace, with months spent in solitary confinement, with him trying to recall his prayers in Latin and endlessly reading Mills and Boon romantic novels, as he was barred from reading the Bible or the Koran because of “potentially mutinous content.”

Alcantara was a victim of the military prohibition of any form of assembly and association. He defied the ban and got heavily involved in the formation and organization of two nationwide mass organizations—the National League of Filipino Students, or NLFS (now the League of Filipino Students or LFS), and Samahan ng mga Maralitang Tagalunsod (now defunct).

“These involvements led to my arrest under what was called the arrest search and seizure order (Asso). I spent about eight months hiding in different places before the Military Intelligence and Security Group, or MISG, caught up with me in late 1978,” said Alcantara, whose political science studies at the University of the Philippines fell by the wayside as he concentrated his efforts on the underground movement.

He was released in early 1980. But instead of lying low, the UP Student Council chair of 1981 continued where he left off, even traveling to Baghdad, Iraq, to attend an international conference.

HE’S NOW A BANKER Today, Antonio Moncupa Jr. is the president and chief executive officer of EastWest Banking Corp.

Just weeks after his return to Manila, he was again served an Asso, arrested and detained for another nine months.

‘Annak ti Batac’

Among his fellow detainees were Satur Ocampo, Ed de la Torre and Fidel Agcaoili.

Alcantara, who was just 17 when he got involved in community organizing, told the Inquirer that he was not subjected to physical abuse because he was an “annak ti Batac,” or a native of Batac, the hometown of the Marcos family.

“And because my two separate arrests were monitored by the media, Col. Rolly Abadilla, the head of MISG then, was mindful of my rights. Col. Ka Bise, however, would separate me from the rest and put me in a 1.5-meter-by-2.1-meter, unlit cell. In the middle of the night, he would visit me and subject me to his almost ritualistic barking of “What’s wrong with you, kid. You’re such a shame.”

Alcantara was eventually released with the intervention of his family and local and international nongovernment organizations, and he used his freedom to pursue his studies.

He graduated from UP with a degree in political science and went on to work for a master’s degree in business economics at the University of South Carolina, which he got in 1987, and a Ph.D. in business development economics at the London School of Economics, which he acquired in 1991.

UE president and former Commission on Higher Education Chair Ester Garcia was already an assistant professor when she joined Samahan ng Makabayang Siyentipiko and Samahan ng mga Guro sa Pamantasan.

For being involved in those organizations, she was jailed twice: From Jan. 6 to May 20, 1973, and from Jan. 12, 1976, to Jan. 28, 1977, during which she suffered “mental anguish and anxiety.”

She was arrested for the first time on her way to visit her then boyfriend Jerrold and his friends in their apartment.

Her boyfriend was arrested the day before and the soldiers were waiting at the apartment for associates like her.

She was taken blindfolded to the Intelligence Service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines headquarters in Camp Aguinaldo and was subjected to intense interrogation, although the military held off on physical torture because she came from the powerful Albano political family.

The second time, she and Jerrold, who was by then her husband, were arrested in their home in Novaliches, Quezon City.

They were placed in separate vehicles and taken blindfolded to a so-called safe house by a team headed by Arsenio Esguerra.

“The first time around, I was bodily searched and roughly manhandled during the arrest. Later, they interrogated me, day and night. I was not allowed any visitors for some time,” Garcia said.

“The second time was worse. Every so often, during interrogation, they would point a gun at me, threatening me while shouting insults and curses. The ones who interrogated me the second time around were reputed sadistic officers,” she said.

When she was released, she decided to contribute to the movement by concentrating on her original mission, which was science and engineering and faculty development, a mission she continues to work on today as president of UE.

Garcia does not look back with regret on those years she was an activist, despite the horror of detention.

Many lessons learned

“I learned many lessons during my years as an activist and during incarceration, especially of people skills that have been useful to me while in academic administration, both public and private, and in government service. If I have any regrets at all it would be because during my incarceration, my thesis students had to transfer to other advisers and some of my research projects had to be abandoned. But I consider that as part of my sacrifice,” she said.

She shares those belief and valuable lessons with her students, she said. She takes the time to remind freshmen during orientation and graduates during baccalaureate rites of their duties to do good for their country.

“I often call my baccalaureate rites speech as my last lecture to them,” she said. “I tell them that they are the youth and the future. We had our mistakes and we had our time. The future is now theirs.”

Alcantara said he would like to believe he had remained a “revolutionary” even if he had spent more than 20 years in the corporate world.

“Being revolutionary is not simply about negating, it is about constant eagerness to create better values and conditions,” said Alcantara, executive director of the Chamber of Commerce of the Philippine Islands.

“To my mind, as well discoursed in ‘Das Kapital’ of Marx, human capital is always the heart and connector of business ingredients—people, tools, systems, raw materials and money—to create more value and progress. These are the same core ingredients needed in negating or transforming a situation.”

Never again

Moncupa said Sept. 21 always made him say to himself, “Never again! Never again should we allow one person to rule with impunity and drag the nation down.”

“It reminds me of the human capacity for extremes. How humans can be oppressive and rapacious on the one hand and how we can be heroic on the other. Just to be clear, the Marcos dictatorship was certainly not the heroic one,” he said.

“It also reminds me of Marcos and how important good governance and competent and honest leadership are. The Marcos regime presided over the decline of the Philippines from being one of the more progressive countries in Asia in the mid-1960s to one of the laggards by the time he was done with us,” he said.

Not only Marcos

Alcantara stressed that martial law involved more than just the name Marcos.

“There are so many other names who aided and benefited during those years, and in fact have long returned to politics, to business, to the religious sectors, to the academe. Their return can perhaps be blamed on amnesia,” he said. “Memories and experiences of martial law abuses must remain an undying reminder to protect ourselves from political figures and authorities who may later turn out to be abusive, vicious and corrupt.”

RELATED STORIES

The travails of martial law victims