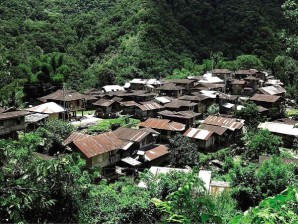

Martial law leaves scar on Kalinga community

LIGLIG is a subvillage of Barangay Tanglag, Lubuagan town, in Kalinga, whose residents share memories of atrocities during martial law. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

LUBUAGAN, Kalinga—William Nagoy was a 17-year-old high school student whom government soldiers tried to arrest in 1976 while he tended a garden for a practical arts class at St. Theresita’s School in Tabuk City.

Now 54, Nagoy said he was one of the teenagers accused of attacking the military in Barangay Tanglag here at the height of the community protest against the construction of the Chico River Dam during the regime of the dead dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

They protested the dam project for fear it would submerge farms and communities.

Nagoy eluded arrest. But those who remained in Sitio Liglig in Barangay Tanglag took the brunt of the excesses of martial law.

“The military tortured and abused residents here who were suspected of protesting the dam project,” Nagoy told the Inquirer last week.

Article continues after this advertisementSitio Liglig is a farming village that can be reached by a two-hour hike across rugged terrain and crisscrossing rivers.

Article continues after this advertisementHuman rights activists had visited the village to listen to its residents’ rich tales about their struggles and sacrifices under the dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s.

They said many of the residents would qualify for indemnification under Republic Act No. 10368 (the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013), which President Aquino signed into law on Feb. 25.

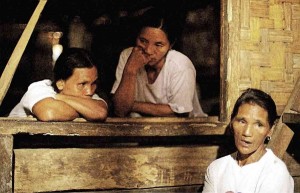

THESE women of Sitio Liglig in Kalinga have stories about atrocities that took place in their small community during martial law. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

One of those arrested for protesting the dam project was Cresencio Ngayaan, 65. He related in Ilocano: “We were made to squat on chairs and we were made to stay in that position. We would be beaten the moment we tried to stand up when the strain of crouching atop the chairs began to overwhelm us. One of the detained men was made to sit on the table. A soldier kicked him so hard he was hurled toward the wall.”

In 1976, Ngayaan said, more than 100 villagers were detained in Camp Olivas in Pampanga for opposing the project.

The stories of Ngayaan and Nagoy are now in affidavits which may be used to secure recognition for them as martial law victims.

Joanna Cariño, a Baguio-based Ibaloi activist, said human rights violations took place in the Cordillera under the Marcos regime but most victims were unable to join the class suit filed in 1993 in a Hawaii court against the Marcos family.

She said she hoped the victims from Liglig would document their sufferings so they would be included on the list of people who would be recognized and indemnified under RA 10368.

Under this law, it would be state policy “to recognize the heroism and sacrifices of all Filipinos who were victims of summary execution, torture, enforced or involuntary disappearance and other gross human rights violations committed during the Marcos regime from Sept. 21, 1972, to Feb. 25, 1986, and restore the victims’ honor and dignity.”

The state would “acknowledge its moral and legal obligation to recognize and/or provide reparation to said victims and/or their families for the deaths, injuries, sufferings, deprivations and damages they suffered under the Marcos regime,” according to the law.

Cariño said local activists also launched a book project to collect stories of villagers and activists in the Cordillera.

Kathleen Okubo, community paper editor and an activist in the 1970s, said: “Every time we meet old friends, the stories are randomly told … how we were detained, how we were arrested in different places. It would be such a waste if these were only told in kwentuhan (verbal sharing). We want to gather and write the stories the way [the events] happened. This is an effort to document the cases and also to renew and reconnect with contacts [so we can] follow these up.”

In 2011, only 10 Cordillera activists, including Cariño, were able to claim reparation from the Commission on Human Rights. Each of them received $1,000 in compensation. They were among the 7,526 victims who won a claims suit filed in a Colorado court against the Marcos family.