When mountain travel is fun yet risky

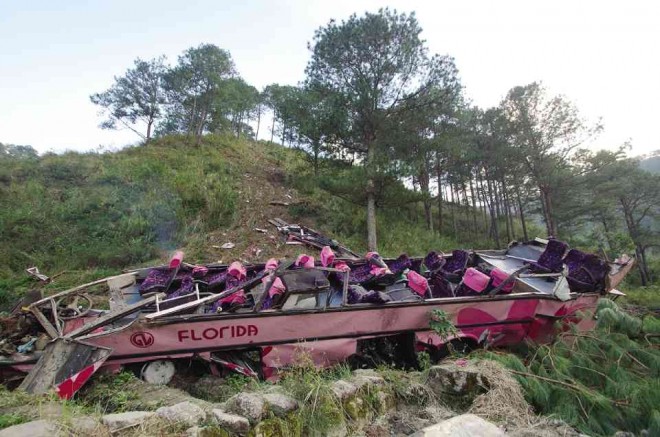

THE WRECKAGE of the Florida Transport bus is left at a farm in Barangay (village) Talubin in Bontoc, Mt. Province. Strewn around it are personal belongings of its passengers, 14 of whom had died and 32 others taken to hospitals in Mt. Province, Baguio City and Metro Manila. RICHARD BALONGLONG

Ain’t no mountain high enough to look at, and that’s how many Filipinos value mountain travel.

The Department of Tourism (DOT) and most upland local governments have spent public funds on road view decks which overlook a lush vista that touches the souls of visitors as they drive up the zigzag roads of the mountain region.

The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) has also improved the condition of 1,931.205 kilometers of mountain roads, heeding the lessons from road devastation wrought by extreme weather since Typhoon “Pepeng” and Tropical Storm “Ondoy” struck in 2009.

Many zigzag roads built in the early 20th century have been paved, and fitted with canals to discharge runoff rainwater flowing down the mountainsides.

And yet, in 2010, the DPWH recorded 227 accidents as it tried to map out “black spots” or accident-prone sections of mountain roads. In 2011, it said 323 accidents took place on upland roads. In 2012, 418 accidents were recorded.

Article continues after this advertisementThe information technology unit of the Cordillera police also analyzed data collected by their Geographic Information System, and recorded 1,581 road accidents in 2012, and 1,201 accidents as of June 2013.

Article continues after this advertisementHuman error

The DPWH said human error caused many of these accidents.

The first week of February saw two accidents happening in the Cordillera. On Feb. 7, a Florida bus from Manila fell into a ravine in Mt. Province, killing 14 people. Two days later, in the town of Licuan-Baay in Abra province, a jeepney overloaded with passengers fell into a ditch, killing five.

The accidents provide some insights into mountain travel for Cordillera folk, particularly those who commute home on weekends.

For example, a resident of Sabangan town in Mt. Province said many upland folk appreciate the Manila-Bontoc (the Mt. Province capital town) route offered by the GV Florida Transport Inc., which owns the bus that fell last week.

The usual route to the upland provinces is to travel to Baguio City for seven hours, and then take another bus to Benguet, Mt. Province or Ifugao via Halsema Highway. A trip to Bontoc from Baguio takes about six hours.

Via top load

In the Abra accident, the ill-fated jeepney was ferrying people in the typical Cordillera fashion: Via “top load,” which is literally riding on the roof of buses or jeepneys.

In 2012, the Department of Transportation and Communications declared that this manner of travel was risky and illegal (officially, the top-loaded vehicles violate the overloading rule).

But top-loading continues because few public utility vehicles ply the long mountain stretches. Tourists, especially those from Europe, enjoy the view offered by hanging onto the roof.

Not for everyone

Mountain travel is a lifestyle that the DOT has marketed since ecotourism became a profitable venture.

But mountain driving is not for everyone. Ifugao Rep. Teodoro Baguilat Jr. said motoring uphill through zigzag roads “requires unique skills and hardy, well-maintained vehicles.”

Unlike highway traffic in the lowlands, the climb requires “defensive driving,” which, he said, some motorists take for granted. This means driving up at low gear to regulate a vehicle’s speed.

Most travelers fail to consider major factors about mountain roads, said Dindo Umandam, 43, a native of Sagada town in Mt. Province, who drives a van or a motorcycle to Baguio via Halsema Highway each week to teach math and science to high school students.

Fog, slippery roads

Fog occasionally envelopes mountain roads. The roads are frequently wet, due to underground channels that discharge water down the slopes.

Drivers, who are not used to slippery roads, often miscalculate when they negotiate sharp curves, he said. “The drivers’ number one enemy is the drizzle. We prefer strong rain to the drizzle. A drizzle or moderate rain could make the road very slippery,” he said. With a report from Gobleth Moulic