Aquino Museum redesign tells saga of democracy

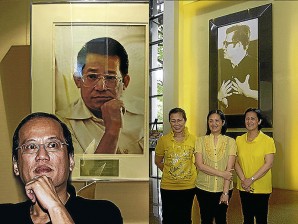

REAWAKENING DEMOCRACY is the theme of the Aquino Museum redesign competition which held its awarding rites early this month at Hacienda Luisita in Tarlac with 3 of the 5 children of Ninoy and Cory—Pinky, Viel and Ballsy—in attendance. At left, President Benigno Aquino III is juxtaposed with the last photo of his father (on exhibit at the Aquino Museum) taken minutes before he was killed at the Manila airport. ARNOLD ALMACEN

TARLAC CITY—“Remember Ninoy!” was the battle cry 28 years ago when the assassination of former Senator Benigno Aquino Jr. triggered a tidal wave of outrage.

And for those who lived through the martial law years, there was no forgetting. Ninoy’s bloodied shirt, the blown-up photograph of him sprawled on the tarmac of the then Manila International Airport, and the replica of his prison cell—the centerpieces of the Aquino Museum in Tarlac City—are more than sufficient reminders of that dark era.

There was no forgetting either for those who witnessed how his widow, Corazon “Cory” Aquino, survived the ordeal to become the Philippines’ first woman president. The outpouring of affection from a grateful nation when she was laid to rest in 2009 speaks volumes of her place in history.

But how does one tell the story of Ninoy and Cory to a new generation of Filipinos? How does one make them feel his loneliness in solitary confinement, the grief of millions over a fallen hero, and the pain and suffering of a people fighting for freedom from a dictatorship?

Reawakening democracy

Article continues after this advertisement“With the new design, they will,” says architect Anthony Nazareno, lead architect of Nazareno + Guerrero Design Consultancy, the top winner in the Aquino Museum redesign competition launched by the Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation and LaFarge Cement Services.

Article continues after this advertisement(The second winner is Mana Architecture + Interior Design led by principal architect Jose Carlos Mateo, and the third, Palafox Associates led by chief architect Felino Palafox Jr.)

The new design will feature a multimedia platform and will cut across generations, according to Nazareno.

LaFarge director Renato Sunico says the competition was conceived in light of the public sorrow and respect displayed during Cory’s wake and funeral in August 2009.

Built in 2001, the Aquino Museum focused more on Ninoy, Sunico notes. But this time, he says, it will also showcase not only Cory’s achievements as president but “the breadth and scope” of her life as “a global icon of democracy, a hero and moral compass to the Filipino people” as well.

Ninoy and Cory’s eldest daughter, Maria Elena “Ballsy” Aquino-Cruz, found the competition enriching because it elicited new ideas and concepts.

“There is something unique and different in each of the proposals,” she says.

Anchored on the theme “Reawakening Democracy,” the competition drew 15 contenders who proposed design solutions that “best capture and translate the full impact of Ninoy and Cory Aquino on Philippine history.”

The best three were selected and their proponents given stipends for research and development of their concepts.

Political timelines

As it is now, the museum exhibit runs in chronology marked by four political timelines interwoven by episodes in Ninoy and Cory’s personal lives.

These are: 1950-1971, Benigno S. Aquino Jr., Pre-Martial Law Years; 1972-1982, Martial Law Years; 1983-1986, People Power; and 1986-1992, Corazon C. Aquino, President of the Republic of the Philippines.

The design and concept were a product of the collaborative work of Dan Lichauco and Joel Enriquez.

The museum’s centerpieces are still Ninoy’s shirt stained with blood (tangible proof of his martyrdom), and the replica of his prison cell (a physical manifestation of his travails).

Those 20 years old and younger would view Ninoy as the closest to a hero. What would perhaps move them is the emotion evoked by the audiovisual presentation shown to visitors as part of the museum run.

Ninoy’s stuff during his detention are seen inside the replica of his prison cell—a white coffee mug adorned with blades of wheat and grains, his green Torpedo typewriter, rubber slippers dented by his weight, books, stainless steel pans and plastic pails.

Outside the cell, hanging on the walls, are verses excerpted from Ninoy’s poem, “Solitary Confinement,” and framed in wood.

The poem written on April 22, 1973, breathes life into the replica and transports the viewer almost 40 years back into Ninoy’s “living tomb,” his own description of the cell where “even saints are forced to cry because angels grow horns.”

The nationalist fervor stops at the People Power episode of the exhibit, marked by the famous photograph of Candidate Cory with arms outstretched amid the multitudes that listened to her call for civil disobedience.

The exhibit is capped by a desert that seems incongruent to what it originally wanted to evoke. The emotional high is lost as one exits.

What follows is a showroom of Cory’s memorabilia as president, dominated by expensive gifts from other heads of state, embassies and members of royalty.

One of a kind

Expected to be completed in 10 months to a year, the redesigned Aquino Museum will be one of a kind, Nazareno says.

There will be more focus on the individual achievements of Ninoy and Cory, and the time zones will be divided into 10 salas (or halls) set in a continuum.

The museum will be presented in narrative form. There will only be one entrance and one exit, so that a visitor has to complete each sala before moving on to the next.

Multimedia will be used, evoking the atmosphere of each period without the visitor having to watch a documentary at the audiovisual room.

For example, Sala 5 is labeled “Hindi Ka Nag-iisa” (You Are Not Alone). It represents Ninoy’s assassination, which was the catalyst of the 1986 People Power Revolution, and is highlighted by a simple memorial with his bloodstained shirt.

Sala 7 is the “People Power Hall.” Says Nazareno: “Rather than a space representing a mere sense of celebration, we wanted to create a sala where people could reflect on the journey of the people’s struggle for regaining democracy, culminating in People Power.”

Sala 9 is called “Citizen Cory,” representing her importance and influence in modern Philippine politics and culture beyond her presidency.

The hall labeled “The Meaning of Democracy” is the final sala. Here, Nazareno says, questions are posed to visitors: Who is Ninoy to you? Who is Cory to you? What is democracy to you?

“It hopes to make museum-goers internalize the many sacrifices endured and to reawaken their zeal in the seemingly simple concept called democracy,” he says.

Nazareno says that if comparisons are to be made, the closest that the new design can be compared to is that of the museum dedicated to assassinated US President John F. Kennedy.

‘Rejuvenating experience’

How he and his team put the new design together was a “rejuvenating experience,” Nazareno says.

He was barely 5 years old when Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in September 1972. His family led a rather comfortable life; they migrated to California but came back more than a year later.

“I had a chance to watch ‘The Last Journey of Ninoy’ when I first visited the Aquino Center in Tarlac,” Nazareno recalls.

“My family supported the Marcoses in the snap election of 1986, and I barely knew who Ninoy was then. That movie changed my perspective on many things. I had not realized, until then, the extent of the sacrifices Ninoy, Cory and their family had to endure,” he says.

“The short but powerful experience” of reliving Ninoy’s life and times through the movie made Nazareno realize that the best way to convey the message to museum-goers was an “experiential approach.”

“With our design, our team hopes to evoke as much of the emotions that [Ninoy and Cory’s] lives elicited in the course of the unfolding of Philippine history in the past 40 years,” he says.