Protecting Masungi: Conflicting views turn area into battleground

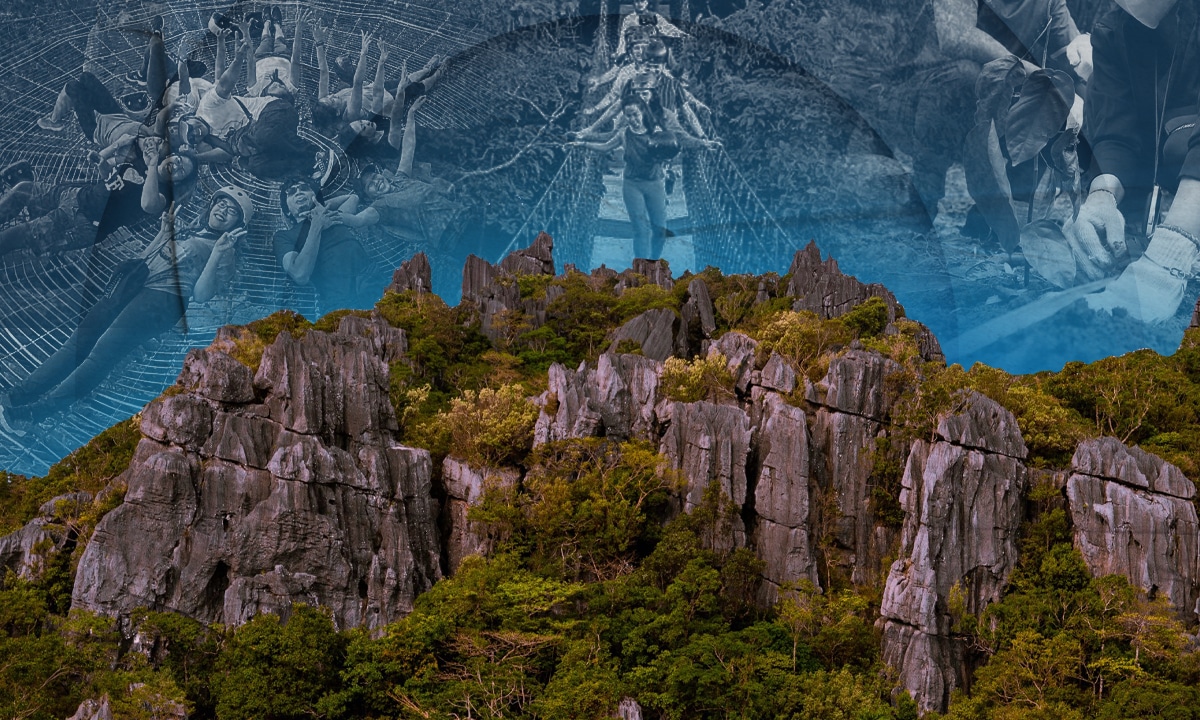

MASUNGI composite image from Inquirer, contributed file photos

MANILA, Philippines—No walk in the park.

This was how a nonprofit organization described its role as steward of Masungi Georeserve, a protected area in the province of Rizal, which had drawn the attention of environmental advocates, including Hollywood star Leonardo DiCaprio.

READ: DENR thanks Leo DiCaprio but says law must prevail on Masungi

The Masungi Georeserve Foundation Inc. (MGFI), which has an agreement with the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to manage the protected area, said its efforts to guard against poachers included generating income from activities that would not harm Masungi.

The income derived from these activities, the MGFI said, is “plowed back to the furtherance of our mission.”

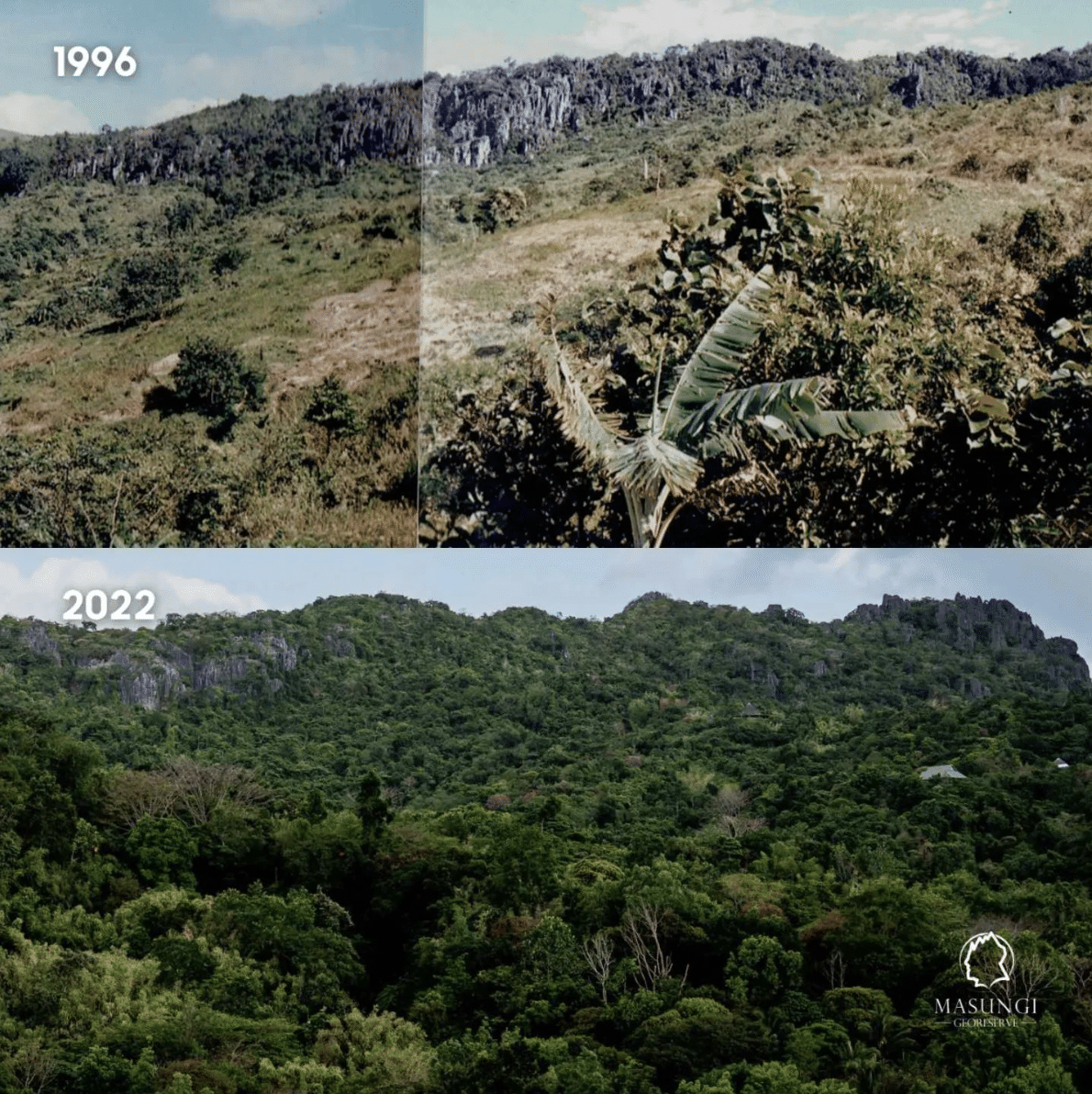

While MGFI was established only in 2016, the conservation of Masungi, in Baras town, Rizal started in 1996, when the reserve was nothing but land scarred by deforestation and neglect: Over the course of 25 years, the barren landscapes are now thriving as secondary forests.

So in 2017, the MGFI signed an agreement with the DENR, then headed by the late Gina Lopez, who asked the group to help preserve the Upper Marikina River Basin Protected Landscape (UMRBPL).

The UMRBPL has a land area of 26,124 hectares, but the agreement, which gave way to the Masungi Geopark Project (MGP), covered only 2,700 hectares of “degraded land” in Antipolo City, Baras, Tanay, Rodriguez, and San Mateo, all in the province of Rizal.

“Before the project started, the site, which was just grasslands and a few remaining pine trees, was being burned yearly,” said MGFI director for advocacy Billie Dumaliang, pointing out that this was evident at the bottom part of the pines. “They were black,” she told INQUIRER.net.

READ: House urged to probe into encroachments in Masungi Georeserve

“Now, baby pine trees are germinating and growing,” she stressed, saying that because of MGFI’s care and protection, the conditions [that let] nature thrive has returned. “You will find the narra trees we planted years ago, which are now more than five feet in height, lining the trails and the mountain tops.”

THRIVING. A comparative photo of how the Masungi Geopark Project looked like in 1996 and 2022. PHOTO COURTESY OF MASUNGI GEORESERVE

As pointed out by the MGFI, through the MGP, 2,000 hectares of forest land have been reclaimed, extensive monitoring stations and trails established, and 100 local rangers, including former illegal loggers, women, youth, and indigenous people, engaged in active conservation efforts.

Dumaliang said that “in several more years, if we succeed, this will be a new forest of narra and native fruiting trees, like bignay, with more than 80 percent forest cover,” stressing how the area looked like when they took over in 2017—a grass and bamboo land, which she said is an indication of severe degradation.

DENR: Deal was ‘void ab initio’

But the DENR, which is now working on the cancellation of the 2017 Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the MGFI and the government, said that “no one is exempt from the law,” with Environment Secretary Toni Yulo-Loyzaga saying that the deal was “void from the beginning.”

READ: Masungi Georeserve denies DENR claim its contract is ‘void ab initio’

“The legal grounds for the [recommendation of] cancellation are what we are calling [void] ab initio (void from the beginning), given the advice of the DOJ (Department of Justice),” Loyzaga told the Senate in April, which was then investigating illegal structures within the Chocolate Hills in Bohol.

As the DOJ previously pointed out, the provision in the contract that gave the MGFI “perpetual land trust for conservation” violated Section 2, Article XII of the 1987 Constitution, which provided that such agreements may be for a period not exceeding 25 years, renewable for not more than 25 years.

[…] The exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources shall be under the full control and supervision of the State. The State may directly undertake such activities, or it may enter into co-production, joint venture, or production-sharing agreements […] Such agreements may be for a period not exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for not more than twenty-five years, and under such terms and conditions as may be provided by law.

But as the MGFI explained, there is a difference between “exploration, development, and utilization” and “conservation,” saying that “strictly speaking, the objectives of conservation activities will not allow exploration, development or utilization of natural resources.

READ: Caritas backs Masungi caretakers: ‘Unwise’ for DENR to let them go

“This is why MGFI forwards that the 2017 MOA should be read as an agreement for a perpetual land trust for conservation, and not a perpetual license,” MGFI said. “We can only manage the project for as long as the law or Constitution allows, which is yet to be determined by the courts for conservation.”

Self-financed

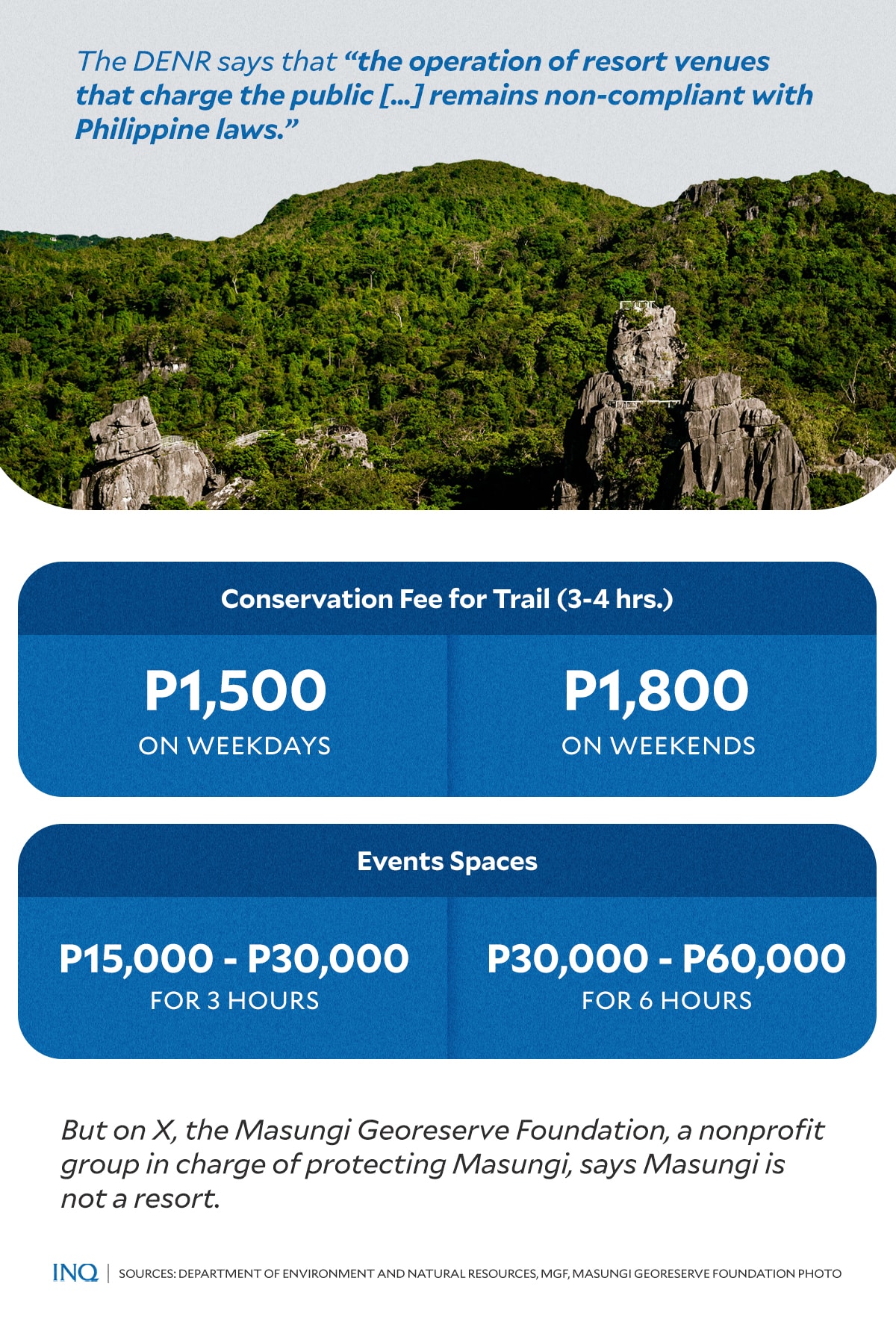

However, the DENR stressed that “the Filipino people own the area occupied by Masungi Georeserve Foundation [Inc.] and the operation of the resort venues that charge the public for day tours, meetings, and weddings remains non-compliant with Philippine laws.”

Back in April, the DENR said that the MGP is a resort and collects entrance fees from visitors-P1,500 and P1,800 on weekdays and weekends.

The DENR alleged that there are accommodations worth P5,000 a night and which provide venues for weddings and company events, with rates starting from P120,000.

GRAPHIC by Ed Lustan/INQUIRER.net

In response, MGFI asked Loyzaga to prove her allegations and if she could not, “she should tender her resignation”: “We dare the DENR secretary to come […] to show to the public where the alleged hotel, swimming pool, and resort are in Masungi Georeserve.”

READ: After Leonardo DiCaprio, more celebrities rally for Masungi

Based on a statement previously released by the DENR, the 2017 agreement between MGFI and the government covers an area of 300 hectares, “which MGFI started operating in 2015 as an ecotourism park for public use.” But as the MGFI said, the park is not a resort and that the alleged hotel or pool is non-existent.

Dumaliang told INQUIRER.net that MGFI is a registered non-stock, non-profit organization, and as defined, “all conservation fees or income goes to the furtherance of the organization’s environmental and social purpose, and none accrue to its employees or trustees.”

READ: Masungi: Watershed protecting NCR under attack with impunity

As stated in its website, MGFI is charging each visitor P1,500 (weekdays) to P1,800 (weekends) in conservation fees. Venues for weddings and company events are worth P15,000 to P30,000 (3 hours) and P30,000 to P60,000 (6 hours).

However, it pointed out “conservation fees for trails and sustainable events make a real impact, from providing meaningful livelihood to rangers, powering reforestation in watersheds, maintaining and improving the trails, and increasing legal protections for the park and its defenders.”

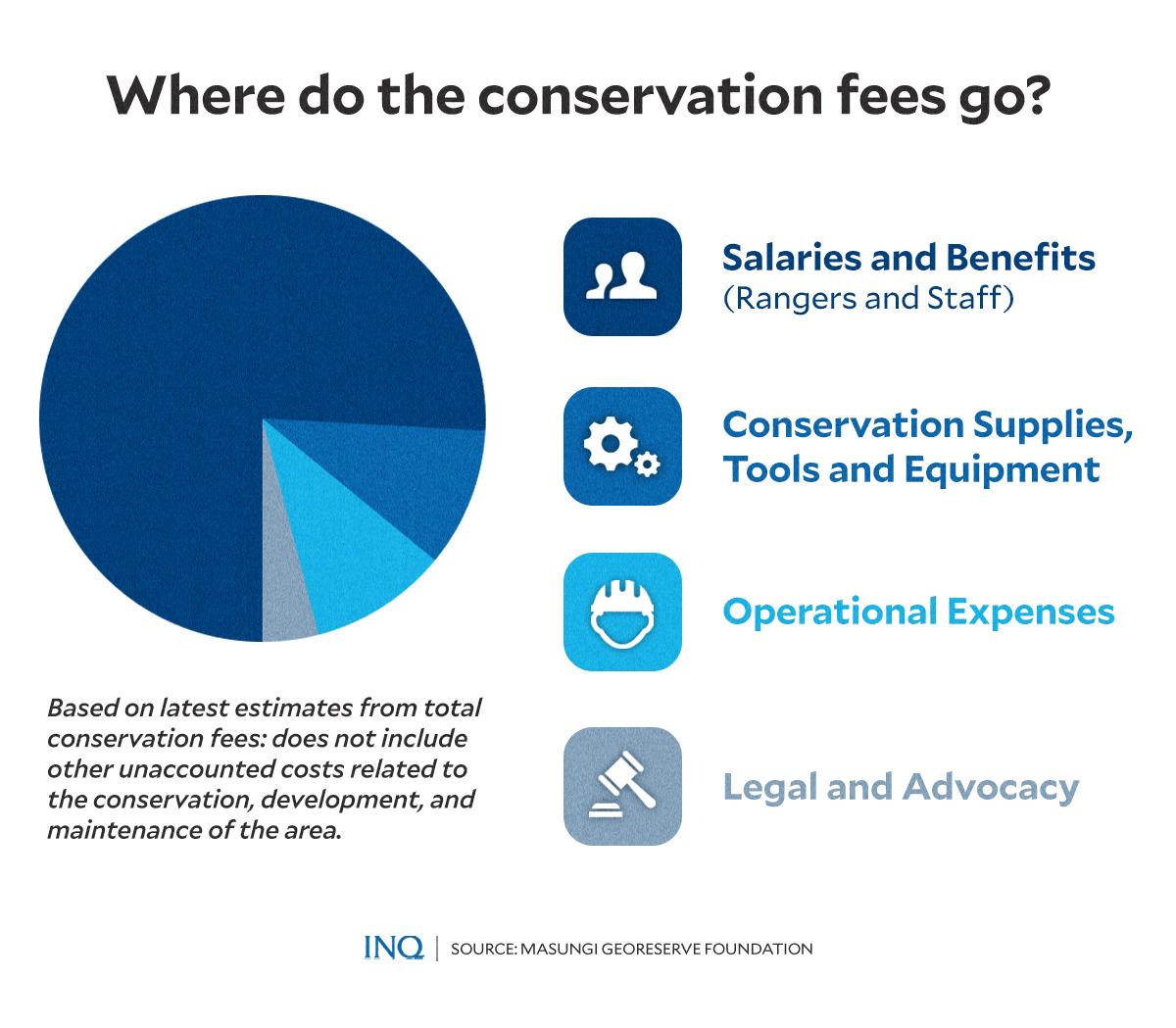

Based on data provided by the MGFI, most, or 75 percent of conservation fees go to the salaries of park rangers, while the rest go to conservation supplies, tools and equipment, operational expenses, and legal costs, especially for park rangers who are confronted with harassment for the work they do.

Sustainable way for change

Dumaliang said that with zero government funding, “the geotourism component of our model fuels our education, research, and protection works,” pointing out that this component makes Masungi Georeserve a sustainable pathway for change-making.

“Without it, we would be reliant on the donation of corporations, which may affect our independence,” she said as she called on the government to talk: “Since the 2017 MOA is an interim agreement […] We can define the term for the agreement as well as detail other mutual concerns.”

As the MGFI said, the MGP “stands as a beacon of environmental stewardship, garnering international acclaim from esteemed bodies such as the United Nations, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the International Ranger Federation, and the World Economic Forum.”

“Its cancellation would not only represent a breach of our international commitments but also a significant setback to our national endeavors in climate action and biodiversity conservation,” MGFI said in its online call “Protect the Masungi Geopark Project.”

READ: Why ‘big threats’ don’t faze Dumaliang sisters in saving Masungi

Dumaliang pointed out that the Philippines has an 80 percent funding gap for biodiversity conservation as the current spending on biodiversity is only at P5 billion a year, based on data from the Biodiversity Finance Initiative, which is working to promote investments in nature.

She explained that protected areas only have an average of P7 to P11 million a year in funding, indicating that the government can only afford to pay one ranger for 4,000 hectares of protected area. There are 94 protected areas in the Philippines, as declared by the Expanded National Integrated Protected Area Systems.

“Models like Masungi [Georeserve] help bridge the management and financing gap in biodiversity conservation and land restoration,” Dumaliang said. MGP has already contributed a lot to the preservation of the protected landscape’s biodiversity and made progress in watershed rehabilitation and protection.

Serious consequences

For Rep. France Castro (ACT Teachers), DENR’s move to cancel the 2017 deal on the protection of the landscape will threaten it as it will open the immense forest land to business development, which could degrade the area again: “This decision could lead to irreversible damage to a critical ecological area.”

READ: DENR plan to void Masungi pact a threat to environment, says lawmaker

As reported by the INQUIRER in March, the MGFI said it had located seven more resorts and private developments within the UMRBPL, which overlaps with the MGP. MGFI said it sent letters to the DENR regarding the presence of illegal structures, but there was no response.

READ: Group managing Masungi tags more ‘encroachments’

“We know that the real objective of this plan is to protect the vested interests in the land. Hence, around 2,000 hectares of forest land will be returned back to syndicates and quarrying companies that have preyed on it before the project,” Dumaliang stressed.

She said that “we and the public including the media have worked hard to stop encroachments in the project site, and the cancellation would mean all our hard work will be lost.” “Thousands of young trees planted by volunteers and visitors would perish.”

“Beyond the physical impacts, the government’s agenda to engage civil society and the private sector in the ecosystem restoration endeavor and climate action will be tainted. Confidence in the Philippines in climate and green financing will fall,” Dumaliang pointed out.

READ: BuCor HQ at Masungi Georeserve: What’s really at stake?