MANILA, Philippines — Lara (not her real name), fell in love with a girl when she was 17. They had a relationship that lasted a year. Now 20, while still not completely out, she engaged in a relationship with a girl again. “Masaya ako (I am happy),” she said.

But in both instances, she said she was initially anxious, saying that while she was really in love, “iniisip ko ‘yung sasabihin ng iba, lalo na ng pamilya ko (I was thinking of what people, especially my family, would say).”

Still, however, Lara stressed that she decided to be in a relationship again because “mahal ko siya at ‘yun ang pinakamahalaga (I love her and that is the most important thing).”

As pointed out by Artemio Millo Jr., a lecturer of sociology at the Ateneo de Manila University (ADMU), “to love and to be loved are a part of being human.” He told INQUIRER.net that “everyone has the capacity to love regardless of gender and sexuality.”

READ: Pride, and how allies can help LGBTQIA+ fight for equality, fair treatment

But as in the case of Lara, to love and be loved as an LGBTQIA+ does not come easy.

She is struggling until now, stressing that while she already told her mother and some of her relatives that she is attracted to people of the same sex, they are still not aware that she already has a girlfriend.

RELATED STORY: Come out for love

Lara, however, learned not to care a lot about what people would say. “Everyone has the right to love and be loved. We all deserve to express how we feel no matter who we are,” she told INQUIRER.net.

After all, more Filipinos now believe that LGBTQIA+ people should be accepted.

Social acceptance

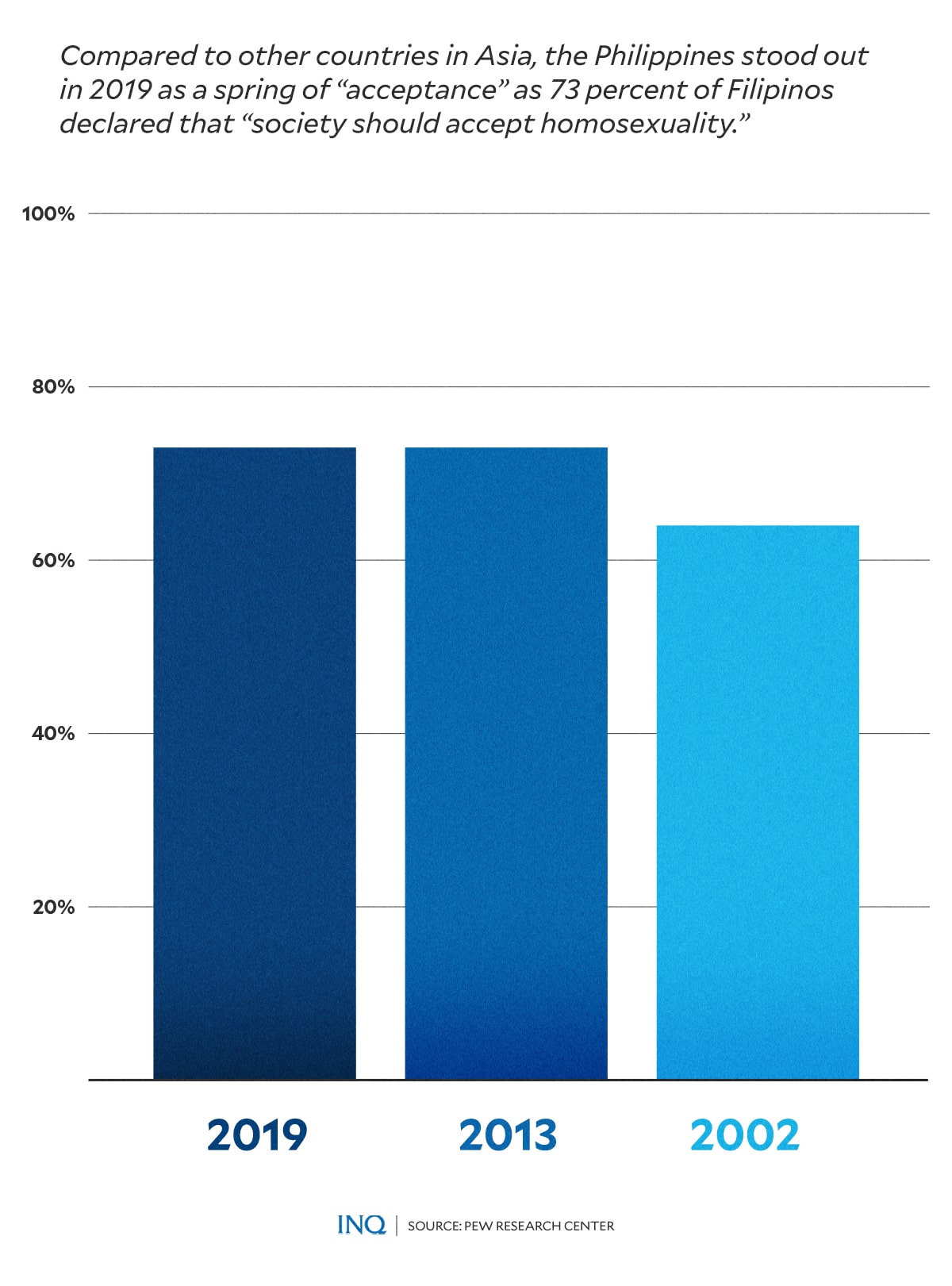

Based on data from the Pew Research Center, compared to the rest of Asia, the Philippines stood out in 2019 as 73 percent of Filipinos declared that “society should accept homosexuality.”

It was the same in 2013 but way higher than the 64 percent in 2002.

Back in 2021, with a 6.06 index score, the Philippines was 36th out of 175 countries assessed by the UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute with regard to social acceptance of LGBTQIA+.

Iceland was on top of the list with an index score of 9.78, followed by the Netherlands (9.46), Norway (9.38), Sweden (9.18), Canada (9.02), Spain (8.77), Denmark (8.69), Ireland (8.41), Great Britain (8.34), and New Zealand (8.23).

But as Millo, who specializes in gay and queer studies, pointed out, “this does not equate to complete acceptance as we have yet to see significant changes from rights to norms.”

Why? Because as he stressed, it would be best to ask this, too: Do LGBTQIA+ individuals, in the same way heterosexuals do, enjoy the same rights and normal activities?

READ: Dark reality: Gay people struggles persist after coming out

As in the case of Mico (not his real name), who had his first relationship with a boy when he was 17, love was not enough to make him feel content: “Ang dami naming hindi magawa dahil sa natatakot kami sa sasabihin ng iba (We cannot do a lot of things because we are scared of what people would say).”

Fighting inequality

But the increasing visibility of LGBTQIA+ relationships is already a win, with Millo linking it with the awareness of LGBTQIA+ individuals regarding “inequalities and the diffusive power of heteronormativity.” “Thanks to social media,” he said.

Millo pointed out that because of awareness through social media, LGBTQIAs+, especially millennials and GenZs, are now more assertive compared to before, saying that as a “geo network”, social media is facilitating interaction, too.

Striving to overcome inequality, this was pointed out by John Torricer, as well. He was 15 years old when he had his first same-sex relationship. He said “I did not really care about what people would think or say because I saw the relationship as ‘love’.”

“We must keep in mind that love is a fundamental human experience, and no one has the right to withhold that love. Love is too beautiful to not be seen,” Torricer, now 20, told INQUIRER.net.

For Millo, the increasing visibility of LGBTQIA+ relationships “invites a rethinking of identity ‘ideals’, too”.

“Self-identifying bakla (encompassing gay, transexuals, bisexuals, etc.) do engage with fellow bakla, which challenges the rigid assumption that bakla is only attracted to the macho ‘lalaki’. There are also those that engage in heterosexual relationships,” he said.

“If we look at [it] more broadly, heterosexuality, homosexuality, and even bisexuality (which are of Western origins) as idealized and fixed bases can no longer make sense to the conditions today,” Millo said.

He pointed out, however, that while LGBTQIAs+ as gender categories (and as a framework) can potentially assimilate into regimes of normalcy and institutions that are dominantly heteronormative, it needs to reflect whether the tide is really inclusive.

Activism is working

But how did Filipinos emerge as people who now accept LGBTQIAs+?

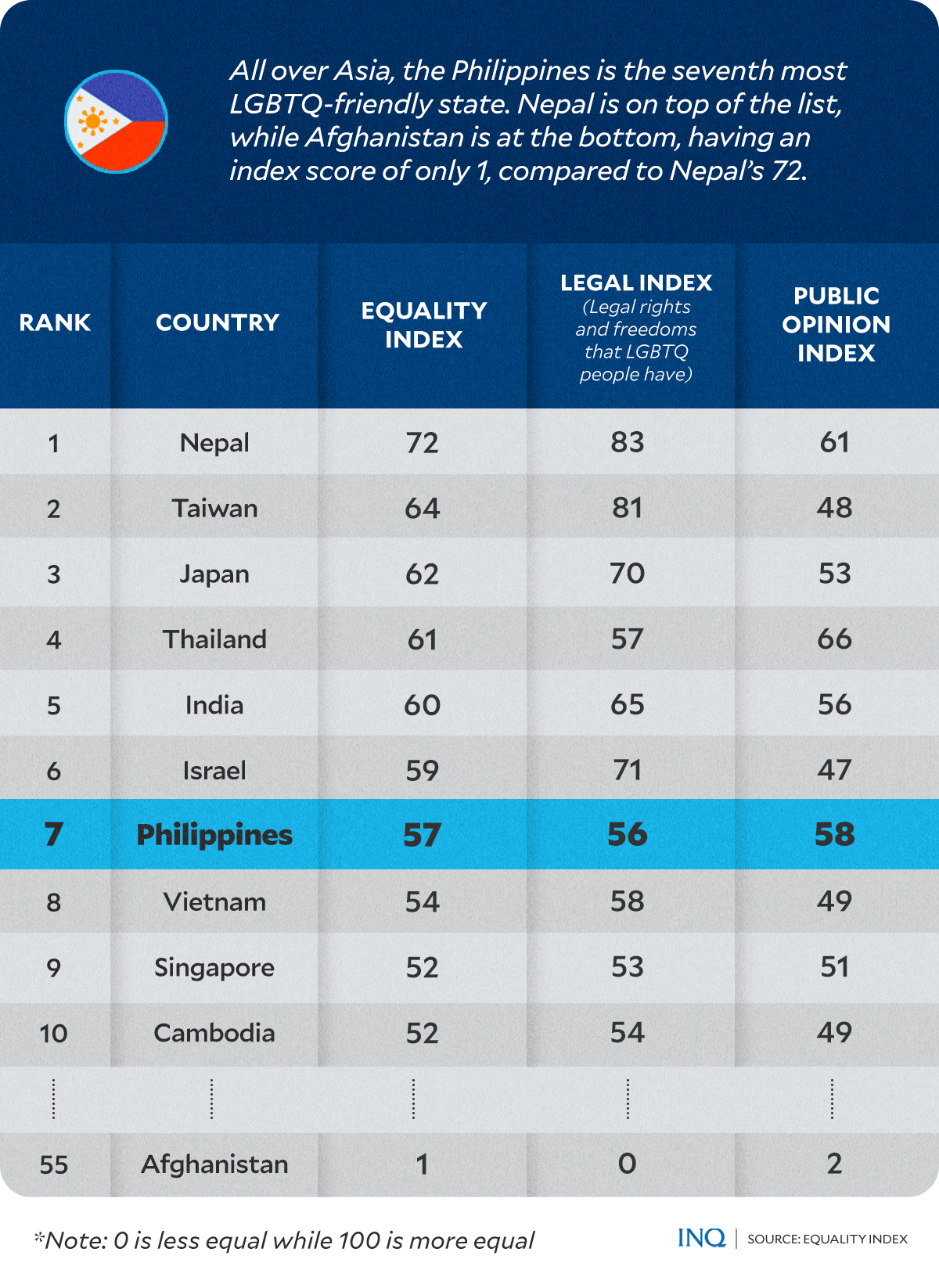

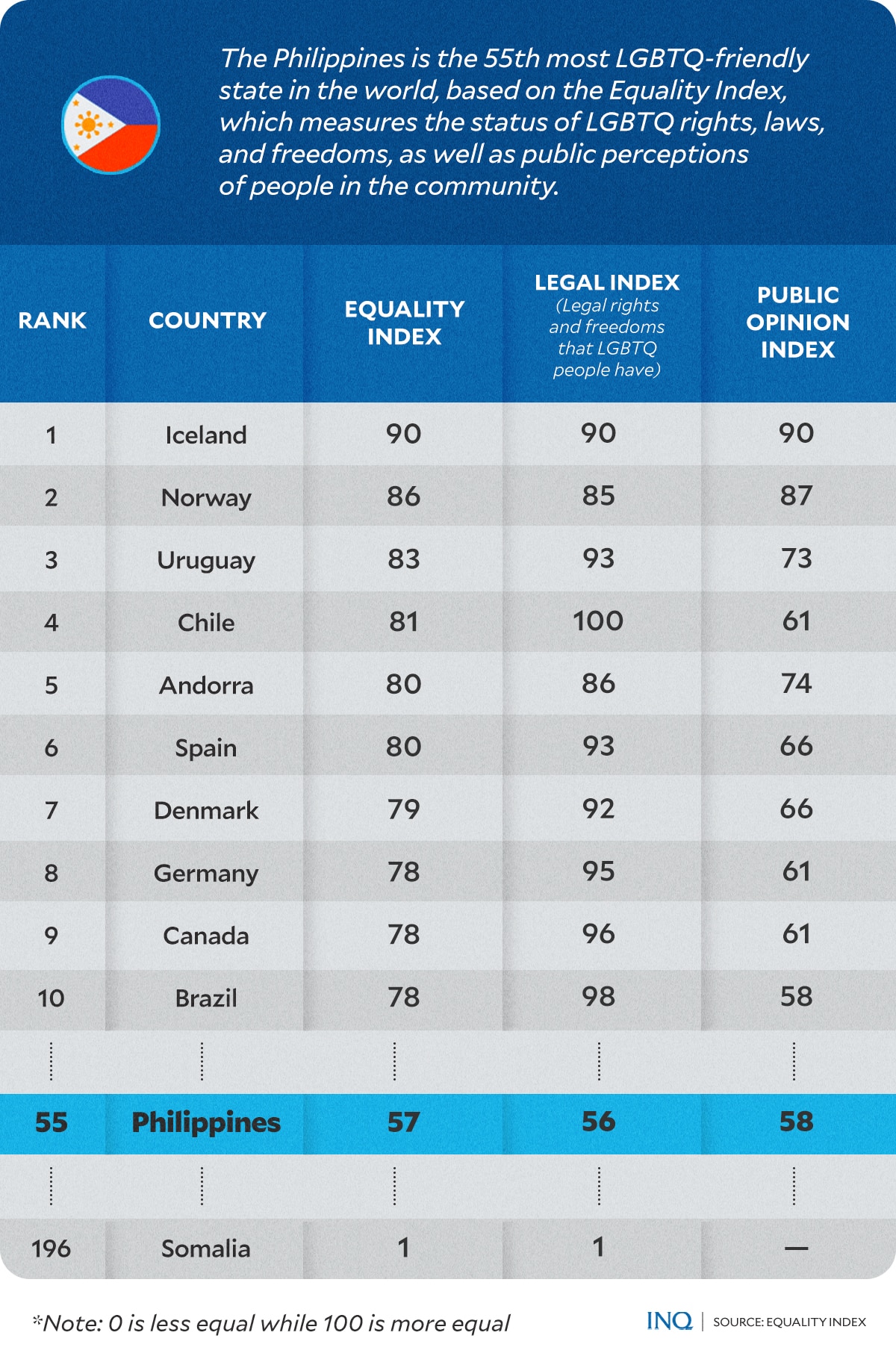

Data from Equaldex’s Equality Index, which measures the status of LGBTQIA+ rights, laws and freedoms, as well as public perceptions, indicated that the Philippines is the 55th most accepting of LGBTQIAs+ in the world and seventh in Asia.

As pointed out by Torricer, the present generation is more accepting rather than tolerant that is why more LGBTQIA+ people are now braver to come out as couples.

READ: Marcos urged to certify SOGIE bill as urgent

It was explained by Millo that acceptance may be because of several reasons such as LGBTQIA+ activism that has become more visible, where individuals, social movements and allied organizations are now seen in traditional or digital spaces.

“There is also a rise of influential leaders from conservative institutions and governments that are supportive of LGBTQIA+ rights […] Although their interests need to be assessed, the private sector is now partaking into the movements,” he said.

He stressed that the fulfillment of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is likewise helping reach a tipping point, saying that select member states are now slowly incorporating policies related to LGBTQIA+ into their domestic agenda.

RELATED STORY: PH rejects same-sex marriage: We’re not ready for that, says DOJ’s Remulla

Millo shared as an example what the ADMU Department of Sociology and Anthropology is doing: “We offer LGBTQIA+ elective courses in alignment with the SDGS.”

Based on the Equality Index, the Philippines has a legal index score of 56. While it was higher than those on the bottom of the list, it was way lower than 90, the highest legal index score, which was received by Iceland in the latest Equality Index.

Cascaded change

It was explained by Millo that different societies may have different social conditions for LGBTQIAs+: “The precolonial Philippines was more egalitarian. There were recorded same sex relationships and there were male Babaylans who cross dressed,” he said.

“However, with colonialism, the bakla got demonized,” he said. “Certainly, it was tougher to engage in same sex relationships before since it was punishable,” he added.

But in contemporary time, the history of LGBTQIA+ movements and emancipation from the West sparked changes. “We now see this cascading to non-Western societies,” he said.

This watershed moment, Millo stressed, can result in restructured local gender ideals, which may possibly empower and disintegrate subjectivities.

“Our sexuality and gender can determine our attraction but these are not the only variables of relationships,” he said. “I think what we need to break free from is the long held idea that the only legitimate kind of love and relationship is the heterosexual love,” he added.

“What enabled that legitimization was formal and informal institutions such as religion, state, laws, etc. This means legitimization is a social construct and gets ‘naturalized’ over time,” Millo said.

For Torricer, “it is inevitable that same sex couples still face discrimination and sadly, hatred from people who think that they have authority to exercise over people’s lives or choices. It is the battle that the current generation is trying to deviate from.”

RELATED STORY: 5,000 LGBTQIA+ get P5,000 cash from DSWD for Pride Month