Bats part of success (not horror) story at reforested Bicol site

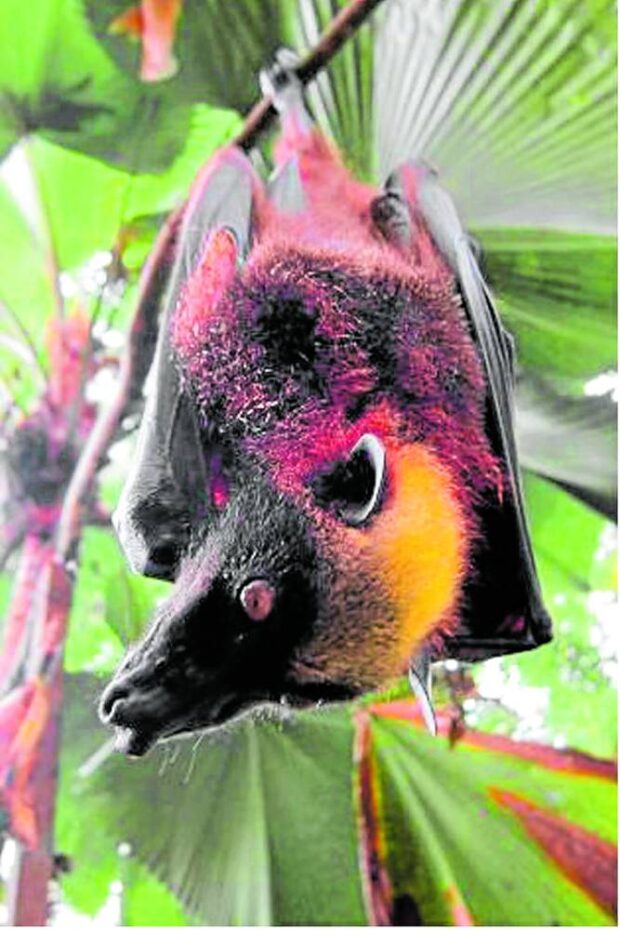

SILENT SOWERS | The “kabog,” as it is known in Bicol, is the “flagship species” among the flora and fauna being protected at the reservation site (lower photo) of the Energy Development Corp.’s Bacon-Manito Geothermal Project. Bats are natural seed spreaders that can help reforest denuded and inaccessible mountain ranges. (Photo by GREGG YAN / Energy Development Corp.)

MANITO, Albay, Philippines — “We were on a motorcycle one night when I noticed a shadow on the road. I looked up and saw what seemed like a large bird. I thought it was an aswang! I could even hear the loud flapping of its wings,” recalls Fatima Espineda from Gubat, Sorsogon. “Eventually though, I realized that it was just a very large bat.”

That “aswang” turned out to be a golden-crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus)—the largest bat on Earth (and the possible origin of the “manananggal,” “tiktik,” plus the other flying fiends and ghouls of Pinoy children’s nightmares).

Cornell College’s Dr. Tammy Mildenstein, a wildlife conservationist, once pointed out how similar folkloric creatures geographically overlapped with the distribution of large bats. Malaysia has its own version of the manananggal—the “pennangalan.” In Bali, Indonesia, it’s the “leyak.” In Thailand, the “krasue.” Darkness and superstition have always potently spurred people’s imaginations.

Creatures of the night, bats are often treated with fear and distrust: even the Dark Knight of Gotham City was scared of them.

This Halloween, it’s time to debunk the myth that bats are dangerous pests and worse.

‘Incredible diversity’

The Philippines has 79 recorded bat species, half of which are endemic or found nowhere else on the planet. North America, with a land area that’s 66 times larger — has but 45.

“We have an incredible diversity of bats since each of our 7,100 islands is geographically unique,” explains Dr. Mariano Roy Duya of the University of the Philippines Institute of Biology. “And of course, we are home to the largest bat of all.”

One of the endemic species is the “kabog” or golden-crowned flying fox, which weighs over a kilo when fully grown and has a wingspan of nearly 2 meters tip to tip. An elongated snout, optimized for feeding on fruits, makes it look curiously foxlike. Its distinctive golden head exquisitely contrasts with its chocolate-brown body.

Alas, conspicuous and hefty, it’s been hunted for generations.

“I learned to shoot kabog with an air rifle when I was still in elementary school [in the 1990s],” recalls Joseph Gabion. “They’re easy to hunt by day because they hang upside down from their roosts… Kabog meat has a slightly woody taste.”

PROTECTED | The golden-crowned flying fox is the largest of the world’s 1,400 known bat species. It is considered endangered and legally protected under Republic Act No. 9147. Killing one is punishable with a fine of from P20,000 to P1 million and/or a prison term of one to 12 years. (Photo by GREGG YAN / Energy Development Corp.)

READ: Samal Island reaps rewards of conservation: 2.5M bats!

READ: Boracay fruit bats unseen for 2 years

Lost to kaingin

But that was back then. Gabion—a member of the Civilian Armed Forces Geographical Unit (Cafgu) of the Armed Forces of the Philippines—now counts himself as both a peacekeeping officer and a protector of the local forest. His Cafgu contingent helps look after the Bacon-Manito Geothermal Project (Bacman) site, which straddles the provinces of Albay and Sorsogon.

The bats’ roosts are now protected by the Energy Development Corp. (EDC), the company behind Bacman, and its conservation partners.

Due to centuries of hunting and deforestation, golden-crowned flying foxes are classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature as endangered.

“Bats are protected by Republic Act 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, which also protects the habitats they live in,” notes forester Marlon Francia, the Provincial Environment and Natural Resources officer of Sorsogon.

Bats are shielded by law from hunters, but their leading killer is unchecked forest loss—particularly from destructive upland clearing practices like kaingin.

“Kaingin is used to open up an area for agricultural purposes, usually by burning down trees. This threatens not just bats, but all animals which lose their habitats or their main sources of food,” adds forester Keith Dimaranan of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Region 5.

Natural seed dispersion

Thankfully, they still have some safe havens.

With no less than 12 active and inactive volcanoes, Bicol is virtually a land of fire. Its vast reservoir of heat below the Earth’s surface makes the region productive in geothermal power. Nestled between the provinces of Albay and Sorsogon lies EDC’s Bacman project site, a 25,000-hectare reservation that still hosts an impressive array of wildlife, including a sizeable population of flying foxes.

Ed Jimenez, corporate relations head for the project, points to a verdant mountain range a kilometer away. “Believe it or not, this entire mountain range was once logged-over. The only trees left were the ones loggers ignored. To bring the mountain back to life, we worked with the local communities to help reforest this area while providing them with an alternative source of income.”

“Decades later, the organizations we helped form, like the Alliance of Bacman Farmer’s Association Inc. Agriculture Cooperative (formerly Albafai) and the Bacman Host Community Multipurpose Cooperative, have become some of our most passionate champions. Even the grandchildren of the original members are helping us plant trees, promote community-based conservation and protect these forests,” Jimenez said.

Flagship species

“Though millions of trees have been planted under the Binhi Program, we should still recognize the importance and effectiveness of natural seed dispersion—either by the wind, water or by local wildlife,” explains forester Abegail Gatdula, project manager of EDC’s Flagship Species Initiative (FSI). “Flying animals like birds and bats eat the fruits of various forest trees and disperse them far and wide within life-giving guano bombs, giving the seeds a vital head start.”

Representing iconic wildlife found in its geothermal, solar and wind sites, EDC’s FSI aims to popularize some of the nation’s lesser-known forest denizens. “Our flagship fauna species in Bacman is the golden-crowned flying fox, with over 700 individuals recorded,’’ Gatdula said.

“For flora, it’s the ‘mapilig’ (Xanthostemon bracteatus), which has one of the hardest types of wood of any tree in the country,” shares forester Neil Miras, EDC Bacman’s watershed management officer.

The seven other flagship species include the Philippine warty pig (Sus philippensis), Visayan hornbill (Penelopides panini), “Apo myna” (Goodfellowia miranda), plus native trees like “katmon bayani” (Dillenia megalantha), red lauan (Shorea negrosensis), almaciga (Agathis philippinensis) and “igem-dagat” (Podocarpus costalis).

As the country’s largest provider of clean and renewable energy, EDC has been reforesting the Philippines since the early 1980s, since geothermal plants require healthy forests for optimal power generation.

Quiet planters

All along, golden-crowned flying foxes, birds and other bat species have been quietly doing their part to make the Philippines greener.

“Think of them as the ‘seed planters’ of nature. We never pay them but they keep working for our world,” says Jean Dayap, Municipal Environment and Natural Resources officer of Manito in Albay.

Gabion, the former bat hunter, could only agree: “I’ve seen firsthand how a forest can regrow. That mountain was covered by nothing more than cogon grass a few decades ago. Look at how lush and beautiful it is today. Wild animals like bats are very important to nature.”

Though generally shunned—and sometimes mistaken for an aswang—bats deserve the limelight this Halloween. Tonight, please look up at the night sky to thank our silent heroes, who forever work the night shift to help restore our forests—even if it’s just one guano bomb at a time.