Good government index: PH rank falls but disaster response improves

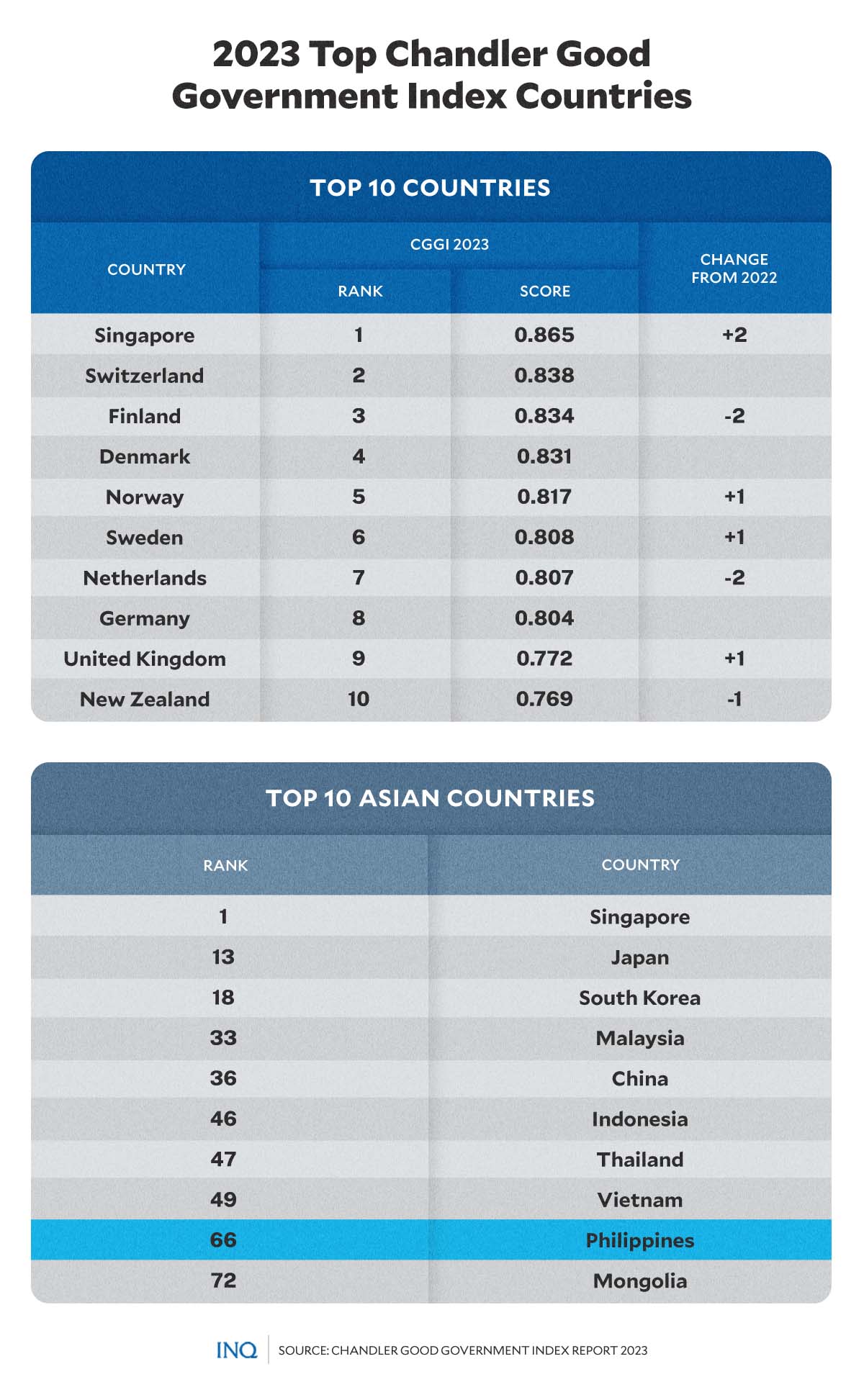

MANILA, Philippines—Despite developments in the country’s disaster risk reduction management in the past years, the Philippines’ good governance index ranking slipped by three spots to 66th out of 104 countries.

In the third iteration of the Chandler Good Government Index (CGGI) report, which measures the capability and effectiveness of governments across the globe, the Philippines’ ranking fell from 63rd in 2022 and 61st in 2021—making the current ranking the country’s worst performance yet.

Although the Philippines was among the top 10 Asian countries ranked in the CGGI, it lagged behind Singapore (ranked 1st), Japan (13th), South Korea (18th), Malaysia (33rd), China (36th), Indonesia (46th), Thailand (47th), and Vietnam (49th)—and was ahead of Mongolia (72nd).

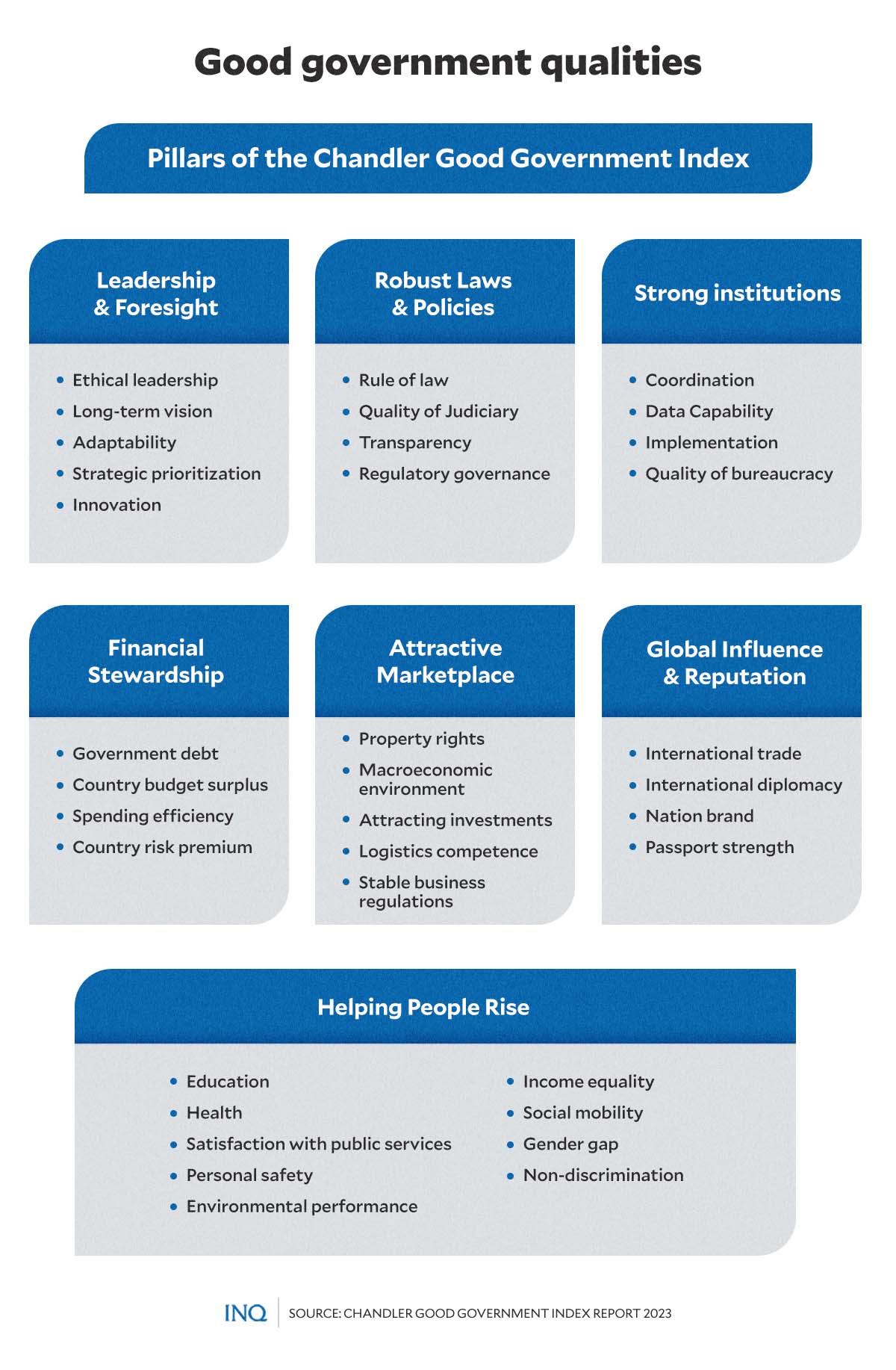

The index is based on 35 indicators across seven pillars: Leadership & Foresight; Robust Laws & Policies; Strong Institutions; Financial Stewardship; Attractive Marketplace; Global Influence & Reputation; and Helping People Rise.

According to the international non-profit organization Chandler Institute of Governance (CIG), the third annual CGGI report focuses on why good governance is critical amid the “polycrisis”—the combined impacts of war, climate shocks, deadly pandemics, refugee crisis, and rampant inflation worldwide.

“Clearly, national governments aren’t solely responsible for how a country manages a crisis. International organisations, civil society, businesses, citizens—all have a role to play,” said CIG.

“And at a time when crises are global, international cooperation matters hugely, whether that’s working with other governments, or non-state actors like scientific coalitions, trade bodies or international finance organisations,” it added.

However, CIG stressed that a polycrisis poses difficult questions, such as:

“How can a government cope with relentless change and uncertainty? How do they learn to maintain stability while adapting effectively? How can they distinguish what are the most important capabilities required, and then assess for themselves their own government’s strengths and weaknesses?”

“The CGGI was built to help answer questions precisely like these.”

Improved disaster response

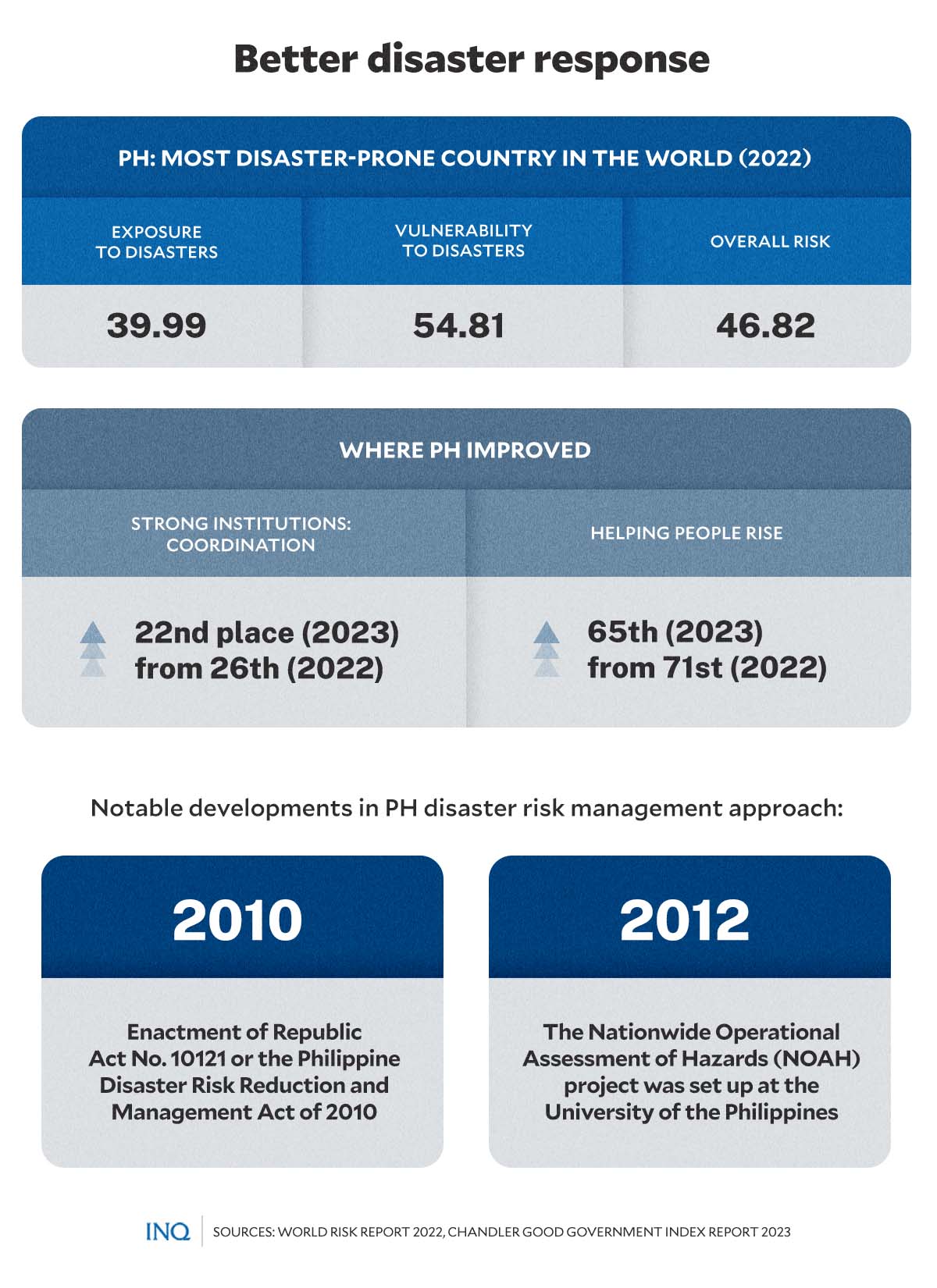

Despite dropping a few notches in the 2023 index, the CGGI noted some developments in the country’s disaster risk management approach.

The Philippines—identified as the most disaster-prone country in the world due to its high risk, exposure, and vulnerability to disasters and calamities—suffers from one of the highest annual projected losses from hazards and disasters, compared to its Southeast Asian neighbors.

READ: PH most disaster-prone country in the world—study

According to a study by global professional services company GHD, the Philippines—which is hit by an average of 20 typhoons every year—is expected to lose $124 billion until 2050 from water-related risks, like strong storms, intense floods, and prolonged droughts.

READ: PH loss from too much, or zero, water seen to hit $124B of GDP

These losses, the CIG noted in its report, have pushed the government to improve the country’s disaster risk and reduction management efforts.

Data showed that the country’s global ranking for the Coordination indicator, which is under the Strong Institutions pillar, improved from 26th place last year to 22nd place in 2023.

The Coordination indicator highlights the government’s “ability to balance interests and objectives, and to ensure that multiple government agencies act coherently and in a collaborative manner.”

The CGGI added that the country’s ranking in governance outcomes, under the Helping People Rise pillar, moved up by six notches—“buoyed by significant progress in Satisfaction with Public Services and Health.”

“Governments that use their capabilities to create conducive conditions for people from all walks of life to achieve their fullest potential are Helping People Rise. Good public outcomes mean enhanced opportunities and a better quality of life for people; these, in turn, improve trust in government,” the CGGI stated.

PH DRRM efforts

The improvements in the Philippines’ disaster risk management approach, as mentioned by CIG, were due to the enactment of Republic Act No. 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010.

Under RA No. 10121, the National Disaster Coordinating Council (NDCC) was renamed National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC).

Among its many functions and responsibilities is to advise the president on the status of disaster preparedness, prevention, mitigation, response, and rehabilitation operations being undertaken by the government, civil society organizations, private sector, and volunteers.

READ: Moving NDRRMC to Office of the President: What difference will it make?

“This move was seen as a paradigm shift in the country’s approach to disaster management. The NDRRM Council had clearer and more comprehensive powers, an expanded mandate including disaster preparedness, and a broader stakeholder reach,” the CIG explained.

“Instead of only responding to disasters, the Philippines would shift towards more proactive disaster preparedness and mitigation, and a more holistic and comprehensive inter-agency and multi-sectoral approach,” it added.

The report also stressed the partnerships between the government and academia to produce better data that can be used for “decision-making in integrated disaster prevention and mitigation.”

Such partnerships have led to the creation of the Nationwide Operational Assessment Hazards (NOAH) project, which was set up at the University of the Philippines (UP) in 2012.

“Project NOAH provides open access to accurate, reliable, and timely hazard and risk data to allow national government agencies, private sector, academia partners, and the public to make informed decisions for disaster risk reduction activities,” said CIG.

“Project NOAH won an honourable mention in the Averted Disaster Award 2022, which aims to recognise successful disaster mitigation interventions around the world.,” it continued.

Low indicator scores

Across the 35 indicators, one of the lowest scores for the Philippines was under the Passport Strength indicator, which measures the credibility of a country’s passport—“as measured by the number of visa-free arrangements that passport holders enjoy globally.”

The country got a 0.22 score, which was below the global average score of 0.57.

Earlier this year, the Philippines ranked 78th out of 109 in the 2023 Henley Passport Index (HPI)—which compares the visa-free access of 199 passports of different countries to 227 travel destinations.

READ: PH passport places 77th in 2023 Henley Passport Index

The Philippines likewise received a low score for the Implementation indicator, which assessed the government’s ability to execute its own policies and meet its policy objectives. Compared to the global average score of 0.37, the country got a 0.09 score.

In terms of the safety and sustainability of ecosystems and environment in the Philippines (Environmental Performance indicator), the country was given a score of 0.12 which was below the 0.51 global average score.