Damage, impact of oil spills in PH

COMPOSITE IMAGE: JEROME CRISTOBAL FROM INQUIRER STOCK, PCG AND Office of Cebu Rep. Luigi Quisumbing PHOTOS

(Last of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines—Oil spills, often considered as “environmental disasters,” cause a wide range of damage to the marine environment, some irreversible.

Over the past decades, the Philippines has seen several devastating oil spills. Most, if not all, of these have led to significant damages, loss of livelihood, costly clean-up operations, and years-long recovery periods.

The most recent occurred last week, when a tanker carrying 800,000 liters of industrial fuel capsized at Balingawan Point in Tablas Strait near Naujan and the island province of Marinduque after it experienced engine trouble.

READ: PCG: Oil tanker off Oriental Mindoro now fully submerged, oil spill worsens

Marine experts from the University of the Philippines-Diliman College of Science Marine Science Institute (UPD-CS MSI) warned that over 24,000 hectares of coral reef may be at risk as the spill continues to spread due to strong winds and waves.

READ: Over 24,000 hectares of coral reef at risk following Mindoro oil spill

In this article, INQUIRER.net will detail the damage and impact of massive oil spills — based on two of the most devastating cases that have occurred in the past years.

Mangroves affected, damaged

In the Philippines, which is hit by at least 20 typhoons yearly, mangroves and beach forests contribute largely to coastal protection. These help mitigate the adverse effects of typhoons on people and livelihoods.

READ: Mangroves save lives: Greenbelt zones pushed in PH

Unfortunately, while mangrove and beach forests are known as adaptable ecosystems, they are found to be highly vulnerable to oil toxicity.

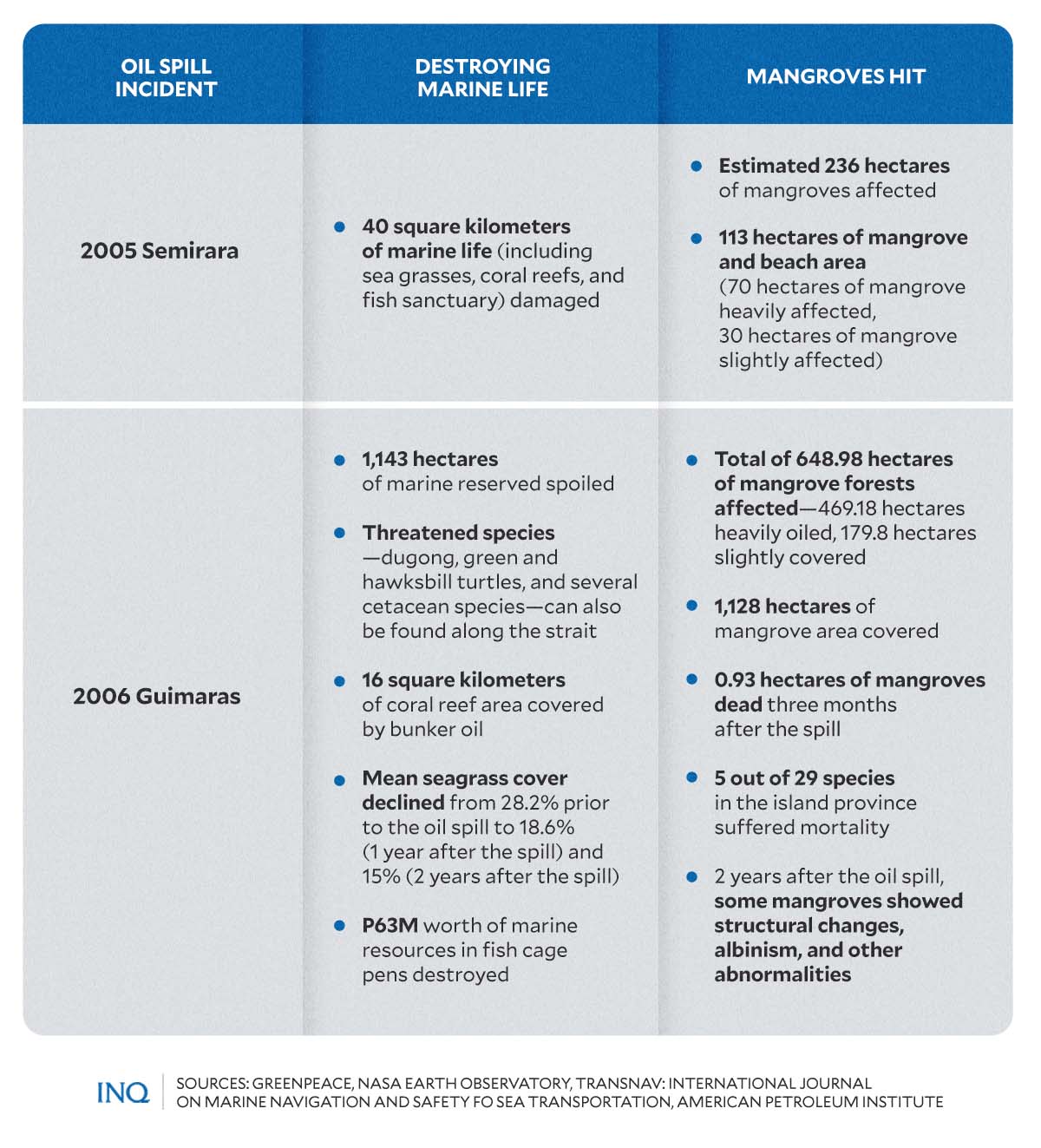

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

In previous years, hundreds of hectares of mangroves and beach areas across the country’s coastal areas have been heavily hit by massive oil spills. The extent of damage could range from changes in appearance to defoliation or death of mangroves.

In December 2005, when an oil barge of the National Power Corp. (Napocor) capsized off the shore of Semirara in Antique, spilling almost 200,000 liters of oil, an estimated 236 hectares of mangrove forests were affected — most of it covered in thick bunker fuel oil.

READ: PH oil spills: What history and data tell

Environmental group Greenpeace previously released data on the range of damage caused by the oil spill.

The group estimated that about 113 hectares of mangrove and beach area in the coastal island were hit by the widespread oil slick—70 hectares were found to be heavily affected, while 30 hectares were slightly affected.

A year later, in August 2016, strong winds and high waves battered the oil tanker M/T Solar I off the southern coast of Guimaras while it was carrying 2 million liters of bunker fuel from Petron Corp.

The spill, considered by experts the worst in the country’s history, has affected 1,128 hectares of mangrove area — based on data released by the government.

Additional reports said the spill affected at least 648.98 hectares of mangrove forests in the province of Guimaras. Around 469.18 were heavily oiled, while 179.8 hectares were slightly covered.

Three months following the oil spill, at least a hectare of mangroves in the coastal area died.

A 2014 study by scientists Dr. Resurrecion B. Sadaba and Dr. Abner Barnuevo further detailed that out of 29 marine species in Guimaras, five exhibited mortality, including Avicennia marina, Rhizophora apiculata, R. mucronata, R. stylosa, and Sonneratia alba.

They also noted that some mangroves showed structural changes, albinism, and other physical abnormalities two years after the oil spill.

“The M/T Solar I oil spill in Guimaras impacted the mangrove forest in varying degrees from acute and lethal damages to sublethal stresses depending on the location and species-specific,” Sadaba and Barnuevo explained.

“Acute effects involved yellowing of leaves defoliation and mortality while long-term effects involved the appearance of albino propagules manifested in R. stylosa and reduction in canopy cover and leaf sizes [in some species],” they added.

Marine life threatened

Aside from mangroves and beach forests, oil spills also damage local marine ecosystems and threaten various fish and other species.

Greenpeace estimated that around 40 square kilometers of marine life were contaminated by the bunker oil that spilled from the sunken barge in Semirara in 2005. These include seagrasses, coral reefs, areas for shellfish, and livelihood seaweed projects.

The damage were more significant during the 2006 Guimaras oil spill, which spoiled 1,143 hectares of marine reserve, and covered 16 square kilometers of coral reef with bunker oil.

Government data also found that 58 hectares of seaweeds plantation were affected in Nueva Valencia, San Lorenzo, Sibunag, Guimaras and Ajuy, Iloilo

The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) estimated that around P63 million worth of marine resources in fish cages and fish pens have been destroyed.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

A study published in 2009, which focused on the effects of the oil spill on seagrass meadows in Taklong Island National Marine Reserve (TINMR)—a marine protected area—noted several structural changes.

Seagrass meadows, according to scientist and the study’s author Dr. Marie Frances Nievales, serve as nurseries, breeding grounds, and homes to many marine fishes, reptiles, and invertebrates with important economic, ecological, and conservation value.

“In Guimaras, seagrass meadows serve as center of economic activity (e.g. shellfish gleaning, seaweed farming, sea cucumber collection and fishing using gill nets). These economic activities were hampered by the oil spill,” Nievales said.

The study said that seagrass meadows located in the shoreline of CALAPARAN experienced several impacts following the oil spill, including:

- a decrease in seagrass cover and shoot density;

- generally lower seagrass cover, shoot and blade densities, and above-ground biomass within a year after the oil spill;

- a lower mid-year peak in seagrass cover as part of a bimodal seasonal pattern; and

- a prolonged decline in shoot and blade densities within a year of the oil spill.

The mean seagrass cover, according to Nievales, declined from 28.2 percent before the oil spill to 18.6 percent one year after the spill. It further dropped to 15 percent two years after the incident.

“The area is tremendously rich in marine life,” said WWF’s Dr. Jose Ingles. “A spill of this proportion is simply catastrophic.”

Economic impact

Massive oil spills result in substantial economic losses.

Based on data from Semirara Mining & Power Corp., the 2005 oil spill has impacted the province’s seaweed livelihood project, affected 21 families, and left 420 cages damaged. The estimated cost of damage amounted to P4.5 M.

A separate study found that a clean-up project, which was planned to last for six months following the incident, was estimated to cost P90 M. Napocor estimated that it has spent some P19 M for the clean-up operation on the island.

In Guimaras, the 2006 oil spill contaminated the waters, leading to a halt in fishing activities. Around 20,000 fishers across the islands of Guimaras, Panay, and Negros lost income.

“Women have stopped gathering shells while men can no longer fish because of the oil spill in Guimaras,” the non-profit organization World Vision previously reported.

“Worse, even the areas in Guimaras and Iloilo not directly hit by the oil spill also suffer the brunt of economic deprivation. People do not want to buy any marine products (fish, shrimps, oysters) that come from Iloilo and Guimaras.”

The island’s tourism, which has been a huge part of Guimaras’ economic activity, also took a hit. The Department of Tourism (DOT) previously stated that the island suffered an estimated P3.95 million worth of tourism revenue losses.

Long recovery period

Unfortunately, the recovery process following oil spills costs a lot and takes a very long time.

“In time, natural recovery processes are capable of repairing damage and returning the systems to its normal functions. The recovery process can be assisted by removal of the oil through well-conducted clean-up operations, and may sometimes be accelerated with carefully managed restoration measures,” the International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation (ITOPF) explained.

“However, in most cases, even after the largest oil spills, the affected habitats and associated marine life can be expected to have broadly recovered within a few seasons,” it added.

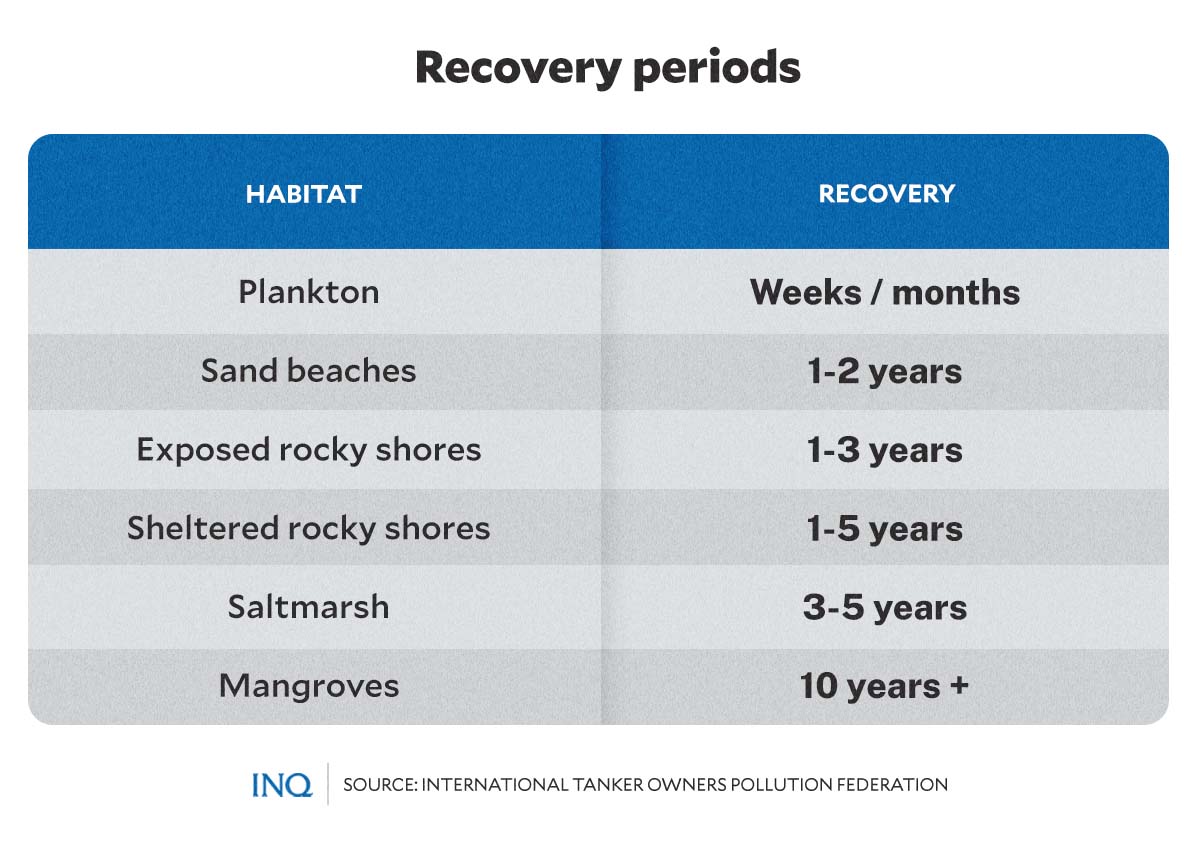

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Following the oil spill, habitats may begin to function normally within a certain period, depending on many factors, such as the amount and type of oil spilled.

For example, ITOPF said it would take at least 10 years or longer for mangroves to recover or function normally again after an oil spill. On the other hand, plankton would only need weeks or months to recover.

“Organisms living within the mangrove ecosystem can be impacted both by direct effects of the oil and also the longer term loss of habitat,” ITOPF said.

“Natural recovery of the complex mangrove ecosystem can take a long time and reinstatement measures may have real potential to accelerate the recovery process in such habitats,” it added.

The ITOPF also noted that while effective clean-up operations usually help reduce the geographical extent and duration of pollution damage, aggressive clean-up methods have been found to cause additional damage over time.

According to Sadaba, following the Semirara oil spill, several responders went inside mangrove forests for clean-up operations—hoping to contain the oil that had reached the shores.

However, some responders might have stepped on the mangroves, leading to more damage.

The recovery process after the devastating oil spill in Guimaras Island continued years after the incident. In 2011, five years after the spill, scientists said the island’s marine resources continue to be affected by contamination.

“We cannot yet say that there has been a full recovery five years after the oil spill. But there are encouraging signs of recovery and growth,” said Lemnuel Aragones, professor at the UP Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology.