Fighting sexual predators vs women in health sector an urgent task

(Last of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines—The sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment (SEAH) of women in the health sector worldwide persists. Unfortunately, the harrowing experiences of victims remain untold.

A policy report by Women in Global Health (WGH), which analyzed 235 stories of SEAH from women in the health sector from 40 countries, found that women health workers across the globe experience work-related SEAH.

These unwanted and unprovoked experiences varied from sexualized verbal abuse to sexual assault and rape.

The stories submitted to WGH through the #HealthToo platform last year showed that many women in the health sector became victims of different kinds of SEAH, inflicted mainly by male perpetrators—including co-workers, patients, and men in communities—most of whom hold higher positions or power.

Article continues after this advertisementMany male perpetrators appear to be serial abusers, enabled by ‘silent bystanders’ supporting a patriarchal culture that legitimizes, downplays, and perpetuates SEAH against women,” the WGH explained.

Article continues after this advertisement“Many stories describe sexist behavior that belittles and demeans women, motivated by reinforcing power differentials and stereotypes of women’s subordinate position, and less by sexual desire,” it added.

READ: Sex predation looms large for women health sector workers

Unfortunately, these traumatic experiences are often downplayed and normalized in the health sector. This often pushes victims not to make an official complaint or report.

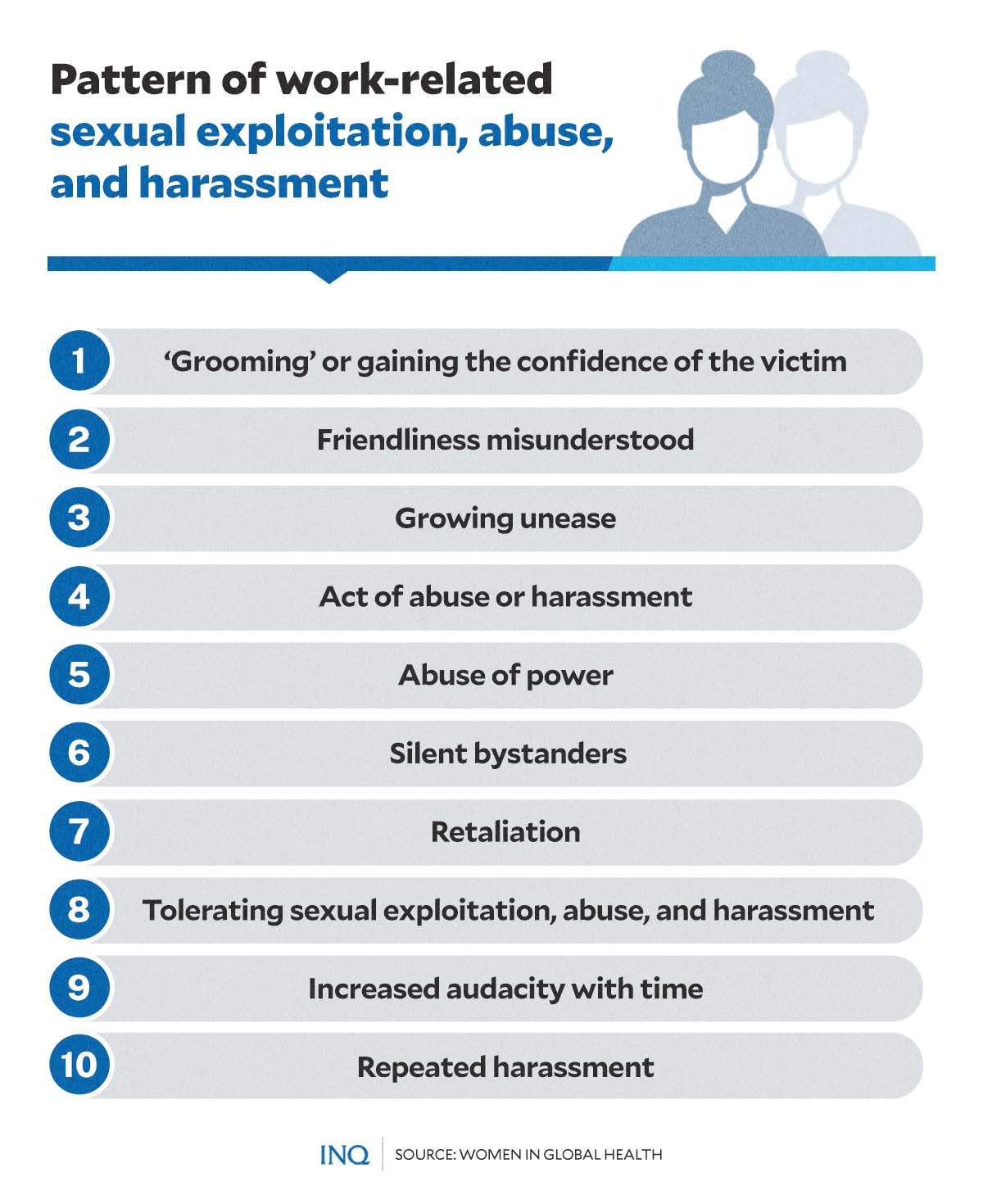

Patterns of abuse

From the narratives shared by women survivors in the health sector worldwide, typical SEAH patterns of abuse emerged.

This involves a ten-step pattern, which was identified as:

- Step 1: ‘Grooming’ or gaining the confidence of the victim — perpetrator behaves cordially initially and appears to help the intended victim to gain trust.

- Step 2: Friendliness misunderstood — the intended victim learns to trust the perpetrator and misunderstands their cordiality to be well-intentioned.

- Step 3: Growing unease — the victim feels a growing sense of unease due to an unequal power relationship; harassment towards the victim may be masked as humor or a ‘joke.’

- Step 4: Act of abuse or harassment — the feeling of discomfort in survivors is soon followed by the actual act of abuse or harassment and realization by the victim that the perpetrator cannot, after all, be trusted.

- Step 5: Abuse of power — a perpetrator in a higher position may abuse their power to silence or coerce the victim.

- Step 6: Silent bystanders — bystanders who may see abuse or hear about it chooses to keep quiet.

- Step 7: Retaliation — perpetrator’s behavior may become more abusive, and they may respond with violent behavior or passive aggression when threatened with exposure.

- Step 8: Tolerating SEAH — power imbalances that lead to SEAH may back women into a corner in fear of losing their income, jobs, career advancement, or honor and reputation.

- Step 9: Increased audacity with time — silence and tolerating SEAH will lead to an increased audacity by the perpetrator.

- Step 10: Repeated harassment — the cycle completes, and the perpetrator continues the act of SEAH with the same victim or other victims.

“This is a pattern of abuse that [men] have perpetrated on a series of women, often emboldened or enabled by others in senior positions who are aware and ‘turn a blind eye’ or have heard rumours and choose not to investigate,” the report noted.

“All the stories suggest that unequal power dynamics is a major enabler of SEAH,” it added.

Damaging impacts

Work-related SEAH—which includes a range of sexualized behavior, including both non-verbal, verbal, and physical abuse—causes damage to victims and women survivors in the health sector.

The immediate and long-term effects of SEAH on women health workers include physical and mental harm. Gender inequities and abuse of power likewise damage a woman’s career, undermine her performance at work, and diminish her sense of self-worth by fostering a hostile work environment.

WGH also found that many victims who have shared their experiences have described incidents as “vivid traumatic memories.”

“Trauma is an emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, rape, or natural disaster. Immediately after the event, shock, and denial are typical responses,” the organization explained.

“Survivors’ concern that someone will hurt them triggers automatic responses: often described as flight, fight, freeze or fawn,” it added.

Trauma response among victims of SEAH could be divided into two types—the immediate trauma response to the situation and the long term trauma response if the trauma does not get resolved.

Unpredictable emotions, flashbacks, strained relationships, and physical symptoms (such as nausea and headaches) are just among the possible long-term impacts of abuse.

Other longer-term physical and mental harm caused by SEAH—based on #HealthToo stories—include unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and lasting damage.

“#HealthToo stories record the trauma of women victims from SEAH in the health sector, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicidal thoughts. Employers are failing in their most basic duty of care,” the report stressed.

“SEAH hinders women’s career progression and retention in the health workforce, affecting morale, mental health, sickness, absenteeism, turnover and therefore, increasing staff shortages.”

Underreported, unrecorded

Widespread SEAH and sexual violence, both work-related and outside work, however, remain underreported and under-documented.

A joint analysis by the International Labour Organization, Lloyd’s Register Foundation (LRF), and analytics company Gallup found several factors preventing victims from talking about and even reporting their experiences.

These factors include fear of stigmatization, lack of knowledge of reporting and monitoring systems, “normalization” of violence and harassment, and re-victimization or retaliation.

Women victims of sexual violence and harassment across all sectors also cited the following reasons for not reporting:

- “waste of time” (62 percent)

- “fear for their reputation” (54 percent)

- “worried people at work would find out” (51 percent)

- “unclear what to do” (43 percent)

Meanwhile, the following reasons for not reporting emerged from the #HealthToo stories:

- lack of knowledge about SEAH

- fear of retaliation and blame

- reducing the severity of abuse

- absence of reporting authority

- lack of trust in authority

- lack of proof

“The majority of women reporting to #HealthToo did not make an official complaint or report SEAH. Some lacked a reporting mechanism, others feared disbelief, stigma or retaliation,” WGH’s policy report stated.

“Without victim-centered reporting mechanisms, SEAH is unrecorded, unsanctioned, and has a cost primarily for the victim, while the perpetrator is enabled to continue the pattern of behavior,” it continued.

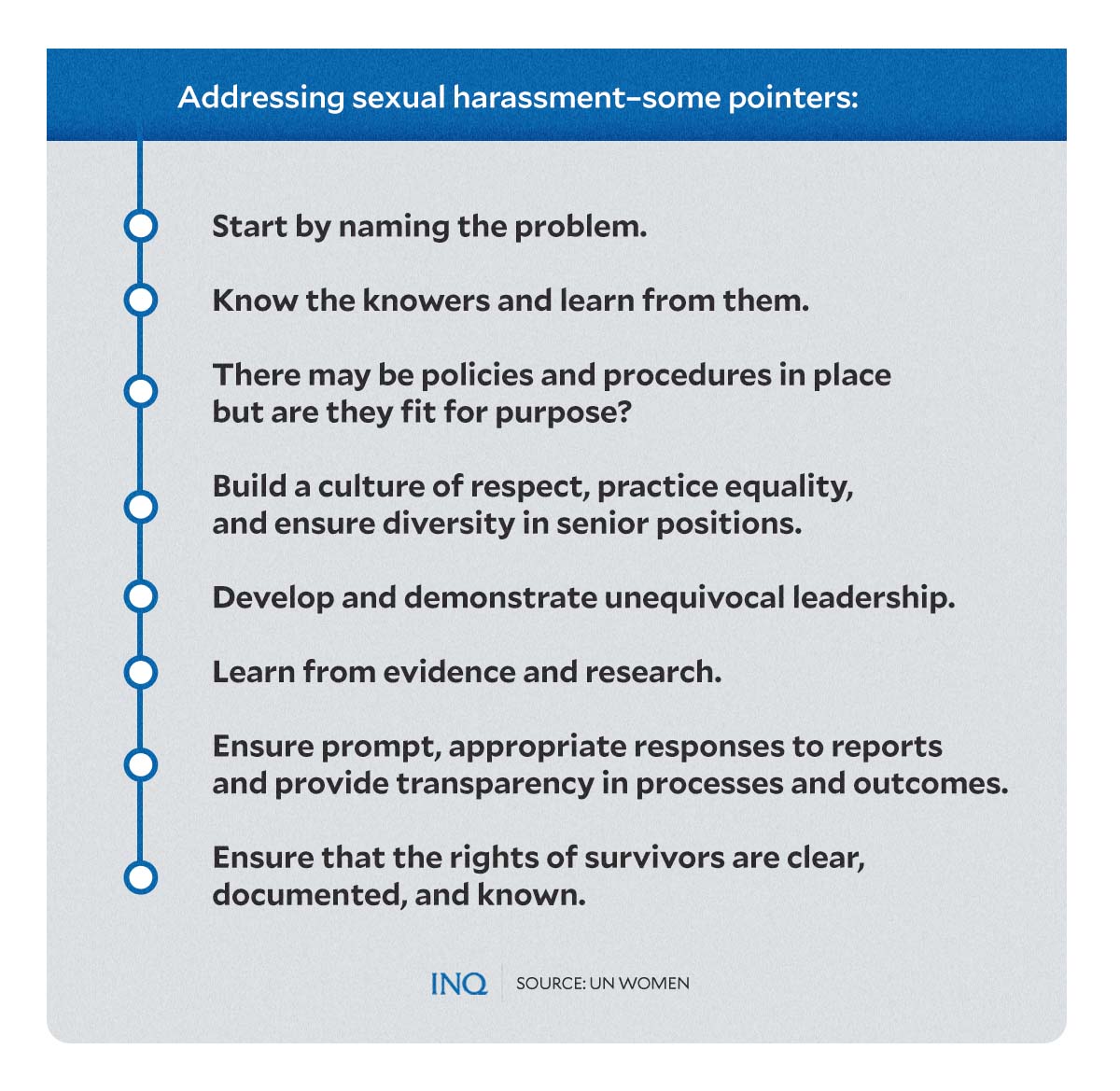

What should be done?

The UN Women, in a paper published in 2018, identified some pointers on addressing sexual harassment. These were:

- Start by naming the problem.

- Know the knowers and learn from them.

- There may be policies and procedures in place but are they fit for purpose?

- Build a culture of respect, practice equality, and ensure diversity in senior positions.

- Develop and demonstrate unequivocal leadership.

- Learn from evidence and research.

- Ensure prompt, appropriate responses to reports and provide transparency in processes and outcomes.

- Ensure that the rights of survivors are clear, documented, and known.

Analysis of the narratives submitted by women to the #HealthToo platform has also led to the following points, which detail ways to prevent and respond to SEAH against women health workers:

- Break the cycle through an increased understanding of the pattern and nature of SEAH—as well as the reasons why perpetrators abuse women.

“Governments and employers must be held accountable, bystanders who do not act must also be held accountable and above all, perpetrators must be held accountable and sanctioned,” WGH stressed. - Combat denial and fear attached to reporting SEAH.

- Provide professional support for survivors to mitigate the longer-term impact of untreated trauma.

- Work facilities and policies must explicitly address the safety of women to reduce and eliminate the risk of SEAH of women health workers.

- Serve justice and make sure that action on SEAH complaints is dealt with in a timely manner.

“Survivors can be exhausted and re-traumatized by very lengthy disciplinary processes and they may drop charges. Justice is then not done and perpetrators may continue abusing women,” WGH noted. - Count the serious physical, mental, personal and economic costs for women health workers of SEAH, including the cost of inaction.

“Shame and blame may fall upon female survivors if the story does surface but as seen from #HealthToo, very often the story does not surface so perpetrators and employers can deny SEAH is a problem,” the organization said.

“Women in Global Health, with our global network of chapters and partners, will continue to raise SEAH of women health workers until all women in the health sector have safe and decent work.”