Marcos offers reconciliation; critics demand atonement

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES | The nation marks the ouster of dictator Ferdinand Marcos 37 years ago with a low-key official government ceremony at the People Power Monument in Quezon City where his son, the president, offered a wreath of white flowers with no message attached. (Photo by LYN RILLON / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

MANILA, Philippines — After recently telling an international audience that he ran for public office to protect his family, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. offered a “hand of reconciliation” to his critics and opponents on Saturday as the country marked the 37th anniversary of the Edsa People Power Revolution that toppled his late father’s dictatorship.

“I am one with the nation in remembering those times of tribulation and how we came out of them united and stronger as a nation,” he said in a statement.

“I once again offer my hand of reconciliation to those with different political persuasions to come together as one in forging a better society — one that will pursue progress and peace and a better life for all Filipinos,” he added.

It was the first commemoration of the Edsa uprising since Marcos took office as president last year.

Groups that fought against his father’s martial rule quickly responded, saying that his statement must come with truth and genuine atonement for the atrocities and the plunder of the nation’s coffers when his family was in power.

Article continues after this advertisement“As we look back at this fateful moment in our country’s history, we remind ourselves that despite the polarizing and divisive nature of our politics, it is our capacity for peace, unity and reconciliation that made us great and worthy of global acclaim as a people,” Marcos said.

Article continues after this advertisementFilipinos, he said, must learn to settle differences and identify collaborative ways to nurture their society.

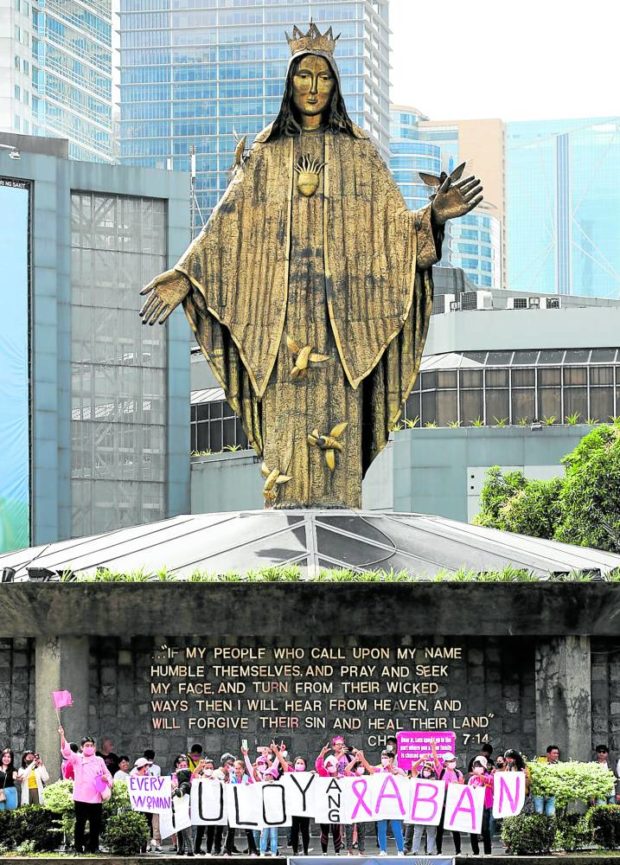

Not far, at the Edsa Shrine, activist groups some in pink shirts held up placards saying “Tuloy ang Laban” (The Struggle Continues). (Photo by LYN RILLON / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

There must be admission

“I hope that we will always take to heart that democracy is only truly possible when we resign from our individualism for the sake of the common good and embrace our infinite love for humanity,” Marcos said.

Liberal Party president and Albay Rep. Edcel Lagman welcomed the president’s statement but said there should be an admission of the horrors committed during his father’s iron rule.

“We welcome the offer of reconciliation by the President, but there must first be an admission of the inordinate atrocities and rampant human rights violations during the dark age of martial law. Truth and atonement are conditions precedent to reconciliation,” he said in a statement to the Inquirer.

A human rights lawyer before becoming a politician, Lagman had a younger brother — Hermon, a political activist — who was a victim of enforced disappearance about five years after the dictator declared martial law in September 1972 and has been missing since.

Kabataan Rep. Raoul Danniel Manuel pointed out that the Edsa revolution was a demonstration of the people’s unity “against corruption and fascism.”

He said that if there was a division during the dictatorship it was between the Marcos family and their cronies on one hand and the “patriotic, peace and democracy-loving Filipino people on the other hand.”

“There will be no reconciliation as long as the Marcos family continues to deny their crimes and refuse to apologize; distort history and spread false versions; fail to pay taxes correctly and hold on to remaining ill-gotten wealth,” Manuel said.

House Deputy Minority Leader Rep. France Castro said that Marcos should prove his sincerity in seeking reconciliation by ensuring that justice is served to victims of human rights violations and that the ill-gotten wealth stolen from the Filipino people is returned.

Sorry, but . . .

She said that peace negotiations to end the 54-year-old insurgency that started during the old Marcos regime should also be resumed and that “efforts to revise our history are stopped.”

“Rhetoric won’t matter if there is no act of repentance for the sins of the Marcos regime,” Castro said.

In an interview in August 2015 with ANC, Marcos avoided making a direct response to a question on whether he would apologize for the atrocities committed during his father’s administration.

“If I had hurt anyone, I will always say sorry, but what I’ve been guilty of to apologize about?” he said.

Separate programs

Marcos added that “if during that time of my father there were those who were hit or not given assistance, or they were victimized in some way or another, of course we’re sorry that that happened. Nobody wants that to have happened.”

At the World Economic Forum in January in Switzerland, he told his audience he wanted to protect his family by going into politics.

“For us to defend ourselves politically, somebody had to enter politics and be in the political arena so that at least, not only the legacy of my father but even our own survival required that somebody go into politics,” Marcos said.

The government’s commemoration was capped by the popping of red, white, and blue confetti and the release of doves as symbols of peace. In previous years, yellow confetti fell on the crowd, the color associated with the late President Corazon Aquino, who succeeded the dictator.

After the official ceremonies, various groups led by the Campaign Against the Return of the Marcoses and Martial Law (Carmma) and Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (Bayan) held their own commemoration program.

Former Bayan Muna Rep. Satur Ocampo, the chief negotiator for the National Democratic Front of the Philippines during the first round of talks under Aquino, said “real unity” among Filipinos was the key to preventing a repeat of the atrocities during the dictatorship.

Ocampo was heavily tortured by the military following his arrest in 1976.

He said the country was now in “our Phase 2 with the Marcoses,” referring to the president and the resurgence of the late dictator’s family in the political arena.

“This is a brewing dictatorship,” Ocampo said, “and we see [Marcos’] policy looking like his father’s, in making alliances with imperialist countries and the ruling class like during the dictatorship.”

‘Bottom line’

About 1,500 people attended the rally, including many who took to the streets in protest against the dictatorship before and during the Edsa revolt.

Veteran rights activist Sister Mary John Mananzan urged protesters to “remain vigilant” following the return of the Marcoses to power.

Nearly four decades on from the toppling of the dictator, Julio Montinola, 53, told French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP) that the challenge was to keep the “message and spirit” of the uprising alive.

“Unfortunately, it did not resonate with the next generation,” said Montinola. “The bottom line is he (Marcos) was elected by the people.”

As the ailing strongman desperately clung to power, hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets of the capital for four days in the military-backed uprising against his regime.

The family and their close associates fled Malacañang on Feb. 25, 1986, on a US military aircraft with bags and boxes stuffed with jewels, gold, and cash.

After the ousted dictator died in Hawaii in 1989, the family returned to the country, rebuilt their political power base, and started to rehabilitate their name.

Their efforts culminated with the president’s victory last year, aided by a massive social media misinformation campaign to whitewash the family’s history.

Cristina Palabay of human rights alliance Karapatan fears the Marcos clan is still determined to cleanse their name and hold on to their ill-gotten wealth, which is estimated to be in the billions of dollars.