Artificial habitats: Not enough to save PH coral system

MANILA, Philippines—As scientists, environmentalists, and experts revive dying coastal communities due to the degradation of coral reefs, a recent policy brief found that deploying artificial habitats (AH)—formerly known as artificial reefs—might not be enough to solve plunging coral cover in the country.

Aside from coral propagation and mangrove reforestation, the deployment of artificial habitats is being used in the country’s waters to mitigate the loss of coral reefs—caused by decades of illegal fishing—and improve the catch of coastal fishers.

Artificial habitats are man-made structures—usually of concrete, limestone, or rocks—that are placed on the sea bed to serve as shelter and habitat, source of food, and breeding areas for fishes and other marine organisms.

According to a policy brief titled “Deployment of Artificial Habitats Alone Cannot Make up for the Degradation of Coral Reefs,” published in The Philippine Journal of Fisheries, artificial habitats could also serve as “firm substrates for coral growth.”

However, the policy brief—which applied lessons learned from a project led by the DLSU Shields Ocean Research (SHORE) Center—stressed that the deployment of artificial habitats should not be treated as a “‘magic bullet to stop depletion and degradation of Philippine coastal resources.”

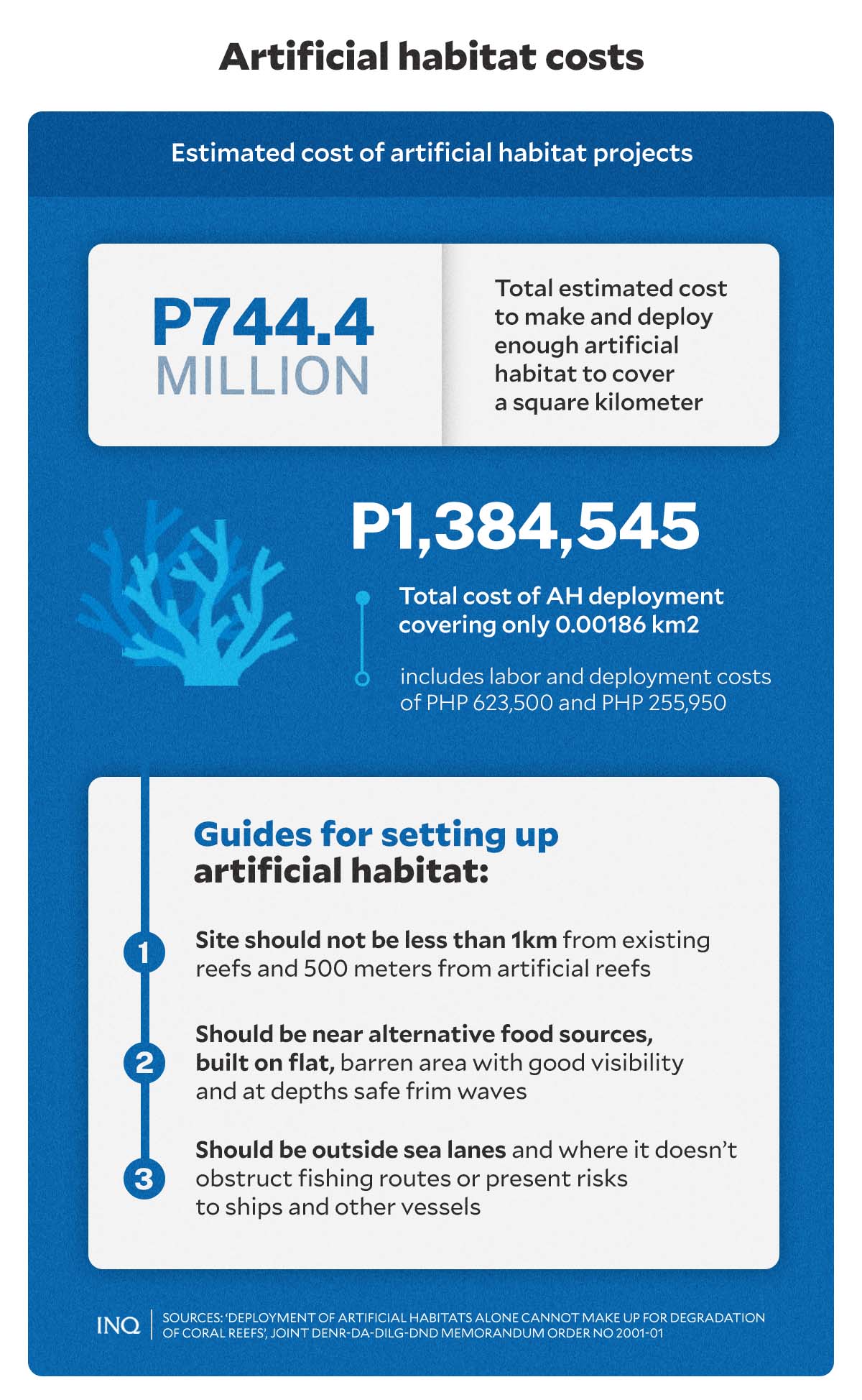

“Artificial habitat projects are expensive endeavors that should be carefully designed and planned to be sustainable and effective,” the scientists, who authored the policy brief, wrote.

Deploying AH: Not enough

The policy brief carried findings from the DLSU SHORE Center’s project, which observed the deployment of different artificial habitat modules—like open-frame cube, truncated pyramid, and jackstone modules—“to evaluate their suitability for enhancing coral settlement and fish recruitment.”

The lessons learned from the project were then applied by the scientists who authored the policy brief to come up with recommendations for improving the Joint DENR-DA-DILG-DND Memorandum Order No. 2000-01—a memorandum order issued to provide policy guidelines on the establishment, utilization, and management of artificial habitats.

Section 11 of the joint memorandum order stressed that the management and deployment of artificial habitats, as part of broader coastal protection and conservation efforts, is the primary responsibility of the cooperative, organization, or association which should abide by a list of measures and fisheries regulation.

However, the policy brief noted that relying on artificial habitats alone to address the loss of coral reefs in the country’s coastal communities would be restrictive, considering the “considerable cost and massive effort involved in covering a small area with [artificial habitats].”

The Philippines’ coral reef system is the second largest in Southeast Asia, with corals that cover 240 million hectares of water. It serves as home to 468 species of scleractinian corals, 50 soft corals, 1,755 reef-associated fishes, and 648 mollusks.

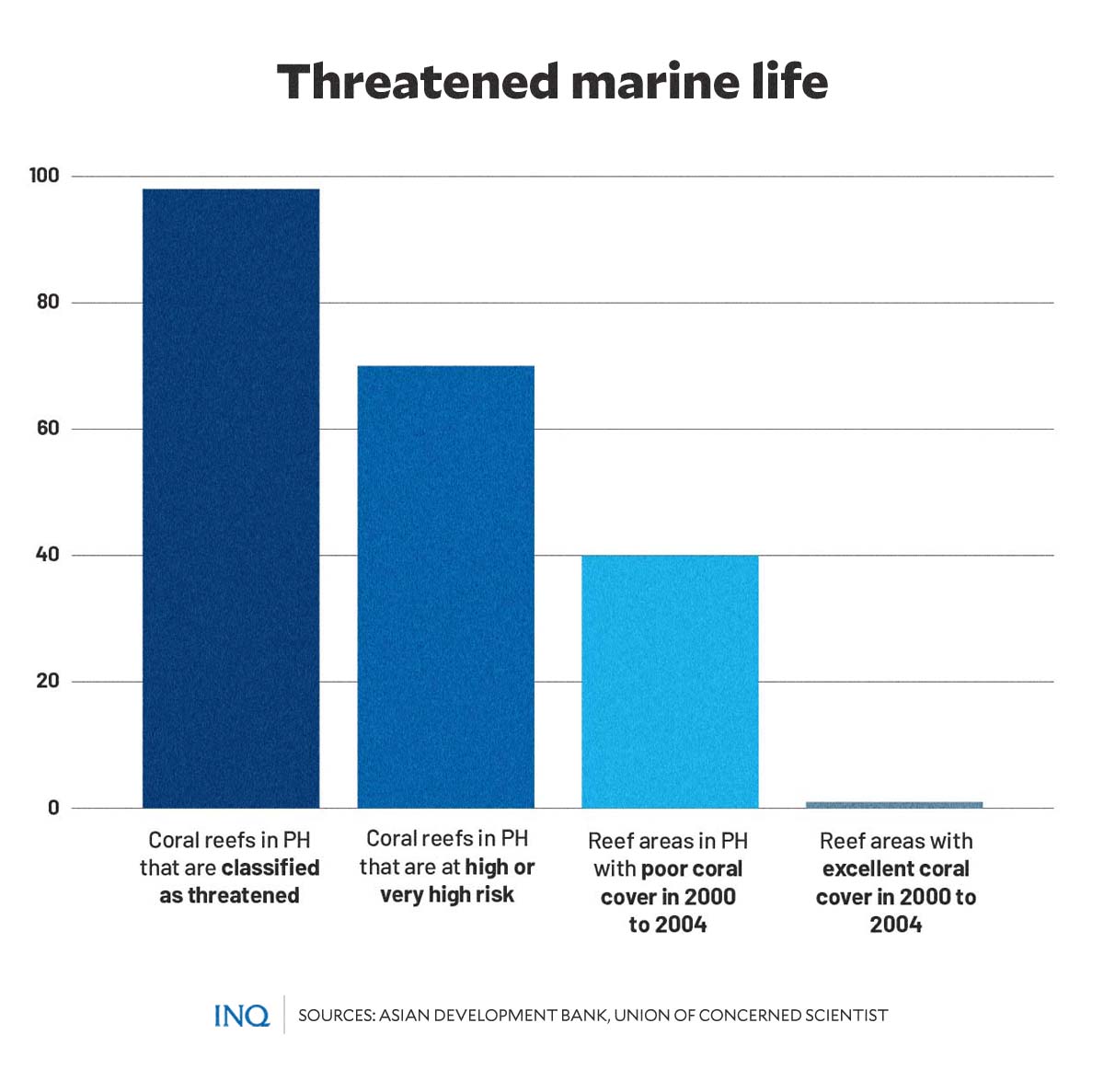

Data from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), however, showed that reef areas with poor coral cover accounted for 40 percent of world total from 2000 to 2004. Conversely, reef areas with excellent coral cover comprised less than one percent.

The Union of Concerned Scientists added that some 98 percent of coral reefs in the Philippines was classified as threatened, with 70 percent at high or very high risk.

READ: Dying Masbate marine ecosystem revived as PhilGold deploys thousands of reef balls

The policy brief also explained that the deployment of artificial habitats is justified only in a few situations, which include tourist dive spots in isolated regions, deterring the use of nets, and serving as submerged breakwaters to protect shorelines.

On crucial AH site selection

Under Section 9 of the joint memorandum, the criteria for the site selection of the artificial habitats were:

- the site where the artificial habitats will be installed should not be less than 1 kilometer away from existing natural reefs if any, and 500 meters away from existing artificial habitats

- artificial habitats should be deployed near alternative food sources—such as seagrass beds—and must be constructed on a flat, barren area of relatively good visibility and at depth protected from wave action but still accessible (around 15-25 meters)

- the artificial habitats should be installed outside designated navigational sea lanes and do not obstruct the traditional navigational route of local fishermen going to and from the fishing ground or pose as a navigational hazard to ships and other sea crafts.

The policy brief, on the other hand, suggested updating the section of the joint memorandum and including a site selection requirement.

According to the scientists, this will “ensure that the environmental and ecological features of the target site are considered for the proper structural design and construction of [artificial habitat] before starting any project.”

The scientists also listed some revisions from the criteria mentioned in Section 9 of the joint memorandum, such as:

- instead of installing artificial habitats at depths of 15-25 meters, a depth of 5-10 meters is deep enough to avoid large waves but shallow enough to allow for monitoring without scuba

- the site where the artificial habitats will be installed should be more than 1 kilometer away from natural reefs to avoid attracting fish and depleting reef stocks and 500 meters from existing artificial habitats.

They also listed additional criteria to be considered when choosing the site of artificial habitats, which include:

- artificial habitats should be deployed on broad areas of the reef but not on the reef flat, which is the shallow part of the reef exposed during low tides

- the bottom composition of the site of deployment must be composed of compact sand and rubble instead of silty bottoms to prevent the artificial habitats from getting buried

- the site of deployment must also be far from rivers and streams to avoid high sedimentation levels that negatively influence corals and fish.

AH: Not as cost-effective

Artificial habitats have also been found to cover only small areas yet rehabilitation efforts using these would cost more than implementing a management plan that could help protect a broader marine area.

According to the policy brief, the total cost of deployment of three different concrete artificial habitats used in the project by the DLSU SHORE center was P1,384,545. These include:

- P505,095 for the materials used for the artificial habitat modules, which covered only 0.00186 square kilometers;

- P623,500 for labor costs

- P255,950 for the deployment costs.

This means that P744.4 million is needed to make and deploy enough artificial habitat to cover a square kilometer.

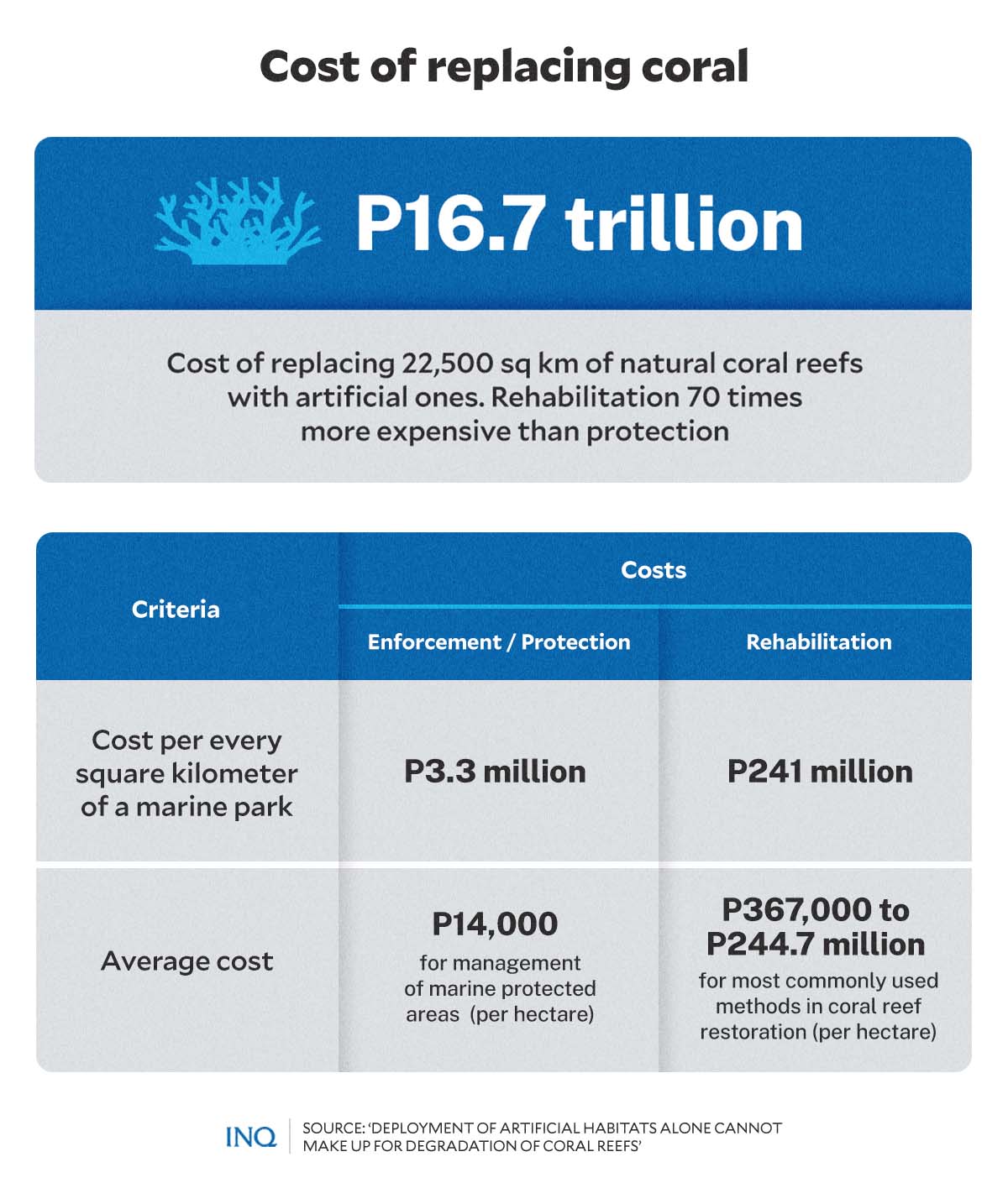

This roughly translates to at least P16.7 trillion in cost to replace around 22,500 square kilometers of natural coral reefs with artificial versions, “assuming there are enough suitable places for all this concrete to be deployed in the sea.”

On the other hand, previous studies showed that it costs around P1 million to adequately manage a square kilometer of a marine protected area.

From 2000 to 2005, the Tubbataha Management Office—which oversees 970.3 square kilometers of the largest and best-managed marine protected area in the country—spent around P10 million to implement a management plan, or around P10,306 to protect a square kilometer area.

The policy brief, citing another study, added that enforcement would only shell out about P3.3 million for every square kilometer of a marine park. In comparison, rehabilitating the same area would cost P241 million.

The estimated cost of the most commonly used methods in coral reef restoration range from about P367,000 to 244.7 million per hectare. The cost of establishment and management of marine protected areas averages about P14,000 per hectare.

“These computations show that rehabilitation is approximately 70 times more expensive than protection,” the policy brief stated.

“[T]he protection and conservation of reefs by eliminating the anthropogenic stressors and allowing natural coral recovery appear far more cost-effective than restoration efforts like artificial habitats,” it added.

Consistent, regular monitoring needed

Section 12 of the joint memorandum requires annual monitoring of the socio-economic benefits and the ecological impacts of the deployment of artificial habitats.

It also requires the Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) and regional offices of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to gather baseline data on initial recruitment, standing stock, and other relevant scientific information and observations six months following the installation of the artificial habitats.

However, the policy brief noted that the annual socio-economic evaluations of artificial habitats—which the scientists said are rarely done—is not enough. Instead, the scientists suggested consistent monitoring.

“Data gathered from regular monitoring would be helpful for the improvement and development of both current and future projects,” the scientists who wrote the policy brief explained.

“Given the expenses needed for monitoring, this reinforces the recommended requirement that [artificial habitat] deployments must always be part of a broader management plan to be more sustainable and cost-effective.”