Child labor: The monster remains a threat in PH, worldwide

MANILA, Philippines—The fight against child labor has seen global progress in the past years. However, it remains to be a major challenge in many parts of the world as new data showed a rising number of children being forced into mostly hazardous work.

Child labor, as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO), is “work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential, and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development.“

These include work that is:

- mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous and harmful to children

- interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school

- obliges them to leave school prematurely

- requires them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work.

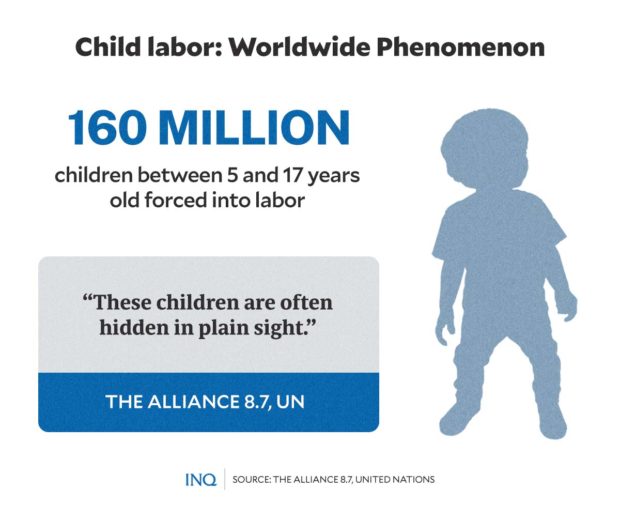

Data by Alliance 8.7—a global partnership for eradicating forced labor, modern slavery, human trafficking and child labor around the world—showed that across the globe, there are 160 million—or 1 in 10—children aged 5 to 17 engaged in child labor in 2020.

The good news, according to Alliance 8.7, is that between 2016 and 2020, there has been significant progress in addressing and reducing the number of children entering the workforce at a very early age.

Article continues after this advertisementProgress so far

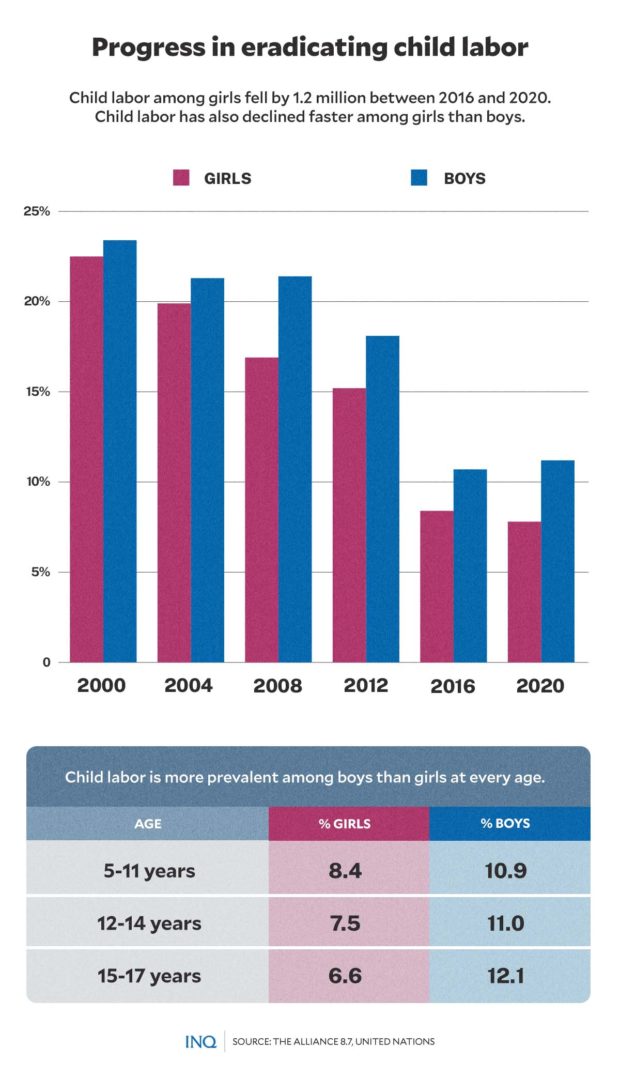

Alliance 8.7 noted that between 2016 and 2020, child labor among girls went down to 1.2 million cases. From 8.4 percent recorded in 2016, the share of young girls in child labor slipped to 7.8 percent in 2020.

Article continues after this advertisementChild labor among boys slightly rose from 10.7 percent in 2016 to 11.2 percent in 2020. The data likewise showed that child labor has been more prevalent among boys than girls at every age.

Figures also showed that since 2000, cases of child labor had declined faster among girls than boys.

However, while Alliance 8.7 acknowledged that the numbers represent a “success story,” it explained that it does not present the full picture.

“Many girls engage in caregiving, cooking, and other domestic chores for long hours that interfere with their schooling. But the definition of child labour does not include such work–if it did, many more girls would be classified as child labourers,” it added.

Alliance 8.7 said child labor among those aged 12 to 14 years olds fell from 49.1 million cases in 2016 to 35.6 million in 2020.

However, the organization also saw “a worrying rise in child labor among very young children” or those who are just 5 to 11 years old. From 8.3 percent in 2016, the share of 5 to 11 year-old children forced to work rose to 9.7 percent in 2020.

Global progress stagnated

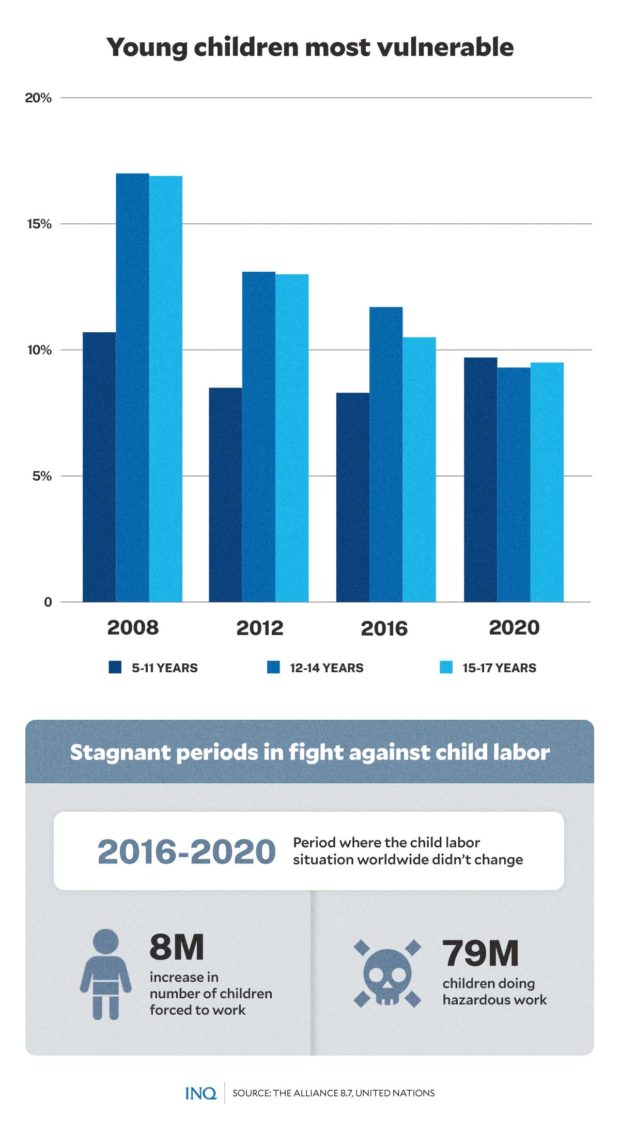

Global progress in the fight against child labor, however, stagnated from 2016 to 2020.

According to Alliance 8.7, over the four year period, the percentage of children in child labor around the globe remained unchanged while the absolute number of children forced to work went up by over 8 million.

From 151.6 million in 2016, the number of children in child labor rose to 160 million.

“This result is alarming. Global progress against child labour has stalled for the first time since the ILO began tracking it, two decades ago. Without urgent measures, the COVID-19 crisis is likely to push millions more children into child labour,” Alliance 8.7 said.

“This is our reality check. We have a global commitment to end child labour by 2025. If we do not act now on an unprecedented scale, the timeline for ending child labour will stretch years further into the future,” it added.

Nearly half of children forced to work in 2020—around 79 million—are doing so in hazardous conditions which directly endanger their health, safety, or moral development. The figure increased from 72.5 million in 2016.

“Hazardous work has persisted and expanded among younger children. This is particularly concerning, considering the common hazards that children are exposed to include harmful agrochemicals, physically strenuous tasks such as carrying heavy loads, exposure to extreme temperatures, use of dangerous tools, and worse,” said Alliance 8.7.

Child labor in PH

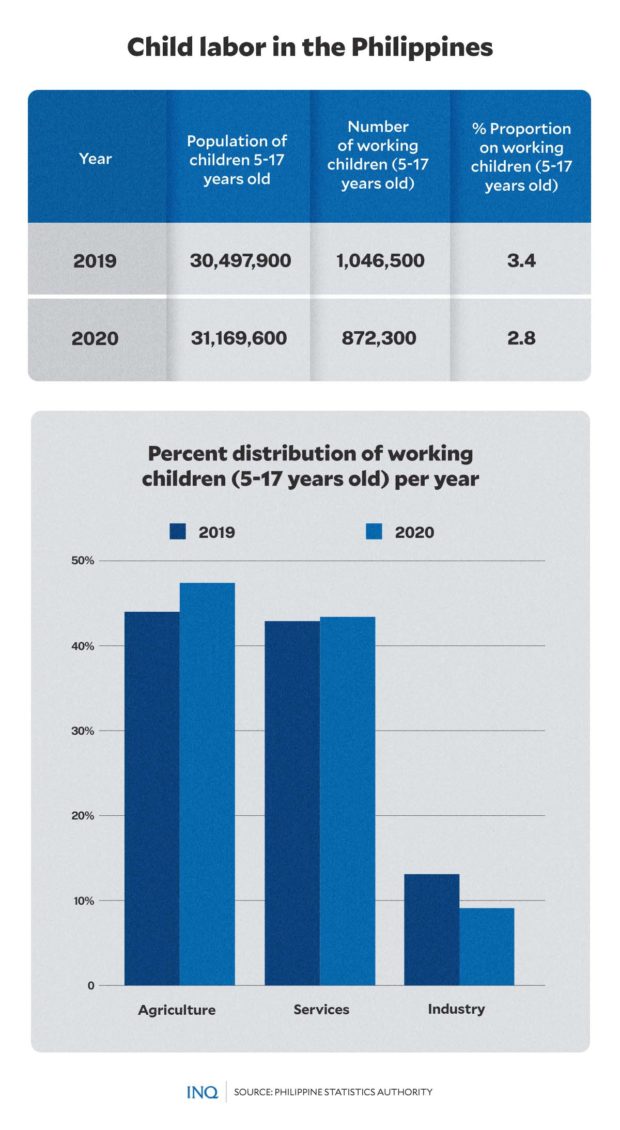

In the Philippines, as of 2020, there were 872,300 children aged 5 to 17 years old in child labor—or 2.8 percent of the age group’s total population, pegged at around 31,169,600, according to data released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

The figures slid from 1,046,500 children aged 5 to 17 in child labor recorded in 2019—or 3.4 percent of the total 30,497,900 children in the same age group that same year.

The PSA also noted that children belonging to the older age groups (5 to 17 years) were more likely to work than the younger ones. Majority of working children belonged to the age group 15 to 17 years of age, accounting for 68.9 percent of the total working children in 2020 and 67.4 percent in 2019.

In 2020, the sector with the highest number of working children was agriculture—accounting for 43.4 percent of the total number of working children that year. It was followed by the services sector with 43.4 percent, and industry sector with 9.1 percent.

The proportion of children (5 to 17 years of age) engaged in hazardous work and long working hours, according to the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) administrative order, shot up from 61.2 percent in 2019 to 68.4 percent in 2020.

Unicef had expressed concern about the child labor situation in the Philippines, noting that millions of Filipino children might be pushed to work as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.

“As the pandemic wreaks havoc on family incomes, without support, many could resort to child labour,” ILO Director-General Guy Ryder previously said.

“Social protection is vital in times of crisis, as it provides assistance to those who are most vulnerable. Integrating child labour concerns across broader policies for education, social protection, justice, labour markets, and international human and labour rights makes a critical difference,” he added.

COVID-19, Unicef noted, could result in a rise in poverty and, therefore, an increase in child labor as households use every available means to survive.

“In times of crisis, child labour becomes a coping mechanism for many families,” said former Unicef Executive Director Henrietta Fore.

“As poverty rises, schools close and the availability of social services decreases, more children are pushed into the workforce. As we reimagine the world post-COVID, we need to make sure that children and their families have the tools they need to weather similar storms in the future. Quality education, social protection services and better economic opportunities can be game changers.”

Strengthening fight against child labor

Alliance 8.7 believes that without proper mitigation measures, an estimated 8.9 million more children will “likely be engaged in child labour by the end of 2022 due to the poverty impacts of the COVID-19 crisis.”

“Without accelerated action, we will not come close to our goal of eliminating child labour by 2030. Projections based on trends predict a mere 22% reduction in child labour over the next eight years,” it added.

To help reduce child labor worldwide and prevent the projected increase in the number of children engaged in hazardous work, Alliance 8.7 said policies that promote social protection programs would be crucial.

These include policies on improving access to health care and income security, as well as policies that promote decent work and gender equality.

In the Philippines, several laws are in place to protect the safety and welfare of children, including:

- Presidential Decree (P.D.) 442 Labor Code of the Philippines

- P.D. 603, The Child and Youth Welfare Code

- Republic Act (RA) 9231 or an Act Providing for the Elimination of the

- Worst Forms of Child Labor and Affording Stronger Protection for the

- Working Child, which amended RA No. 7610

- R.A. 9775, or Anti-Child Pornography Act

- R.A. 10361, or Domestic Workers Act

- R.A. 10364, or the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2012 that included as acts of trafficking the worst forms of child labor defined in

- Republic Act No. 9231

- R.A. 10821, or the Children’s Emergency Relief and Protection Act.

Last October, the Quezon City government also formed “Task Force Sapaguita” to protect children in the city from forced labor and abuse, following the increase in the number of minors selling sampaguita garlands in the city.

Task Force Sampaguita is currently helping profiled families by way of livelihood assistance, educational assistance, and more.

READ: QC gov’t forms task force against child labor, abuse

Last June, DOLE reported that over 90,000 children have already been removed from doing harmful work since the department started profiling child laborers—as part of the Philippine Development Plan 2017–2022 goal of reducing child labor cases by 30 percent.