In Pangasinan, ‘love affair’ with native trees blooms

EVERGREEN | Some 300 species of native trees grow in harmony on a tree farm established more than 20 years ago by former Environment Secretary Victor Ramos. The mini forest in Natividad town, Pangasinan province, according to Ramos, is a realization of a childhood dream. —(Photo by WILLIE LOMIBAO / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

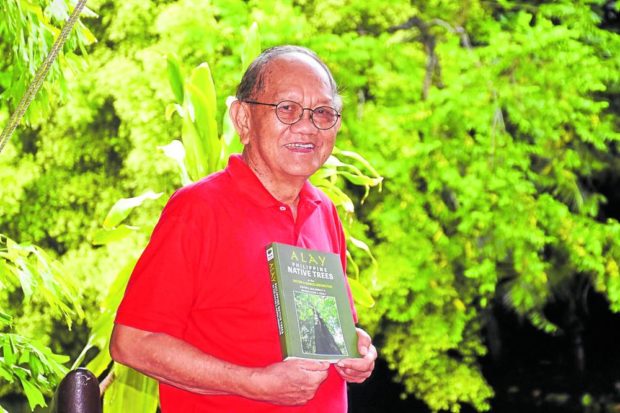

NATIVIDAD, Pangasinan, Philippines — Growing up in a farming town in the shadow of the Cordillera mountains, former Environment Secretary Victor Ramos recalls how children like him were awed by trees that they would climb for their fruits.

During those days, “reverence for trees came naturally for boys like me,” Ramos tells the Inquirer.

“We showed respect to the trees by asking permission to pass by quietly. We were both awed and terrified of some trees that provide havens for some imagined ghosts,” he says.

According to him, schoolchildren then would observe the periodic blooming of some trees to know if it was already close to the end of the school year.

“Nature was a daily part of our upbringing,” he says.

Article continues after this advertisementThe former head of a department tasked with protecting the country’s trees, forests and natural resources reminisces about his childhood while sipping coffee on the porch of a wooden house in the middle of a 4-hectare property in Natividad town, which is next to San Nicolas town where he grew up.

Article continues after this advertisementThe property is a mini forest of some 300 native trees, which are either indigenous or endemic to the Philippines. Indigenous species are native to a place but can also be found in other places, while endemic to a place means a species can only be found in a particular area, Ramos explains.

The arboretum (botanical garden devoted to trees) is tucked behind an elementary school and accessible by a bridge across a street canal.

There is nothing extraordinary at the property’s entrance, nor is there a signboard to announce what to expect around the corner.

But the gate opens to a seemingly different world: a pebbled road canopied by towering trees, a hectare-wide man-made pond, a bridge adorned with flowering plants, a house made of wood, a sprawling lawn and greenery all over.

“Exhilarating” may be an understatement when describing a visit to the arboretum, Ramos says.

A visitor can easily feel that it’s cooler at the property, with the temperature about 2 degrees Celsius lower than the prevailing reading. The arboretum is also an open classroom where one can learn anything about native trees (some of them common, others rare, and a few almost extinct) like how tall they can grow, how hard their wood is and their medicinal properties. Basic facts like the trees’ local, common and scientific names are provided in labels below each species.

The arboretum is also an open classroom where one can learn anything about native trees. (Photo by WILLIE LOMIBAO / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

Childhood dream

Ramos believes that the tree farm, named Victor O. Ramos Arboretum, is a realization of his childhood dream to retire in “quiet place with a lot of trees.”

Everything seems to fall into place for Ramos, who, after leaving the corporate world, went on to head the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) from 1995 to 1998 under the administration of the late President Fidel V. Ramos.

While at the department’s helm, Ramos’ innate love for trees surfaced when he initiated the shift in policy from pro-logging to community-based stewardship of the country’s forest lands.

He also then denied the issuance of an environmental compliance certificate to the proposed multimillion-dollar cement plant complex in Bolinao, Pangasinan, citing the environmental degradation it would create.

“The department then was too focused on commercial timber trees because of the need for lumber. I got to know more about native trees after my time in the DENR. That happened when I joined like-minded enthusiasts for native trees,” he says.

Ramos started the arboretum when he turned 50, before he joined the government. He asked friends and well-wishers to gift him with saplings, and, as expected, he received seedlings like those of golden coconuts and golden showers, mahogany and acacia.

But his “love affair” with Philippine native trees came after his stint as environment secretary when he had more time to focus on propagating them.

The then empty land in Natividad was planted with the saplings which became “nurse trees” for the native tree seedlings Ramos later acquired from the University of the Philippines (UP) Los Baños in Laguna province.

“My first native tree saplings were yakal, bagtikan, guijo, kalantas, saplungan, malibato and narig,” recalls Ramos, now 77.

WATER FEATURE | A hectare of pond carved out of Ramos’ 4-hectare arboretum contains water from springs and sustains the native trees at the property all year round. (Photo by WILLIE LOMIBAO / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

‘Keepers of stories’

Ramos hopes that the younger generation will develop a passion for propagating native trees, some of which are disappearing because of deforestation.

“The rich biodiversity of our trees and plants is the foundation of human life as we know it. Losing them is a tipping point toward disasters, as history keeps reminding us,” he says.

Some civilizations, like that of the Mayans, collapsed because they lost their trees, which resulted in the loss of water and the capacity of the place to produce food, Ramos notes.

Trees, he says, are keepers of stories of “how our early ancestors lived their lives, which trees they depended on for food, what cured their ailments, what provided oil to light their living spaces or helped them catch more fish in the rivers.”

“These lessons become more important as we confront the challenge of living on a fast-changing planet, causing life-threatening events like droughts, heat waves and flooding,” he adds.

Ramos willingly shares tidbits about how the trees he accumulated through the years preserve their kind.

“When some trees, such as langka (jackfruit), die, their last fruit will be under the soil, where the seeds will germinate and ensure that the species will not be extinct,” he says.

He adds: “When molaves are in full bloom, there could be a long drought in the offing. Threatened trees release flowers and seeds, which are also nature’s way of preserving the species. “

PRACTICAL GUIDE | The book “Alay” gives readers a crash course on Philippine trees. (Photo by YOLANDA SOTELO / Inquirer Northern Mindanao)

Lessons

There are many more “tree lessons” from Ramos, which he learned through his years of bonding with native trees.

A book that features 250 available native trees on the farm was published by the Philippine Native Tree Enthusiasts (PNTE).

The book, “Alay: Philippine Native Trees at the Victor O. Ramos Arboretum,” is authored by Pastor Malabrigo Jr. and Arthur Glenn Umali, professor and assistant professor, respectively, of the College of Forestry and Natural Resources at UP Los Baños.

Each tree gets a page listing its local and scientific names; the places where it can be found; and uses of its trunks (timber for building boats, houses, furniture, musical instruments and others), leaves and flowers. Most trees have medicinal properties, and the book is a good source of information about medicinal plants.

PNTE founder Arceli Tungol says the 322-page book “covers a significant volume in a sector that has seen very limited coverage regarding one of our most precious but often ignored resources—our Philippine native trees.”

“PNTE will strive to bring the book to the general public as well, in the hopes that knowledge of these trees will spark new interest that will motivate more people to support our advocacy,” Tungol adds.

RELATED STORIES

Contested mini forest in Baguio to be turned into park

Gov’t not monitoring ecosystems in mining reforestation, says expert

Masungi exec to DENR: We reforest amid danger, yet you question our contract?