‘Move on’: The shallowness of calls to bury martial law memories

FILE PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines—Move on.

To people in a relationship, those words could mean letting go of a partner after years of abuse. It could mean a new partner, a new relationship or a new life. The scars left by the abuse, however, won’t disappear.

Applied to an entire nation, the proposal to move on carries an entirely different weight especially if it meant forgetting plunder, state murders, abuses of basic rights, state suppression of freedoms or turning a blind eye on people’s sufferings.

Move on. The comment seemed nonchalant, or even shallow, as made by two senators whose knowledge about martial law in the Philippines might have come vicariously. One was just about nine years old when martial law was declared. The other was just two.

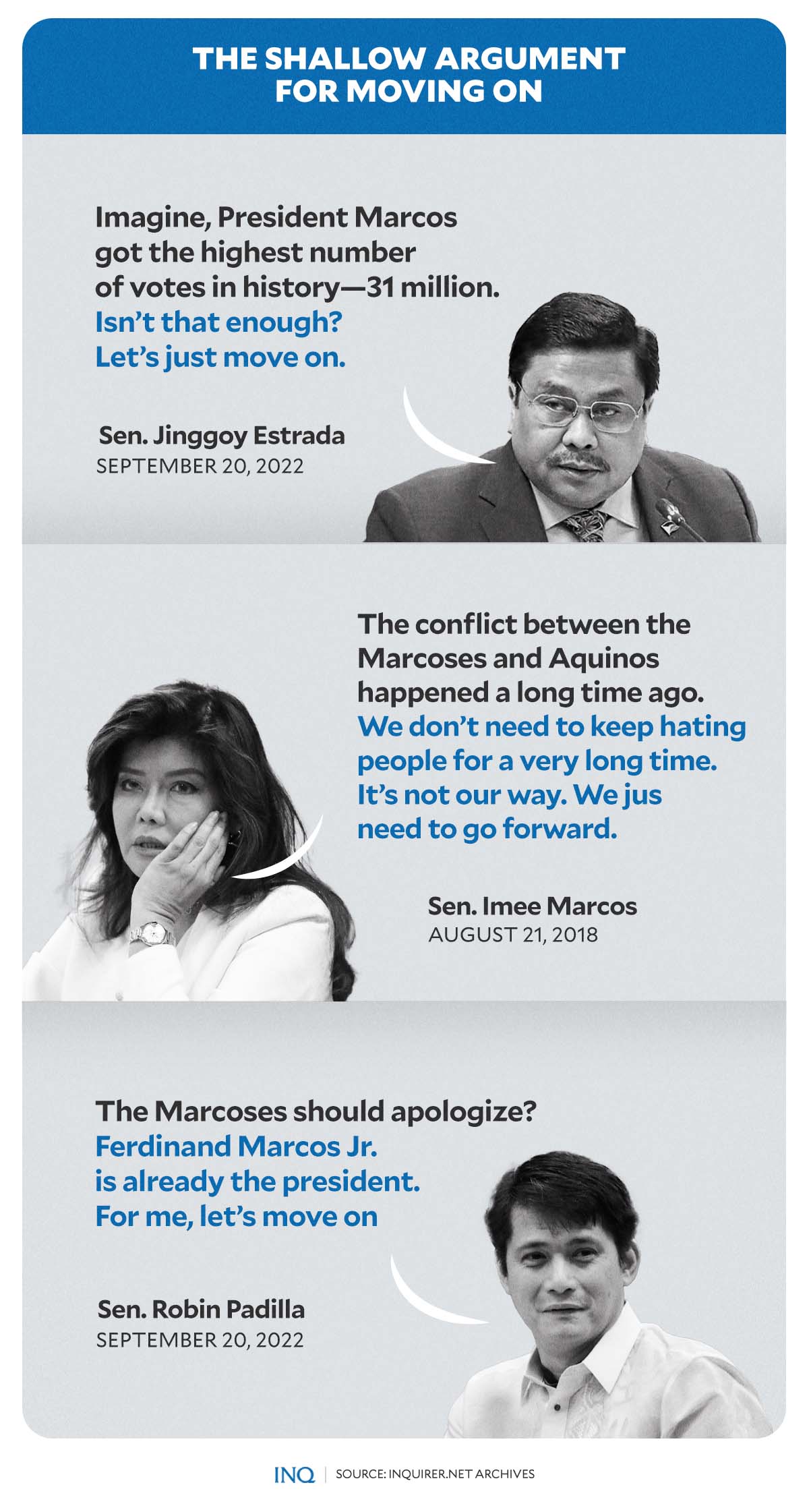

Move on, thus said senators Jinggoy Estrada, 59, and Robin Padilla, 52, when asked for their comments on the 50th anniversary of martial law, the only period in Philippine history when one man—Ferdinand Marcos—reigned for more than 20 years that changed Philippine politics forever.

READ: Estrada, Padilla tell public to ‘move on’ ahead of martial law 50th anniv

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

“What is there to apologize for?” said Estrada. “Let’s move on,” said the senator, whose father actor Joseph Estrada didn’t finish his term as president and was forced out of office by what is now known as People Power 2.

According to Estrada, the strongest argument in favor of the nation moving on from martial law was the 31 million votes that the late dictator’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., had received in elections last May. According to Estrada, this was enough proof that the younger Marcos had nothing to say sorry for.

Padilla, who had his own brushes with the law in the early years of his popularity as an actor, shared Estrada’s view.

He said unless Filipinos let go of the bad memories of martial law, “we would not grow”, equating progress with the process of forgetting what historians said was the darkest chapter of Philippine history following the Second World War.

“The Marcoses should apologize? Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is already the president. For me, let’s move on,” said Padilla, repeating a previous statement about the father’s sins not being his children’s.

While Estrada said that victims of human rights violations during the dictatorship have the right to air grievances, it was actually up to Marcos Jr. to listen to these.

‘We will not move on’

In response to the remarks of Estrada and Padilla, Bayan secretary general Renato Reyes said “only those who benefited and continue to benefit from the events 50 years ago seem to have a liking to ‘moving on’ from the horrors of the dictatorship.”

This, as back in 2018, Sen. Imee Marcos, daughter of the late dictator, said that Filipinos criticizing her family should move on: “We don’t need to keep hating people for a very long time. It’s not our way. We just need to go forward.”

READ: Imee Marcos asks Filipinos criticizing her family: Why don’t you move on?

Maria Ela Atienza, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines Diliman, said that it was wrong to ask Filipinos to move on and forget the horrors of the dictatorship.

“There are still ongoing cases against the Marcoses and the damage they have done to the Philippines, supported by evidence, has not yet been repaired,” she told INQUIRER.net on Wednesday (Sept. 21).

She said Estrada and Padilla make a “mockery of themselves because their words are blatant admission that they are not worthy of being a representative of the people under the 1987 Constitution.”

“Remember that Congress was one of the institutions closed after the declaration of martial law and was replaced by the rubber stamp Batasang Pambansa,” she said.

‘It’s difficult’

Looking back, Joanna Cariño, an indigenous people’s rights activist and a victim of martial law herself, told ANC last May that “it is difficult to move on while there is injustice.”

“Justice has not been served. It is difficult to move on if they have not shown any remorse for the horrors of martial law,” she said.

Marcos Jr. told CNN Philippines last year that “I can only apologize for myself, and I am willing to do that if I have done something wrong and if that neglect or that wrongdoing has been damaging to somebody.”

He was asked then if he will say sorry for the rights violations committed when his father was president for over 20 years, but he said that “no matter what apologies you give, it won’t be enough.”

“It’s not been enough because the political forces opposing my father, let us remember, his government fell. They won. That side of the political aisle has been dominant since 1986,” he said.

Then back in 2018, while Imee said that “for those who got hurt, for those who were inadvertently pained, certainly we apologize,” she stressed that they would never offer an apology that is as good as an admission of the violations committed by the dictatorship.

Dark era

On Sept. 23 50 years ago, Marcos Sr. declared martial law through Proclamation No. 1081. It was officially lifted on Jan. 13, 1981, but he “reserve[d] decree-making powers for himself” until his regime was ended by the 1986 People Power Revolution.

READ: Marcos’ martial law: Golden age for corruption, abuses

In a statement to commemorate the anniversary of the declaration of martial law, political prisoners said “it is written in history and will always be remembered that the imposition of Marcos’ one-man rule and the fascist military machinery on the civilian populace brought about intense suppression and violation of human rights, economic crisis and suffering all through the 11 years of Marcos dictatorial rule until he was ousted through a popular uprising in 1986.”

Based on data from the New York-based Amnesty International, which sent missions to the Philippines in 1971 and 1982, 70,000 people had been imprisoned, 3,257 had been killed and 34,000 had been tortured by state forces during the dictatorship.

The Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearance, meanwhile, said that 878 individuals had been forcibly disappeared.

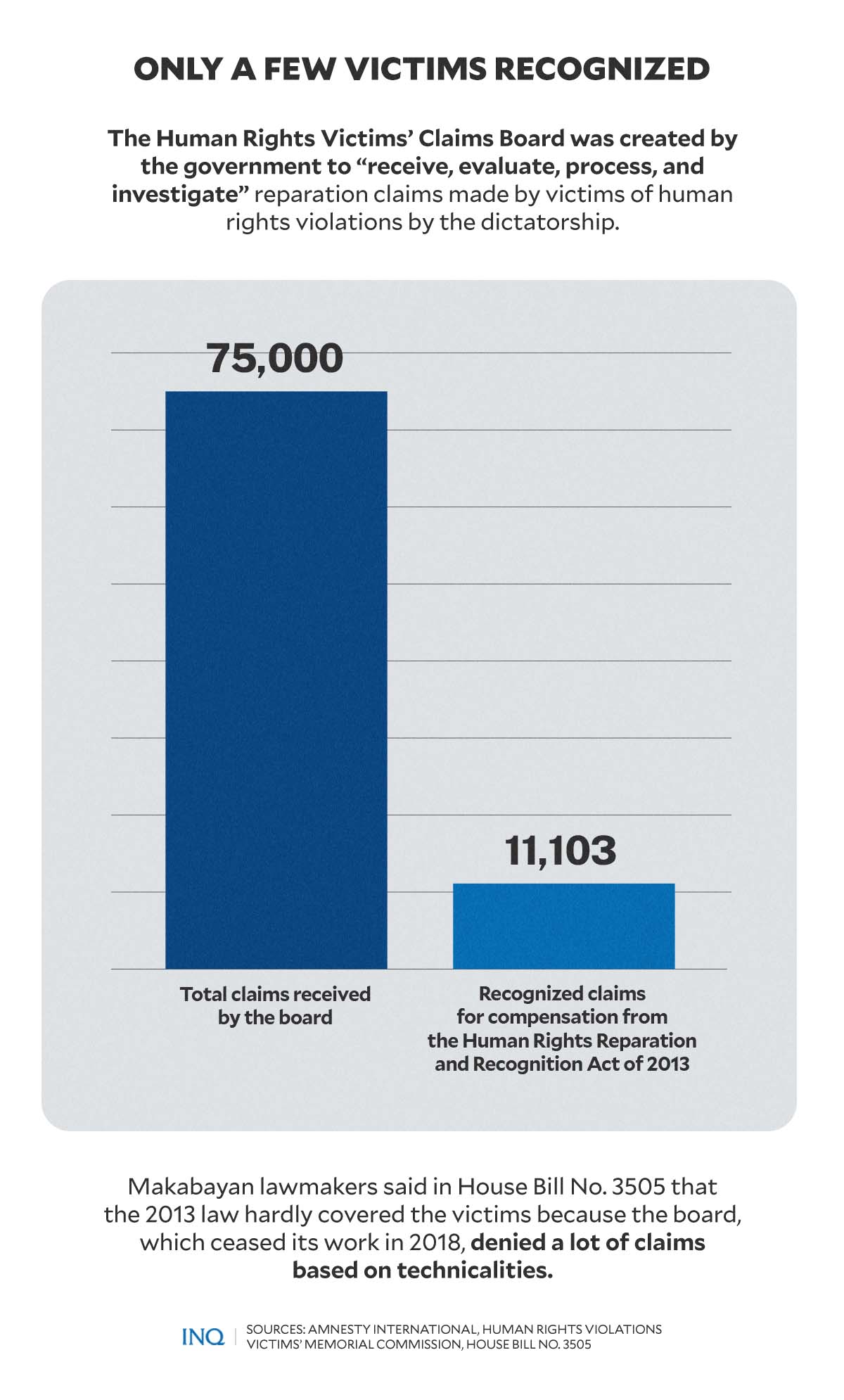

Through the Human Rights Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013, the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board, which ceased its work in 2018, was able to receive 75,000 claims.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

However, Makabayan lawmakers at the House of Representatives said that the 2013 law hardly covered all the victims because the board denied many claims based on technicalities. To date, there are only 11,103 recognized claims.

The Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission stressed that the gross domestic product (GDP) per person fell by 9.4 percent in 1984 and 1985, stressing that so immense was this downturn that it took the Philippines two decades to recover.

This, as in the early 1980s, the Philippines dramatically—but expectedly—fell into its worst postwar recession. GDP shrank by 7.3 percent for two consecutive years—1984 and 1985.

The Martial Law Museum likewise stated that “poverty worsened” over the course of the dictatorship, emphasizing that six out of 10 families were poor by the time the Marcos regime ended, an increase from the four out of 10 families before he took office in 1965.

Paying debt

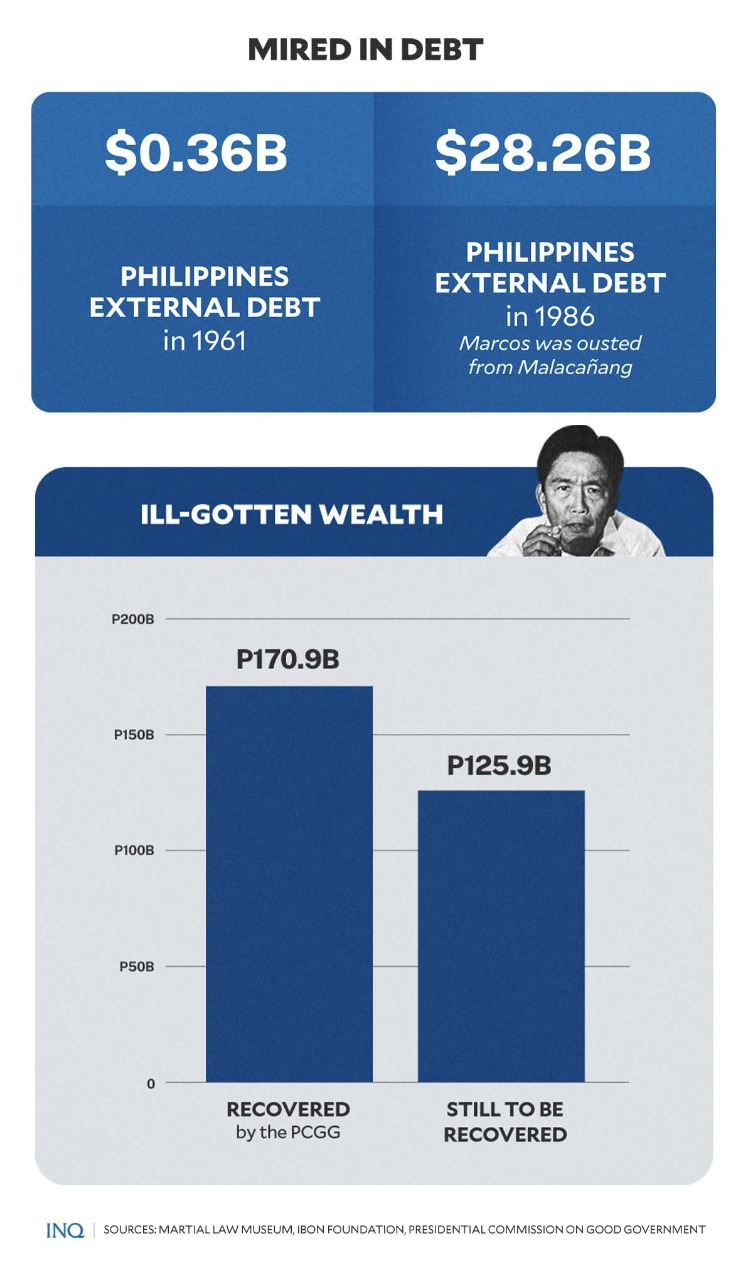

It likewise said that from $0.36 billion in 1961, the external debt of the Philippines “skyrocketed” to $28.26 billion in 1986.

READ: ‘We’ll pay Marcos debt until 2025’

Former Rep. Isagani Zarate (Bayan Muna) stressed that “we are so deep in debt that we have been paying the Marcos debt for the past 30 years since the downfall of the Marcos dictatorship.”

The think tank Ibon Foundation had said that following the loan schedule of the Philippines in 2005, “taxpayers will pay for these debts of Marcos until 2025, 39 years after he was ousted from office.”

RELATED STORY: Sereno vs Marcos revisionism: ‘Kung walang ninakaw, walang na-recover’

However, it stressed that in 2007, the Arroyo administration crowed that the era of illegitimate debt was at an end when the final installment of the loan for the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) was finally paid.

It said that the Marcos-era BNPP, which was stopped by the late President Corazon Aquino because of safety and economic concerns, continues to be the most notorious of the country’s odious debts and the Philippines’ largest foreign debt at $2.3 billion.”

This, while the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), an office created by the late former President Corazon Aquino to go after the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses and their cronies, said in 2018 that P171 billion has already been recovered.

The PCGG, which Manila Rep. Benny Abante said should already be abolished, has yet to recover P125.9 billion in ill-gotten wealth.

Abante, a Baptist pastor, said in House Bill No. 4331 filed earlier this month that the PCGG “has outlived its usefulness and has now become a big embarrassment to the government” 36 years after it was created.

‘We can’t simply forget’

Atienza stressed that the Philippines cannot move on if there is no justice and a clear acknowledgement by those complicit in inflicting martial law that severe damage had been done to society in general and human rights and the economy in particular.

“If we simply forget or we accept the lies and disinformation, the country will not learn lessons from that dark period and we will repeat the same mistakes,” she said.

She said that “the strength of a people is an acknowledgment of the past, both with the good and the bad, so that future generations will not suffer from the same mistakes.”

The Commission on Human Rights said that it honors the sacrifices of Filipinos, both prominent and unsung, and wishes to remind the people about the important roles that democracy, rule of law and human rights play in a free society and in ensuring that human dignity and rights are respected and protected.

For prisoners’ rights group Kapatid, which was first established during the dictatorship, Filipinos should resist all attempts to revise history.