Journalists are taught early on to only report the story and not become part of it to maintain the profession’s credibility and integrity. But in a system where the free press is seen as enemies, journalists find themselves making the headlines—in more ways than one.

John Reczon Calay wanted to be a teacher. He valued learning and imparting knowledge to others. But this dream soon got lost in the scheme of things when campus journalism came into his life in grade school; he fell in love with the craft since then.

The Rizal native was a wide-eyed journalism freshman at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman when Break Free, a campaign condemning the longstanding culture of impunity in the country, first took off. Organized by his first student organization, the Union of Journalists of the Philippines – UP, the annual protest commemorates the Ampatuan Massacre — regarded as the single deadliest event for journalists worldwide.

Then a first-year high school student when the massacre happened, Calay admitted he didn’t much have of an idea about it. Joining the Break Free campaign, however, helped him see the importance of knowing — and remembering.

“It was impactful to us. The victims’ relatives were right before you, revealing the culture of impunity and the number of years when justice hadn’t been served. They showed you that a brutal and greedy family can silence one of our most cherished freedoms,” he said.

Calay performs a song during the cultural night of Break Free in 2016. [Photo: Break Free/UJP-UP]

UP students stage a local protest in November 2017 to call for the end of the culture of impunity in the Philippines. [Photo: Break Free/UJP-UP]

The date Nov. 23, 2009, has since been etched in his memory, when 58 individuals, including 32 journalists, were brutally murdered after they were waylaid by the armed group led by former Datu Unsay, Maguindanao Mayor Andal Ampatuan Jr.

They were on their way to accompany the wife of then mayoral candidate Esmael “Toto” Mangudadatu in filing his certificate of candidacy in Shariff Aguak to challenge the scion of the then most powerful clan in the province — the Ampatuans.

Due to threats to his life, Mangudadatu decided to just send his pregnant wife and female relatives, thinking this would be a safer choice. As an added measure, he invited both local and national media men to cover his COC filing, but as history would show, they were not spared.

The event proved to be a tragic telltale of a flawed system. The case took more than a decade to get a verdict from the courts. The Committee to Protect Journalists, an international media watchdog, identified the Philippines as one of the worst countries for journalists in its Global Impunity Index. It has also killed aspirations; many parents discouraged their children from becoming a journalist after seeing the dangers that entailed news reporting.

Calay said the horrific event wasn’t a conversation he had at home. With the slow pace of justice, the issue soon disappeared from the media agenda. But to forget is not and should never be an option; to forgive is reserved only for the families and loved ones of those who lost their lives over a decade ago.

“We should continue to tell their stories moving forward,” said Calay. “[It’s] a way to pay tribute to our colleagues.”

Unfortunately, the Ampatuan Massacre is only one of many chapters tucked between the Philippine media’s legacy in the downfall of the dictatorship and its ongoing crusade of asserting its place in society. On paper, the press should be free. But a closer look at the fine print would show the challenges complicating this fragile freedom.

“Journalists should never be the story.”

It’s relatively simple, a tenet as old as the profession. Journalists are taught early on to simply do their job of reporting the news and distance themselves from the narrative — even in matters that directly affect them. In a traditional view, doing so maintains journalism’s credibility and integrity.

But people tend to forget that journalists, too, fall victim to a system that weaponizes disinformation and puts watchdogs in peril. The past six years bore witness to that. Not since the time of the late dictator did the Philippines have a president so blatant in his disregard for anyone who dared to hold him accountable.

In a political landscape where speaking truth to power means eating death threats for breakfast and enduring relentless persecution from the most powerful forces in the land — while still being paid less and asked to do more — journalists find themselves between covering the story and being the story. Now more than ever, it is imperative for journalists to push back and retake the narrative.

The media is in medias res.

“Is this what you want?”

A boy posed this question as a montage played of then Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte in his most vulgar — threatening to kill people, spewing curses at the Pope, giving the finger to critics. It was a political advertisement paid for by former opposition senator Antonio Trillanes—which he had admitted to bring forth the worst side of Duterte—in a bid to weaken his chances of claiming the highest position in the land. At that time, Duterte was already the leading presidential candidate in the 2016 elections.

ABS-CBN, a leading media organization in the country, ran that political ad during the final stretch of the 2016 election season; so did rival networks GMA and TV5. However, ABS-CBN was singled out over the matter, with Duterte’s running mate Alan Peter Cayetano obtaining a temporary restraining order to stop the network from airing the ad.

When Duterte ultimately captured the presidency in a landslide victory, his vendetta against ABS-CBN soon emerged. It did not sit well with the former president that the network ran Trillanes’ commercial and failed to air some of his campaign ads. Adding to his vengeful ire, Duterte accused the organization of biased reporting. He claimed that the network blocked his camp’s move to counteract Trillanes’ ad.

Since then, Duterte made it his mission to cause the media giant’s downfall. And he let it be known.

“I will see to it that you are out,” he once warned.

ABS-CBN employees light candles in solidarity as the network’s darkest hour came in May 2020. [Photo: Edwin Bacasmas]

Mark Escarlote remembered it all too well. A distinguished veteran in sports journalism, Escarlote was one of the pillars of ABS-CBN Sports, regarded by many in the industry as a standard for sports coverage. Name a sports event of paramount importance and their team would be there, providing the readers with stories from within and beyond the dugout.

Even from his first day with the organization, Escarlote could already see himself retiring as a Kapamilya. In 2014, he and four other colleagues built the network’s digital sports department from scratch; at its peak, ABS-CBN’s integrated sports department had already become an undeniable tour de force. Apart from the work environment and the compensation, this legacy was the reason he felt so connected with the network.

“You can really see your growth, and they will make you feel how important you are,” he said. “That’s why it was hard for me when we lost the franchise.”

Escarlote (second from right) and the four other pillars of ABS-CBN’s digital sports section pose for a photo in August 2020, three months after ABS-CBN lost its franchise. [Photo: Santino Honasan]

In February 2020, then Solicitor General Jose Calida filed a quo warranto petition before the Supreme Court to stop the operations of ABS-CBN due to supposed violations of its franchise. Calida claimed the network allowed foreigners to own Philippine mass media — a violation of Article XVI, Section 11 of the 1987 Constitution. He also alleged that KBO, one of ABS-CBN’s pay-per-view channels, ran outside the network’s franchise provisions.

The network maintained it did nothing wrong. Calida’s petition, however, served as a catalyst for closer scrutiny of the network’s efforts to have its franchise renewed. The attacks were relentless, and Malacañang executives and administration allies took turns in getting their kicks.

READ: ABS-CBN has no tax delinquency; ‘regularly’ paying taxes – BIR exec

In the Philippines, a media network must obtain a 25-year congressional franchise to broadcast over television and radio. ABS-CBN’s franchise, granted upon the passage of Republic Act No. 7966 in 1995, ran until May 4, 2020. But the network’s first attempt to renew its franchise in September 2014 lapsed at the committee level, so it only meant one thing: ABS-CBN had no choice but to do it in Duterte’s time.

The former president’s strife with the media giant is anything but a secret. Referencing the election advertisement issues from 2016 and an alleged slanted coverage against his administration, Duterte repeatedly said he would do everything in his power to prevent ABS-CBN’s franchise renewal. These renewed attacks pushed bills seeking to extend the embattled network’s franchise to the sidelines.

Malacañang insists that the decision to deny ABS-CBN’s franchise did not come from the executive department as it claims that press freedom in the country is not under attack.

Here are some of President Duterte’s previous pronouncements against the embattled media giant. pic.twitter.com/Vp7UggSqbn— Inquirer (@inquirerdotnet) October 11, 2021

More than ever, ABS-CBN found itself fighting for its existence, with its franchise sitting cold in the arms of Duterte’s supermajority in Congress. To test his citizenship and allegiance, ABS-CBN chairman emeritus Gabby Lopez was asked to recite the first lines of the Panatang Makabayan by Rep. Rodante Marcoleta during a House hearing. ABS-CBN president and CEO Carlo Katigbak also apologized to Duterte over the controversial ad the network aired in 2016 during a Senate hearing.

“It was hard watching those hearings. It felt like mental torture,” Escarlote said. Seeing how lawmakers treated his bosses, he knew it was game over.

On May 5, 2020, just two days after World Press Freedom Day, franchise-less ABS-CBN was ordered by the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) to stop its broadcast operations. After the airing of its primetime newscast TV Patrol, the network officially signed off at 7:52 p.m.

For the second time in its history–the first during martial law–ABS-CBN has gone off-air.

Anxiety was high inside the organization. Everyone feared getting that one phone call saying they had to be laid off; Escarlote, for his part, still hoped that the digital sports section would remain. But the absence of sports events during the pandemic meant less content, and less content meant lower revenues from the department. From an executive standpoint, Escarlote knew his team was standing on thin ice.

On July 10, 2020, the House of Representatives sealed ABS-CBN’s fate when it voted 70-11 to deny the media giant a brand new franchise. That same day, Escarlote and the rest of ABS-CBN’s integrated sports department were notified of their retrenchment.

Escarlote is part of the first wave of layoffs in August 2020, followed by another in October. At least 4,000 employees of the network were suddenly left jobless amid an economic recession and a worsening health crisis.

Supporters and employees of ABS-CBN, the country’s largest broadcast network, hold placards as they join a protest in front of the ABS-CBN building in Manila on Feb. 21, 2020. [Photo: Basilio Sepe/AFP]

ABS-CBN’s shutdown and franchise denial met widespread condemnation from various groups and critics, likening Duterte to the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. who was the first president to order the network’s closure in 1972. If anything, the issue exposed a fatal flaw in press freedom in the country — that broadcast media organizations sit at the mercy of politicians. No one ever imagined that an esteemed institution like ABS-CBN would face such a consequence.

What happened is not lost on Escarlote: For him, it sent a grim message to the rest of the industry.

“You see that giant network? We brought that down. The same can happen to you.”

–

In his second State of the Nation Address in 2017, Duterte launched a scorching offensive against media organizations that had been critical of his rule. One of the targets was Rappler, whose hard-hitting coverage of the Duterte administration and its deadly drug war earned the ire of the former president.

“You are supposed to be 100 percent Filipino. And yet when you try to pierce their identity, it is fully owned by Americans,” he claimed.

Rappler had repeatedly debunked this accusation, maintaining that while it has foreign investors, the organization remains fully Filipino-owned. In a razor-sharp statement a month after Duterte’s address, Rappler expressed dismay: “We don’t mind being criticized; we just ask that it be honest and factual.”

But their call fell on deaf ears.

[Photo: Ted Aljibe/AFP]

On Jan. 11, 2018, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) revoked Rappler’s operating license for allegedly violating the Constitution. Their basis? That Rappler violated constitutional provisions on mass media ownership and control.

It primarily put into question the investment of Omidyar Network, a self-styled “philanthropic investment firm” created by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, through Philippine depositary receipts (PDRs). But PDRs don’t grant ownership and control to the holder, and they aren’t rare — even other mass media outlets in the country have issued such instruments to foreign investors.

Lian Nami Buan held vivid memories of four years past. A justice beat reporter, she is no stranger to online vitriol. Her stories were more often than not at the receiving end of unfavorable reactions; a quick social media search of her name would show questionable accounts maligning her work and character.

The night before the SEC order, Buan said they were told to be in the office no matter what. When the decision was brought down the next day, they were all in a general assembly led by Rappler CEO and Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa.

“It was very reassuring,” Buan said. “She told us not to worry about it, that our jobs were secured, and that we were all prepared for this. Maria had her game face on, and so did the other editors.” At the time, she even felt like those who cared about Rappler were “more stressed than [they] were.”

Maria Ressa speaks during a press conference at their office in Manila on Jan. 15, 2018, while acting managing editor Chay Hofilena listens. [Photo: Ted Aljibe/AFP]

But the trials kept coming for the organization. A week after the revocation, the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) subpoenaed Ressa and former Rappler reporter Reynaldo Santos Jr. over a cyber libel complaint by businessman Wilfredo Keng. The case stemmed from a Rappler report claiming that Keng lent his sports utility vehicle to the late Chief Justice Renato Corona.

The story in question was published on May 29, 2012. The cybercrime law, on the other hand, was enacted in September 2012. Essentially, there should have been no case since penal laws cannot be applied retroactively.

However, Rappler corrected a typographical error in the article on Feb. 19, 2014. The Department of Justice used this to say that the cybercrime law now applies to the story because it was “republished.”

In what was seen as a politically motivated move, NBI officers arrested Ressa in February 2019, with the journalist having to spend a night in jail before being able to post bail. In June 2020, Ressa and Santos were convicted of cyber libel by a Manila regional trial court; various critics and media advocates strongly condemned the decision and considered it a blow to press freedom.

In the midst of it all, Rappler firmly stood their ground, come revocation or criminal charge. “In our culture, the more that you harass us, the more that we feel empowered,” Buan said. “Not to say we are masochists. Of course, nobody wants that; we all want it to stop. But that’s really the effect on us.”

Their resilience, however, continues to be tested. In June 2022, the SEC upheld its earlier ruling to revoke Rappler’s license, which Ressa said the organization would be appealing. The following month, the court stood by its conviction of Ressa and Santos.

–

The media was right to take Duterte’s words with a grain of salt when he said at the start of his presidency: “Do not hesitate to attack me, criticize me, if I do wrong in my job.” After all, this was the same Duterte who said that a journalist is “not exempted from assassination if (you) are a son of a bitch.”

Press freedom has immensely suffered for the past six years under Duterte, whose administration was defined by its relentless assault on its critics, particularly in the media. Reporters Without Borders, a Paris-based media watchdog, included the country’s previous chief executive in its 2021 “press freedom predators” list, underscoring the leader’s “total war against independent media.”

In response, Malacañang dismissed the report, saying that press freedom “is alive and well in the Philippines.”

READ: SWS: 45% of Filipinos think it’s dangerous to print or air anything critical of the administration

One of the Duterte administration’s most infamous attacks against the press was the release of the so-called “Oust Duterte matrix” in April 2019. First published by the Manila Times, it contained personalities and groups—primarily journalists and media organizations critical of the former president—involved in an alleged plot to overthrow Duterte.

LOOK: The “Oust-Duterte Plot” matrix released by Malacañang. | @NCorralesINQ

READ: https://t.co/9bA7TbtlzC pic.twitter.com/1xhnaIcEBt

— Inquirer (@inquirerdotnet) April 22, 2019

Ellen Tordesillas, one of the tagged individuals in the matrix, couldn’t help but laugh at the memory. A veteran journalist since the Marcos dictatorship, Tordesillas is the president of the independent news organization Vera Files, known in the online frontier for its fact-checking initiatives and in-depth stories on underreported issues.

“I didn’t take it seriously because it’s so preposterous,” Tordesillas said.

Instead, she was worried about the others accused by the government who weren’t used to this kind of harassment, like Hidilyn Diaz, the country’s first Olympic gold medalist. She also expressed concern about the frequency of unreliable reports reaching Duterte — a recurring theme in his presidency.

“It could have been funny,” Tordesillas said, “if only it didn’t involve lies.” And lies, especially during the Duterte administration, serve as a precedent for far greater dangers.

For instance, red-tagging — labeling groups and individuals considered critical of the government as “communists” or “terrorists” — has intensified and become deadlier since Duterte came into power. These allegations have been handed all around, journalists included.

Len Olea, the managing editor of alternative media outfit Bulatlat, is all too familiar with this reality. Her organization has been constantly vilified by state forces as communist fronts; they have also suffered cyberattacks in the form of distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks—which a Swedish digital forensic group traced to the Philippine Army.

Recently, the NTC, acting on mere request of then National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon, ordered to block several websites, including Bulatlat’s, which it said are “affiliated to and are supporting terrorist and terrorist organizations.”

READ: NTC orders websites ‘affiliated with, supporting terrorist organizations’ blocked

These attacks on the press, Olea said, clearly show that those in power only wanted the public to “believe in their own version of the narrative” because they are afraid of the truth.

“We [journalists] don’t want to be the story, to be honest,” Olea said. “But because we are under attack, we have no choice but to confront this.”

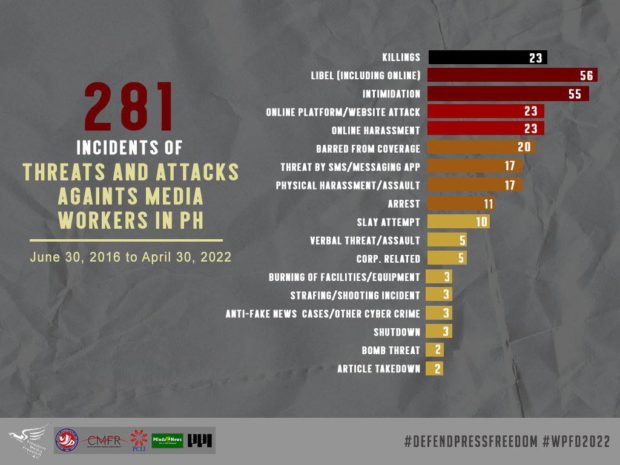

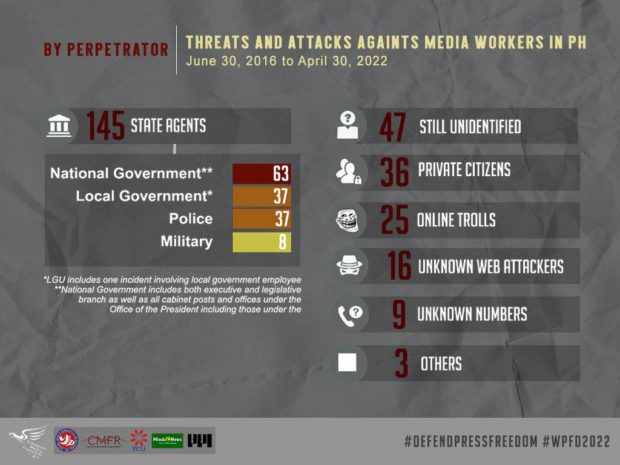

The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) identified 281 incidents of threats and attacks against media workers, including 23 recorded killings, during the Duterte administration. Out of the total number, 145 were perpetrated by state agents.

No wonder the Philippines’ ranking dropped in the latest World Press Freedom Index to 147th place among 180 countries.

[Photos: NUJP]

Given his legacy as the media’s main tormentor in the past six years, it might seem ironic that Duterte declared Aug. 30 of every year as National Press Freedom Day in honor of Filipino writer Marcelo H. Del Pilar.

Today, the country marks its first—and no less under President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the son and namesake of the late dictator.

Journalists and media groups have expressed their wariness of the new administration early on. Marcos Jr.—whose absence in debates and reluctance to entertain ambush interviews tainted the entirety of his campaign—once said he would face the media, quipping a president should be “capable of explaining anything.”

NUJP chairperson Jonathan De Santos, who noted the Marcos campaign’s seeming disdain of the press, stressed how the previous administration created a template for dealing with journalists and media organizations.

“It also gave a lot of people the signal that the press is a legitimate target,” De Santos said. “No matter who wins the presidency, the tools and the precedent will be there for them to use.”

Three months in, journalists have already seen some challenges. Access to the president has become a sore point. Olea said they received reports of media questions being screened before Marcos would even answer. Buan, who covered his campaign, observed how the current rule is “slowly chipping away at the importance of the legacy media.”

“Sometimes, it doesn’t feel like a threat, but it’s lulling you into complacency,” Buan said. “And if they succeed at that and if we let it, we won’t know years from now that the free press would have changed drastically, and we didn’t even know that it happened.”

One of the biggest dangers currently faced by the media is the endless wave of lies being weaponized in a country regarded as “patient zero” in the global disinformation epidemic. In 2018, Rappler reported that it found millions of bogus social media accounts spreading fake news connected to the Duterte campaign. Social media platform TikTok, which has been remolded into a political battleground, saw Marcos-related content amassing billions of views—far ahead of his rivals.

READ: Fake news persists in ‘patient zero’ PH: Lies live in too many ways

In a landscape where disinformation is deeply entrenched in the public sphere to the point that journalists are demonized and discredited for amplifying the truth, the industry faces the urgent challenge of regaining the people’s confidence. The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that only 37 percent of the public believes the news.

To restore this trust, Buan said journalists should take a more proactive role in helping the audience get the correct information. “Because purveyors of lies are incentivized to spread even more lies, our job as guardians of the truth has evolved into a role where we need to help people understand and identify the lies from the truth,” she said.

Meanwhile, Tordesillas called on fellow journalists to rise to the challenge of helping the people understand the media’s role in a functioning democracy “in terms that they would understand.” She stressed that while it might be tempting to fight fire with fire, journalists should hold on to their most potent weapon: the truth.

“If you don’t adhere to what is truthful, what is the alternative?”

“What is journalism for?”

In their book The Elements of Journalism, Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel came up with a definition that has remained true over the years: journalism’s primary purpose is to provide citizens with the information they need to be free and self-governing. In a system riddled with political dynasties and economic inequality, the fourth estate serves as a watchdog, paves the way for crucial conversations, and provides a platform for the forgotten.

De Santos, who has been in the industry for 14 years, would like to think he’d be doing this for a long time. But for him, it’s also a constant negotiation of whether it’s worth it to stay, given the poor economic conditions of media workers further exacerbated by the current national crisis.

Facing what is now an existential battle, journalists simply cannot run on passion alone.

“I wish the industry took better care of its workers. Let’s not treat media workers as just another part of an assembly line,” he said.

Still, he is looking forward to better times. Press freedom, as much as it is a pillar of democracy, is also a struggle that needs constant tending. De Santos admitted that the media “could have done better” to defend its ranks for the past six years, but there are only lessons to be learned.

“We need to look out for each other and work together. Reach out to a colleague. Support each other’s work. Fighting for press freedom does not need to always be a big statement,” he said.

Administrations might come and go, but the press will always be there to keep holding power to account. And to ensure that the flames of a hard-fought democracy will continue burning, a lesson from history should always be remembered: that the truth should always be free.

The media is in the midst of things.