Stagflation: What is it and why is it a cause for concern?

MANILA, Philippines—The World Bank, when it announced the global growth forecast for 2022 earlier this month, warned of the risk of “stagflation” amid the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

On June 7, the World Bank slashed its global growth forecast by 1.2 percentage points to 2.9 percent for 2022.

It added that the outlook could still grow worse as the war in Ukraine further highlights the slowdown in the global economy, which was already entering what could become “a protracted period of feeble growth and elevated inflation.”

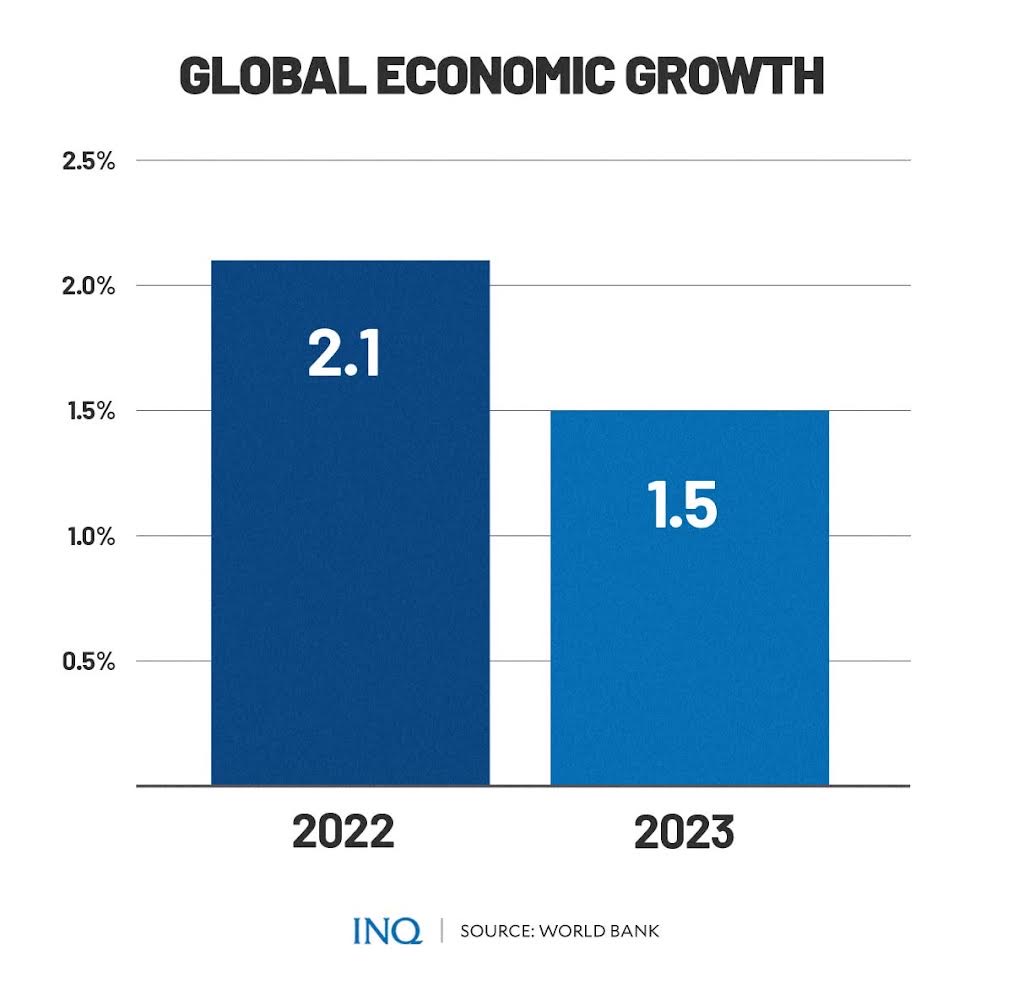

World Bank president David Malpass said at a news conference that global growth could fall to 2.1 percent in 2022 and 1.5 percent in 2023, driving per capita growth close to zero, if downside risks materialized.

Malpass added that the global growth was being hammered by several factors, raising the risk of stagflation—a situation the world has not seen since the 1970s.

“The danger of stagflation is considerable today,” Malpass wrote in the Global Economic Prospects report.

“Subdued growth will likely persist throughout the decade because of weak investment in most of the world. With inflation now running at multi-decade highs in many countries and supply expected to grow slowly, there is a risk that inflation will remain higher for longer.”

READ: World Bank slashes global growth forecast to 2.9%, warns of ‘stagflation’ risk

With the World Bank’s warning, questions have been raised about stagflation, including what it really means, why experts are concerned about it, why it matters, and whether it will heavily impact the Philippines.

What is stagflation?

Stagflation is a term that combines the words stagnation and inflation.

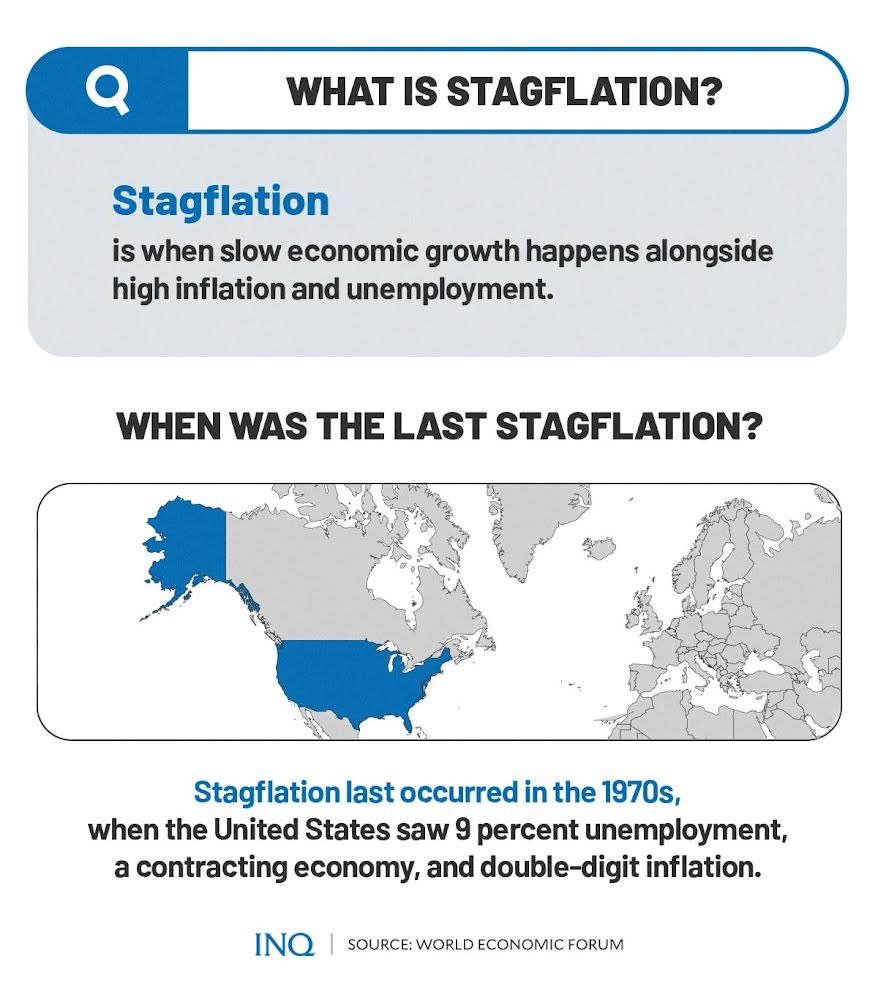

According to the World Economic Forum, stagflation is a period that occurs when slow economic growth coincides with persisting high inflation and high unemployment or joblessness.

Low unemployment, under good economic conditions, usually pushes employers to raise wages to keep or attract workers—which, in turn, raises consumer demand and drives price increases.

Meanwhile, in a slow economy, wages usually become stagnant, demands are reduced, and prices are slashed—the latter helps ease financial strain for those who have lost their jobs or experienced pay cuts.

However, as explained by Veronika Dolar— professor of economics at Long Island-based State University of New York Old Westbury—in an article by ABC News, “on rare occasions…high inflation persists even as the economy slows and unemployment rises.”

This, according to Dolar, results in stagflation.

Stagnation describes a malfunctioning economy, in which prices of commodities continue to rise while economic growth—the increase in the amount of output of goods and services—plummets.

Slow economic growth can further lead to a higher rate of joblessness over time.

Why does it matter?

Stagflation affects or hurts people in different ways.

In times of stagflation, there is heightened financial risk wherein commodity items—such as oil, wheat, steel and other goods—become more expensive while consumers receive less income.

Even for households that have managed to keep their jobs, stagflation remains a huge problem as their purchasing power becomes eroded by sudden price hikes for everyday commodities.

While consumers pay for higher prices of goods and services—and not being able to consume more—they also have to face the risks of losing their jobs.

Overall, stagflation is a really concerning situation because it is the opposite of what the public wants and needs: a booming economy with low prices of commodities.

Experts have also noted that stagflation is hard to fix.

Then vs now: Factors causing stagflation

In the 1970s, one of the biggest factors that contributed to stagflation—according to studies—was the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), a group of oil-producing nations.

According to economist Dr. Sarah Hunter, the Opec group restricted the supply of oil to the global market in the 1970s, causing an oil price shock. Oil price, as a result, rose rapidly during the said period—and later on, led to inflation.

During the same period, the US saw a 9 percent unemployment rate, a contracting economy, and double-digit inflation.

“Stagflation is as an old ghost rising from the past, born out of the fears of an older generation and the interest of a new one that has adopted crypto currencies for a fair lady,” said Sebastien Galy, senior macro strategist at Nordea Asset Management.

This time, the World Bank said global inflation—at “multi-year highs”—and the slowing economic growth due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have raised the risk of stagflation.

“Global inflation has risen sharply from its lows in mid-2020, on rebounding global demand, supply bottlenecks, and soaring food and energy prices. Markets expect inflation to peak in mid-2022 and then decline, but to remain elevated,” said the World Bank.

“Global growth has declined sharply since the beginning of the year and, for the remainder of this decade, is expected to remain below the average of the 2010s,” it added.

“This has raised the risk of stagflation: a combination of high inflation and sluggish growth.”

In a statement released last June 7, the World Bank said the current global economic situation resembles the 1970s stagflation in three aspects.

These include the “persistent supply-side disturbances fueling inflation, preceded by a protracted period of highly accommodative monetary policy in major advanced economies, prospects for weakening growth, and vulnerabilities that emerging markets and developing economies face with respect to the monetary policy tightening that will be needed to rein in inflation.”

However, the World Bank has also weighed in on the differences between the current juncture and stagflation in the 1970s, explaining that:

- the dollar now is strong compared to its severe weakness in the 1970s

- the percentage increases in price of commodities are smaller now compared back then

- major financial institutions’ balance sheets are generally strong.

“More importantly, unlike the 1970s, central banks in advanced economies and many developing economies now have clear mandates for price stability, and, over the past three decades, they have established a credible track record of achieving their inflation targets,” said the World Bank.

“The experience of the 1970s is a reminder that there is a considerable risk that inflation remains high or continues to rise if supply shocks persist, inflation expectations become unanchored, or long-term disinflationary forces fade,” it added.

PH nowhere near stagflation, for now

Amid the World Bank’s warning, however, think tank Oxford Economics noted that the Philippines is among the emerging markets (EMs) least vulnerable to stagflation.

Based on Oxford Economics’ latest stagflation risk scorecard, the country ranked second to the last out of 18 EMs in terms of vulnerability to stagnation, with a score of 4.5 out of nine despite global tensions.

According to Lucila Bonilla—Oxford EM economist—and Gabriel Sterne—Global Strategy Services and EM Macro Research head—the Philippines, along with the Czech Republic, Indonesia, Poland, and Peru are the “best performers” amid the rising risk of stagflation and the elevated global prices of commodities.

Among the Philippines’ strengths, the economists said, are “muted impulse and amplification factors.”

Oxford Economics’ stagflation scorecard measures 12 vulnerability metrics under four risk categories. These categories include impulse and amplification, policy responses, policy credibility, and structural change.

Last February, Moody’s Analytics’ chief Asia-Pacific economist Steven Cochrane said in a report that the Philippines was nowhere near dreaded stagflation.

“There is no reason to worry about stagflation. At least not yet,” said Cochrane.

“Stagflation is a persistent period of high inflation, with slow economic growth and high unemployment. The Philippines’ economy right now is quite dynamic and does not fit these criteria,” Cochrane added.

READ: Economists: No stagflation yet, but higher prices of goods to linger

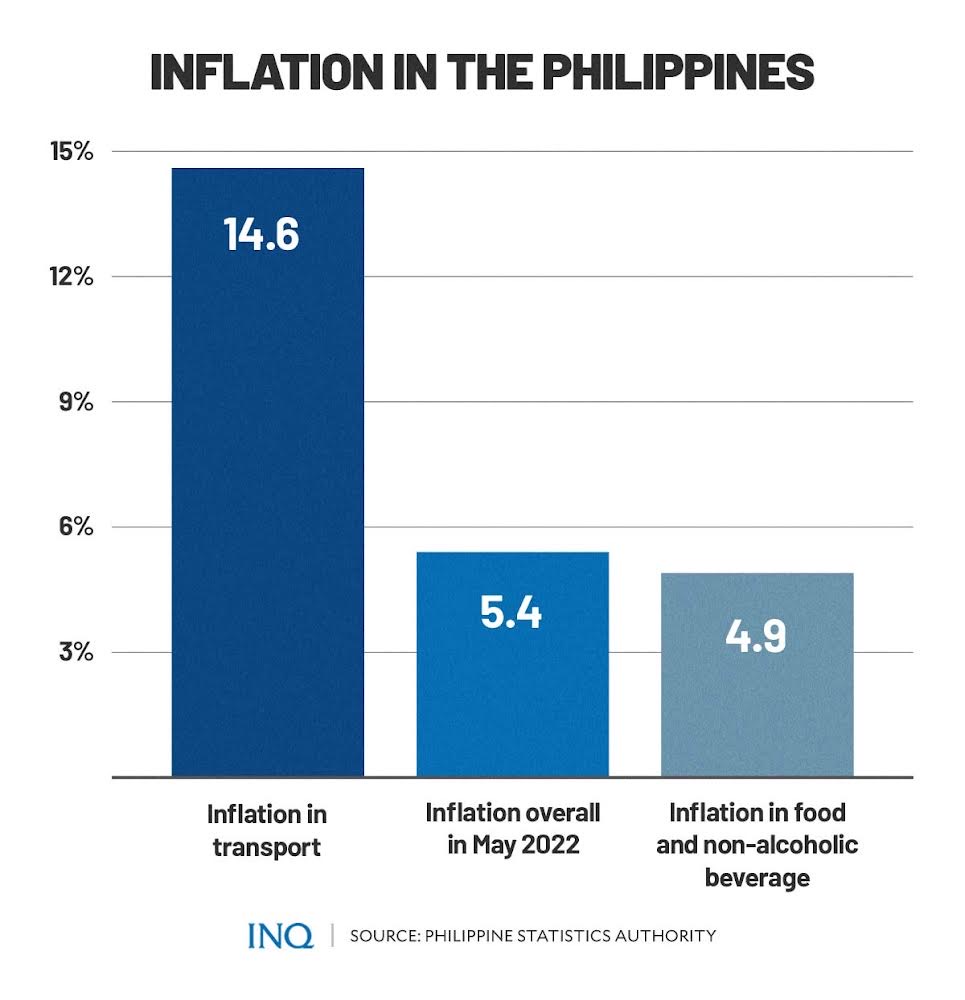

Based on data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the country’s year-on-year inflation rate in May accelerated to a 42-month-high of 5.4 percent from 4.9 percent in April.

READ: May inflation rate heats up to 42-month high of 5.4%

The acceleration in the country’s inflation rate for the month of May, according to PSA, was due to higher annual growths in the food and non-alcoholic beverages index (4.9 percent) and transport index (14.6 percent).

The following commodity groups likewise contributed to the upward trend of headline inflation during that same month:

- Alcoholic beverages and tobacco, 6.8 percent;

- Clothing and footwear, 2.1 percent;

- Recreation, sport and culture, 1.7 percent; and

- Personal care, and miscellaneous goods and services, 2.5 percent.

Meanwhile, the PSA reported that growth in the country’s gross domestic product for the first quarter of 2022 was 8.3 percent—higher than the median analyst forecast of 6.7 percent. The economy grew by 1.9 percent compared to the fourth quarter of 2021.

READ: PH GDP grows 8.3% in Q1 2022, says economic managers

“We have restored many jobs and livelihood by shifting to a more endemic mindset, accelerating vaccination, and implementing granular lockdowns that only targeted the areas of highest risk while allowing the majority of our people to work and earn a living,” the country’s economic managers said.

“Growth in the first quarter of 2022 was broad-based as most sectors rebounded from their contractions in the same period last year,” they added.

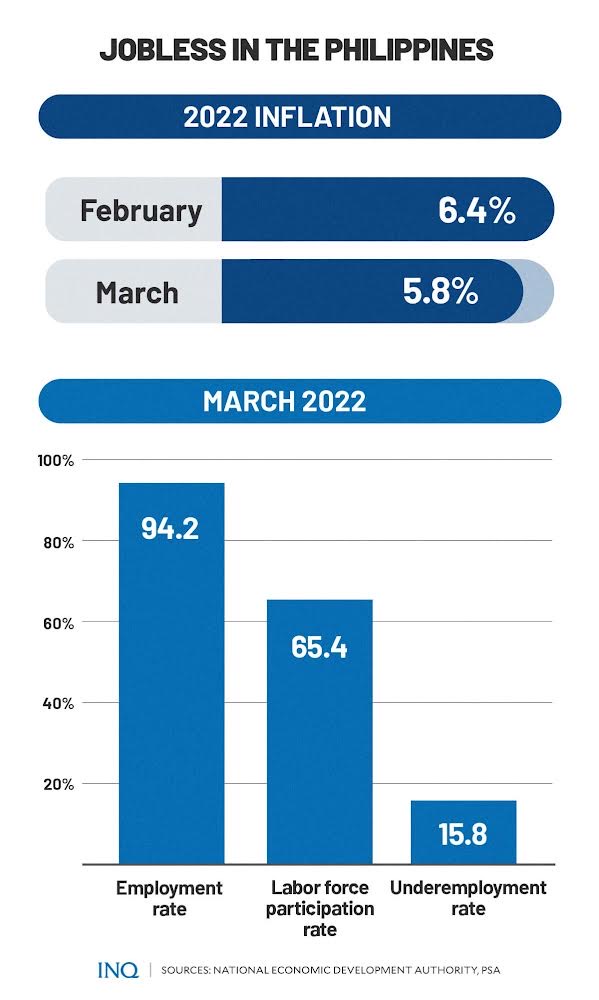

As of March 2022, the unemployment rate in the Philippines stood at 5.8 percent—a record-low since the start of the pandemic. The figures also decreased compared to 6.4 percent recorded in February.

Data from the National Economic Development Authority (Neda) and PSA showed that the country’s labor force participation rate during that same month was 65.4 percent.

The employment rate reached 94.2 percent, while the underemployment rate—the percentage of employed persons expressing the desire to have additional work hours or a new job with longer working hours—was 15.8 percent.

The PSA’s latest preliminary 2021 annual labor market statistics showed that there were 3.73 million Filipinos with no jobs in May.

Meanwhile, the employment rate stood at 92.3 percent, which translates to 44.72 million Filipinos with jobs during the same month. The labor force participation rate was at 64.6 percent.