Speaking to those who can’t hear: Why sign language matters in campaigns

MANILA, Philippines—It was already six years since Chona Calnison, 41, ended her 15-year career as a teacher for the deaf, but at the March 17 #LayagLeniKiko People’s Rally, she decided to “interpret” again.

She told INQUIRER.net that as she saw Vice President Leni Robredo’s campaign unfold in Quezon City, Cebu and Iloilo, she was elated when told that one will be held in Zamboanga City, where she is staying.

READ: ‘An inspiration’: Zamboanga City mayor roots for Robredo in presidential race

Calnison, who is a psychotherapist now, worked for only half day on March 17 as she wanted to take part in Robredo and Sen. Kiko Pangilinan’s #LayagLeniKiko People’s Rally which had an estimated crowd of 35,000 people.

READ: ‘Pink’ crowd defy rain for Robredo grand rally in Zamboanga City

She said she only saw herself as one of the thousands of individuals there, but since there was a need to interpret for the deaf, who were in Zamboanga City’s Cesar F. Climaco Freedom Park, she decided to help.

“That day, I received a call saying they needed a sign language interpreter since no one was available because most are public school teachers and they did not want to risk their employment,” Calnison said.

The Civil Service Commission and the Commission on Elections (Comelec) bars civil servants from engaging in electioneering or partisan political campaigns to make certain that they are “focused on public service”.

Since she was already a private worker, Calnison said she decided to extend help, saying it was her way of sharing “radical love”—the reason that while she was asked about her rate, she interpreted for the deaf without pay.

She said people with hearing problems, who were present at the March 17 rally, came all the way from Zamboanga Sibugay and Zamboanga City to listen to what Robredo, who is seeking the presidency, had to say.

RELATED STORY: Leni Robredo tells Zamboanga: Our boat can still hold more ‘kakampinks’

‘It’s what they deserve’

For Calnison, the presence of interpreters is significant, especially this election, saying that it highlights the needs of persons with disabilities (PWDs) and even reflects the kind of government that the candidate is trying to present.

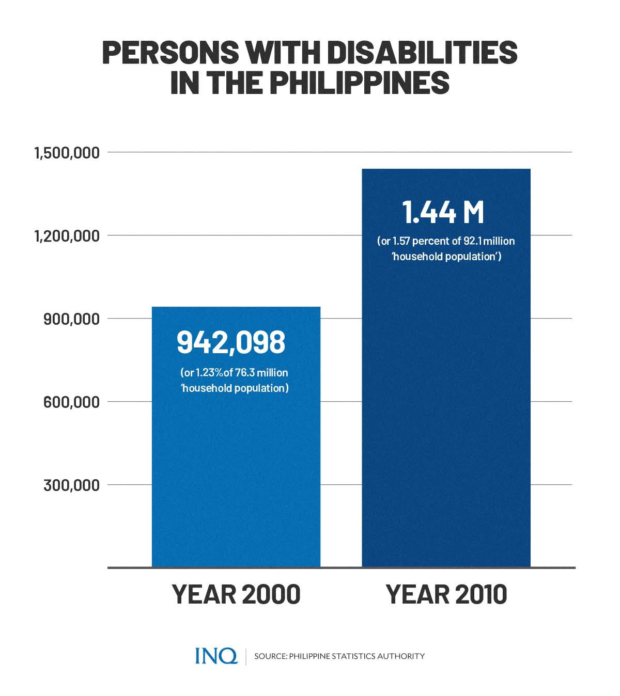

The Philippine Statistics Authority’s (PSA) Census of Population and Housing revealed that in 2010, there were 1.44 million PWDs—497,902 more than 942,098 PWDs in 2000.

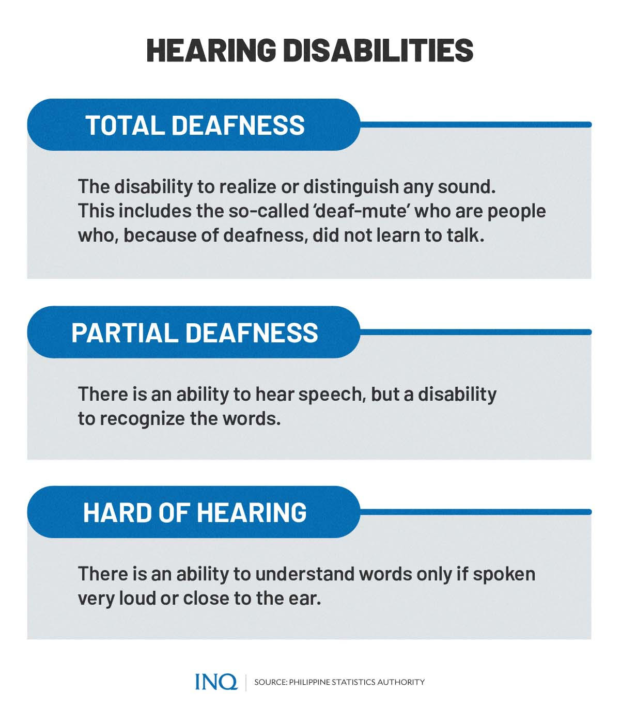

In 2000, about 3.81 percent of PWDs, or 35,890 individuals, had total deafness, which is the disability to realize any sound, like the so-called “deaf-mute” or people who, because of deafness, did not learn to talk:

- Below 1 year old: 260

- 1-4 years old: 1,526

- 5-9 years old: 3,683

- 10-14 years old: 4,387

- 15-19 years old: 3,589

- 20-24 years old: 2,767

- 25-29 years old: 2,311

- 30-34 years old: 2,161

There were 40,983 individuals—4.35 percent of the 942,098 PWDs in 2000—with partial deafness, which is the disability to discriminate words even if there is an ability to hear:

- Below 1 year old: 193

- 1-4 years old: 1,079

- 5-9 years old: 2,322

- 10-14 years old: 2,707

- 15-19 years old: 2,230

- 20-24 years old: 1,658

- 25-29 years old: 1,438

- 30-34 years old: 1,402

In 2000, there was 4.75 percent, or 44,725 individuals, with hard of hearing condition, or people who can only hear and discern words only if spoken “very loud or close to the ear”:

- Below 1 year old: 46

- 1-4 years old: 331

- 5-9 years old: 992

- 10-14 years old: 1,312

- 15-19 years old: 1,001

- 20-24 years old: 810

- 25-29 years old: 802

- 30-34 years old: 837

Calnison said when she learned that the deaf were there in the rally with them, she was certain that “it was their way of telling the world that they also need to take part, to exercise their right, and to receive access to information.”

“Without sign language interpreters, I think they will be deprived of what they need to understand the things that are happening […] It’s what they really deserve,” she said.

She said the presence of people with hearing problems indicates that people come not because of the “concerts,” stressing that when individuals seeking elective offices started to talk, they gave their “complete attention”.

Calnison said the deaf listened to the messages through her interpretation and this helped them make decisions, especially on who to vote for by giving them the chance to understand who should be elected to the presidency.

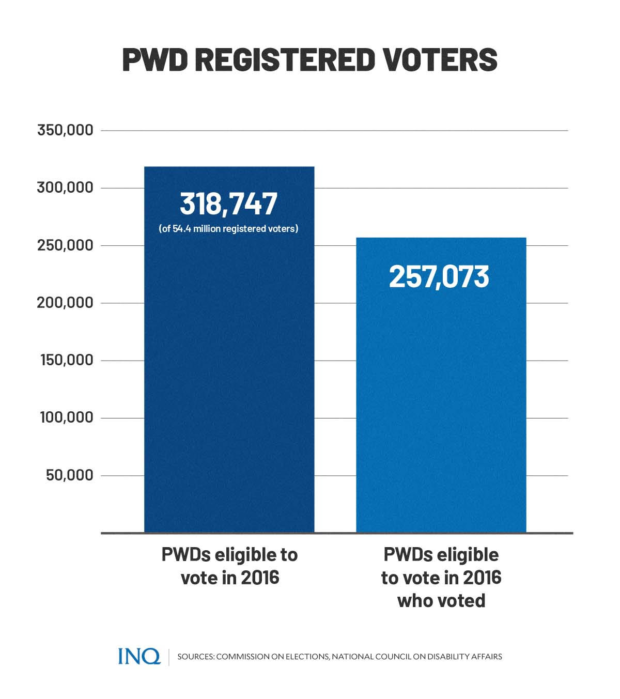

In the 2016 elections, there were 318,747 PWDs who were eligible to vote—0.59 percent of 54.4 million registered voters. The Comelec and the National Council on Disability Affairs said there were 257,073 who voted on Election Day.

‘Sign of love’

Last March, a Facebook page shared a photo of Robredo and Pangilinan, falsely saying that they made the “devil’s sign” at the Paglaum People’s Rally held in Bacolod City, Negros Occidental.

However, what the two really did was gesture the sign for “I love you” since the event, which had a crowd of 70,000 people, likewise had PWDs who even helped in keeping the Paglaum Sports Complex clean.

For Calnison, the post, which likened the “I love you” sign to the one that could explain one’s links with an international criminal gang, was an “insult” to people who have hearing problems.

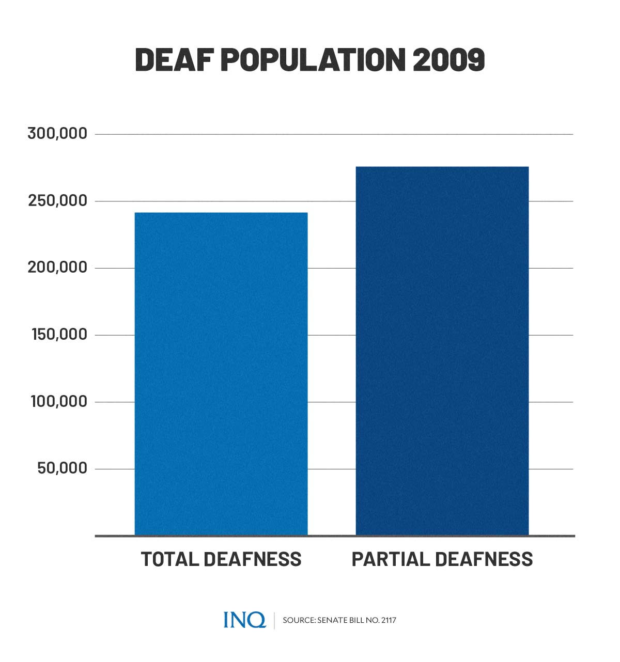

In 2014, then Sen. Bam Aquino said in Senate Bill (SB) No. 2117 that the “deaf population” in 2009 was already 517,536—241,624 people with total deafness and 275,912 people with partial deafness.

Calnison said Robredo’s “I love you” sign was loved by the people, especially by PWDs because they sensed that she was giving them what they deserve–that they will likewise benefit in Robredo’s “Angat Buhay Para sa Lahat”.

She said that Robredo’s leadership, “as early as now,” is embracing everyone. “If she wins, I think PWDs, especially the deaf, will be given what they need, they will be given what they deserve,” she said.

The National Survey of Hearing Loss in the Philippines said 15 percent of Filipinos have moderate or serious hearing loss and that the prevalence of this is high in the Philippines.

The findings, which were outlined by Hear It on its website last year, revealed that the prevalence was 7.5 percent in children, 14.7 percent in people who are 18 to 65 years old, and 49.1 percent in people who are 65 years and older.

PH law

It was in 1992 when Republic Act (RA) No. 7277, or the Magna Carta for Persons with Disabilities, was signed to protect the welfare of PWDs.

Section 22 of the law said that television stations are “encouraged” to provide sign language “inset or subtitles” in one news program a day and special programs which cover events of national significance.

With SB No. 2117 requiring sign language insets in news programs, Aquino said it values transparency and news should be made accessible, especially to PWDs and those with hearing problems.

He said, quoting the late President Ramon Magsaysay, “those who have less in life should have more in law” which meant Filipinos who have hearing problems should be provided with the learning “which many of us take for granted”.

On Oct. 30, 2018, President Rodrigo Duterte signed RA No. 11106 which declared the Filipino Sign Language (FSL) as the “national sign language” of the Filipino deaf and of the government.

READ: Duterte signs Filipino Sign Language Act

This was in compliance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which is intended to protect the rights and dignity of PWDs.

RELATED STORY: Basic phrases to get started on learning Filipino Sign Language

The law finally provided that the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas should require insets of FSL interpreters in news programs within one year from the effective date of the law.

‘Far from over’

Calnison said that while the FSL law was considered as a “milestone,” especially now that FSL insets are becoming more visible, the fight for the rights of PWDs, especially the deaf, is still far from over.

She said that since her employment as a teacher for special education (SPED) in 2003, classrooms for students with special needs were not given enough attention.

“One classroom was divided into three or four, there were problems with the roofing, wirings, and even ventilation. When I was already retiring, classrooms were still the same,” she said.

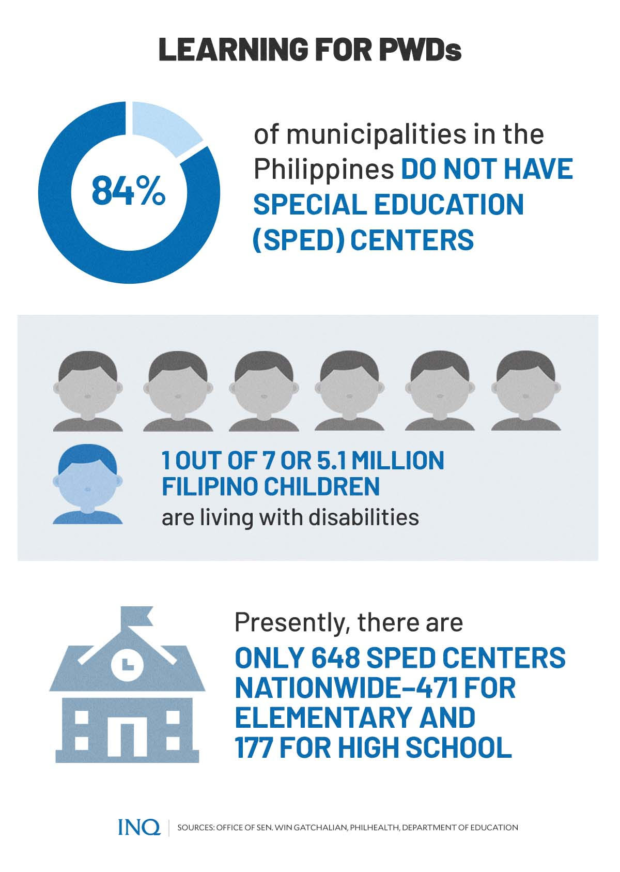

One out of seven—or 5.1 million Filipino children—are living with disabilities, Sen. Win Gatchalian said in 2020, but 84 percent of municipalities in the Philippines does not have SPED centers.

Presently, there are only 648 SPED centers in the Philippines—471 in elementary schools and 177 in high schools. This was the reason that he proposed the establishment of SPED centers through SB No. 171.

RELATED STORY: Teachers, parents share burden of educating special needs students

He said the existence of SPED centers or Inclusive Education Learning Resource Centers will make “quality education” accessible to children and youth with disabilities or special needs.

The Department of Education said the “ideal pupil/student—teacher ratio” for SPED is 15:1. There are only 2,601 SPED teachers in elementary schools and 284 in high schools in 2018.

According to the PSA’s 2016 National Disability Prevalence Survey, three out of five respondents are working, mostly in private establishments, while some are self-employed without any employee.

Robredo, last Feb. 18, signed a covenant with PWDs, saying that should she win the presidency on May 9, she will implement the accessibility law and will give greater health care for PWDs.

Former Sen. Ferdinand Marcos Jr. promised that he will provide PWDs with equal access to opportunities, stressing that they are an “important partner in nation-building.”

Sen. Panfilo Lacson and vice presidential candidate Sen. Vicente Sotto III see a need for a “skills-matching” program to provide more employment opportunities to PWDs and the elderly.

Manila Mayor Isko Moreno, in 2019, signed a memorandum of agreement with fast food companies to employ PWDs and the elderly. For each branch, a minimum of two senior citizens and one PWD should be hired.

READ: How the Deaf deal: Finding work and working to be heard

TSB