Poll campaign draws focus on Mindanao’s ‘forgotten’ areas

BRIDGE OF HOPE Village watchman Musli Jumli stands guard on the newly constructed 500-meter bridge that links Marang-Marang Island to Isabela City’s mainland. Jumli, who used to swim across the sea to go to school, sees the bridge as a hope for their community’s future.—JULIE S. ALIPALA

ZAMBOANGA CITY, Zamboanga del Sur, Philippines — Close to 40,000 people, about half youngsters, were drawn to the Cesar Cortes Climaco Freedom Park in Barangay Pasonanca here on March 17 for the grand rally of presidential hopeful and Vice President Leni Robredo, dubbed as “Layag (Sail) Leni.”

But most of them may not have an idea of the historical significance of the place, until after they were there.

Before introducing the vice president, Mayor Ma. Isabelle Climaco Salazar reminded everybody that they were on hallowed ground as the park, which used to be called Abong-Abong, was renamed after the city’s former mayor who made his mark as a freedom fighter.

Salazar, who is Climaco’s niece, refreshed for her audience a historical tidbit of the late mayor fighting alongside the late Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. against the dictatorship which cost them their lives.

“They sacrificed their lives for our country; we must not forget their sacrifices,” she said.

Article continues after this advertisementSalazar then urged them to honor the memory of Climaco by making sure that their votes go to candidates who could be trusted to take care of the future of the country.

Article continues after this advertisementWestern Mindanao State University professor Edgar Araojo said the March 17 rally “is like bringing back our young generation to the place where our ancestors stood strong in fighting against the dictator, invasion, occupation and conquerors.”

Historical site

Apart from the Climaco Park, Pasonanca also hosts the Pulungbato or Columbato, which means a column of rock, a historical site that used to be the seat of government of the Subanon tribe which ruled this part of the country before the Spanish occupation.

Although marked by episodes of battle over territory, trade also defined the relations between the Subanon tribe and the Sulu and Maguindanao sultanates which used to rule large parts of Mindanao.

The Pulungbato-Abong-Abong stretch covers close to 32 hectares, according to city assessor Erwin Bernardo.

In the mountainous and rocky terrain, “our ancestors planned their attacks against foreign invaders,” said Araojo.

During World War II, the place was a major holdout for Japanese forces. In 1945, toward the tailend of the war, it became the scene of fierce battle for control of the city, featuring constant aerial bombardments.

As a result, an estimated 6,400 Japanese and 220 American soldiers were killed, many of them buried there. Some 665 American soldiers were also wounded. A memorial was built in their honor, marked by a giant combat helmet.

In 1983, then-Mayor Climaco erected a freedom wall at Abong-Abong to honor Aquino, whose assassination would spark widespread dissent against the dictatorship leading to its toppling in 1986.

On Nov. 14, 1984, Climaco was gunned down at Buenavista–La Purisima Streets while helping firefighters put out a fire. A week later, some 200,000 people came for his burial near the grounds of the World War II memorial.

Remote communities

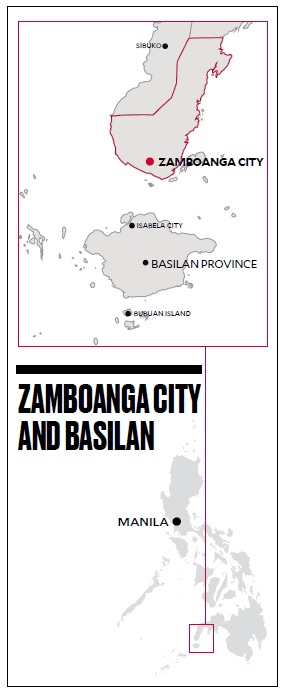

The national campaign also trained the spotlight on the seemingly forgotten province of Basilan.

When Robredo held her campaign rally in Isabela City, Basilan, on March 16, she became the second presidential candidate to campaign in the province during the post-1986 elections. The first was Sen. Jovito Salonga who ran for president in 1992 under the Liberal Party, with Sen. Aquilino Pimentel Jr., a son of Mindanao, as his running mate.

Ecstatic over the historic attention from major national politicians, some 45,000 people flocked to the rally and accorded the vice president a rockstar welcome.

The following morning, Robredo took a 20-minute ride on a motorized banca towards the mangrove-covered island village of Marang-Marang to talk to a gathering of women of the Sama Bangingi, Tausug, Badjao and Yakan indigenous groups.

“Even COVID-19 cannot easily penetrate our island, which has been covered and protected by mangroves,” said Nacida Angko, 33, a single parent of two children. “No one got sick here, not even our elders, because we always got the sun and the sea for everyone.”

WARM RECEPTION Residents of remote Barangay Marang- Marang in Isabela City, Basilan, await the arrival of Vice President Leni Robredo on March 17. Robredo took a side trip from her campaign sortie in the province to meet women leaders in the village. —PHOTO COURTESY OF THE OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT MEDIA BUREAU

Claudio Ramos II, the city tourism officer of Isabela, described Marang-Marang as a village of 2,097 people, surrounded and protected by mangroves and accessible by small vessels like motorboats. Women make up almost half of the people in the area, where fishing, gathering clams, shrimps, squid and other aquatic resources, as well as mat weaving, are main sources of livelihood.

Janang described her community as a fishing village, where men go fishing in the morning while the women earn extra income by preparing homecooked native delicacies to guests in a nearby floating cottages.

She also described the 1,000-ha island as isolated from the town center, where some houses were on stilts.

Access to mainland

It was only in 2021 when the construction of the P10.21-million concrete bridge was finished that the island was finally connected to Malamawi village on Basilan’s mainland, she added.

“We witnessed the difficulties of villagers here, especially among students going to school,” said Deputy Speaker Mujiv Hataman, who initiated the project.

Musli Jumli, 53, head of barangay tanod (village guards), called the 500-meter concrete bridge as “bridge of hope” for easing travel to mainland Basilan for the more than 2,000 villagers who live in Marang-Marang.

“Before, we used to swim to go to school,” Jumli said. “We had to swim to cross the sea from our island and reach the mainland. We swim towards mangrove areas, where we had to walk through 200 meters of mangroves before reaching Malamawi. There, we start dressing up for school, it’s another trek to school,” Jumli told the Inquirer.

He said the community got used to swimming every day because they had to. “Everyone here is a swimmer (because) if you can’t swim, you cannot see the nearest village or attend classes there,” he added.

MEMORIAL The grave of the late Zamboanga City Mayor Cesar Climaco in Abong- Abong, Barangay Pasonanca, has become a memorial to the heroism of the man who fought the Marcos dictatorship until his death in 1984. It has become a part of the important sites that dignitaries visit in the city so they can pay tribute to Climaco’s causes and struggles. —JULIE S. ALIPALA

Jumli said four of his six children experienced the ordeal that he and his wife went through. “But at least, my two youngest children are now enjoying this bridge. They still have to swim to harvest food in the mangrove, though,” he added.

Along the bridge are huge water pipes bringing potable water to the village.

“We used to buy water from the mainland,” said Jumli. “It was costly and heavy. Now, we have a faucet and tap water. The villagers need not pay that much to go to school, go to the market and to buy water. I see more people buying bicycles and motorbikes. These things were impossible years ago,” Jumli said.

“Now, I don’t have to worry about my two daughters crossing the water. I have more time to focus on my little sari-sari (variety) store here,” said Angko.

Hataman said they made sure to complete the bridge during the pandemic so that when in-person classes start, the children no longer had to swim to go to school. The bridge is also expected to spur economic activities as fishermen and their families can now easily deliver fresh catch to the market in Malamawi.

With the elections a little over a month away, Hataman is hoping that the country’s next leaders will see the plight of these seemingly unseen people.

RELATED STORY

‘Pink’ crowd defy rain for Robredo grand rally in Zamboanga City

That day when Basilan’s ‘isolated’ island village welcomed banca-riding Robredo

Basilan all set for Leni-Kiko rally; organizers expect 40,000